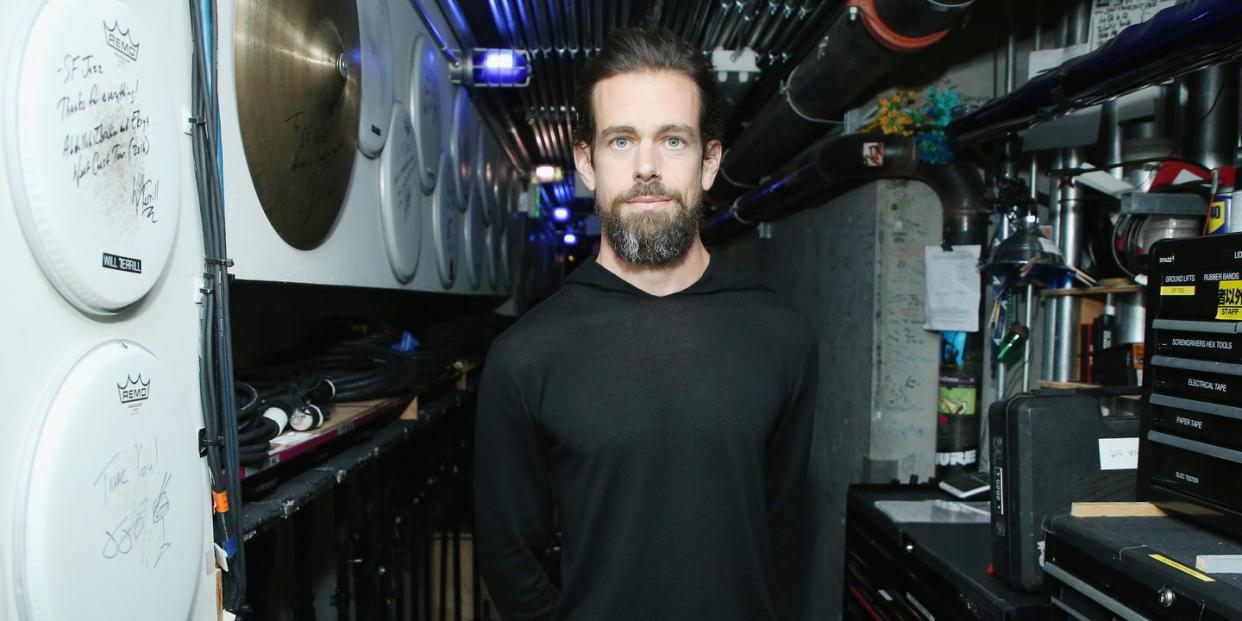

For Jack Dorsey, It's Biohacking. For Women, It's Often an Eating Disorder.

When Jack Dorsey, the CEO of Twitter started fasting through the weekend, he felt like he was “hallucinating.” “Time really slowed down,” he told CNBC. In the hours between his five weekly meals, he says, “You have this very focused point of mind in terms of this drive.”

When Phil Libin, the CEO of an artificial intelligence studio, fasts, he feels a “mild euphoria.” “I’m in a much better mood, my focus is better, and there’s a constant supply of energy,” he told the Guardian.

Kevin Rose, the founder of Digg, launched an app called Zero, to help intermittent fasters track how many hours per day they go without eating.

It’s interesting to watch Silicon Valley discover, under the guise of biohacking, what so many teenage girls know. Kate Moss didn’t say nothing tastes as good as skinny looks. Looking skinny obviously comes with societal perks, but for people who go to great lengths to look that way, the perks are often rivaled by the feeling-the mood-altering effects of skipping meals. Many women express skepticism when Silicon Valley entrepreneurs espouse intermittent fasting, which is hardly surprising: Fasting evangelists sound straight out of the early chapters of an eating disorder memoir. In her 1998 book Wasted, Marya Hornbacher described her heady early days of self-starvation as a freshman at the competitive arts high school Interlochen. “At first, everything tastes and smells intense, tactile experience is intense, your own drive and energy themselves are intense and focused,” she wrote. “Your sense of power is very, very intense.” (Later in the same chapter, Hornbacher was hospitalized after collapsing at prom.) You can find similar accounts of food restriction and euphoria in books about men-competitive wrestlers, jockeys, and POWs in particular.

Hornbacher wrote that the feeling of power derived from deprivation was addictive, and twenty years later, science routinely backs her up. Neuroscience research has shown that anorexia and drug dependence suppress appetite through the same “signal foul-up.” Studies by Valerie Compan, PhD, a professor of neuroscience at France’s University of Nimes have shown similarities between anorexia and ecstasy use. “Restrictive food intake may have an antidepressant action in stressful contexts,” Compan says. For some people, she explains, the neurological mechanisms meant to limit the “reward value” of fasting can become “chronically disorganized.” At some point, in other words, the feeling of relief you get from not eating motivates you more than food, even after you’ve plunged below your goal weight. Meanwhile, the obsessive thinking and physical weakness of anorexia unravels any mental clarity or energy that might be found in the early days of fasting.

This is not to say that everyone who dabbles in intermittent fasting will develop an eating disorder. According to Christina Wieringa, Ph.D., a psychiatry professor at UCSD’s Eating Disorders Treatment and Research Center, eating disorders reflect a perfect storm of genetics, stress, and certain hormonal and neurodevelopmental changes associated with puberty and weight loss (whether intentional or unintentional). “In people that have a biological or a genetic predisposition to developing an eating disorder, fasting can be [the eating disorder] trigger,” she says. “And then what tends to happen is that it becomes reinforcing. There’s some benefit that people feel from weight loss or dieting that then serves to maintain the behavior.” Wieringa’s research has shown that, for people with a history of anorexia, a 16-hour fast will decrease their sensitivity to hunger and other reward mechanisms, like money.

To experienced dieters, the term “intermittent fasting” might be new, but the concept likely isn’t. I first read about skipping meals daily in New Yorker writers Susan Orlean and Patricia Marx’s refreshingly honest but deeply outdated (and out-of-print) 1999 book The Skinny. In it, smart, successful, progressive women copped to how much they think about dieting, and shared their weird, often unhealthy diet tricks. The woman who admitted to never eating before 3 p.m. didn’t call it intermittent fasting; it was just a rule. I don’t abide by that rule, but I see where she and Dorsey are coming from. I too find I am most thoughtful on the rare day when I blow through breakfast and lunch hours with appetite-suppressing coffee. I feel lighter and more alert, like I just got out of a pool (and later, very hungry). Thousands of years of religious fasting attest to its effects.

When I was a teenager, I was warned that the good feeling self-starvation can cause is the result of an outdated evolutionary mechanism. Our hunter-gatherer brains release happy chemicals so we don’t panic while we find our next meal-a claim I see all the time in writing promoting intermittent fasting. “In Paleolithic times, we needed all our mental faculties and keen senses to find food, when food was scarce, our alertness and mental focus naturally increased,” says bestseller The Complete Guide to Fasting. And there may be some truth to that idea, according to Compan. Her research suggests that “identical molecular networks in the [brain] trigger a rewarding effect of anorexia and increase motor reactivity.” Other research suggests that calorie restriction or a fasting diet can promote longevity.

But for people who are mostly motivated by personal appearance and productivity, intermittent fasting seems to promise to let you have it both ways: to harness the euphoric highs of self-starvation (and maybe the slimming effects of calorie restriction) without developing an eating disorder-a ridiculously alluring possibility. Just like some people can use drugs without being addicted, Compan says, some individuals might be able to severely restrict their diets without developing anorexia. She warns that fasting might be more risky for adolescents and women, whose higher rate of eating disorders is shown to be related to ovarian hormones. Then there is the fact that most of the research about eating disorders involves people who already meet the diagnostic criteria for eating disorders. “There’s lots of people who live with sub-diagnostic eating disorders,” Wierenga adds, “and it would not be good for them to engage with intermittent fasting.”

Silicon Valley fetishizes the neurochemistry of brain-hacking, but there are social aspects to dieting, and when it becomes disordered eating. It’s probably easier to safely fast if Kate Moss-thin isn’t your physical ideal, reinforced in endless Instagram posts. It’s also probably easier to have a functional, sub-diagnostic eating disorder if you don’t need to meal plan for yourself or your family, and if you don’t derive self-worth from doing so. If you can can sit down at the end of a long, fasting day and order a restaurant steak salad instead of, say, walking around the grocery store in a daze, debilitated by the difference in net carbs in among brands of whole wheat pasta, only to end up ordering a pizza and feeling bad about it the next day.

Still, what’s most bizarre to me about Silicon Valley fad diets is that women I know have tried-and discarded-all of them. The first was Soylent, a meal replacement shake that failed our mothers in the 1990s-it was then known as SlimFast. Then there is intermittent fasting. Whether or not skipping breakfast and lunch becomes a full-fledged eating disorder, it can be painfully antisocial. Most of the women I know who once regularly skipped meals stopped because the social and emotional benefits of eating with other people-classmates, coworkers, dates, friends and family-outweighed the benefits of calorie restriction. Many of these women moved from calorie restriction to protein-heavy, low-carb diets long before Silicon Valley was talking about Paleo and Keto. (In the early 2000s, it was called the South Beach Diet.) But these too seem to be waning in popularity. Eating enough protein to eliminate hunger-related mood swings gets expensive, and reasonable minds disagree about how much meat is healthy to eat, or how many chickpeas and hard-boiled eggs one can stand to eat.

In most of the conversations I have about diets with women lately, ethical considerations about the environment and food systems provide an urgent counterbalance to decades-old concerns about goal weights and mood swings. People talk about eating plans like the six-day vegetarianism Edith Zimmerman has written about in The Cut. Eating in an environmentally mindful way isn’t easy or inexpensive. (Plus, Wieringa points out that eating disorders don’t care about intention, any eating plan can become a fixation.) But, personally speaking, it sounds like a great relief to have an organizing principle outside of my own appearance and productivity. A planetary diet doesn’t square with the self-interest and perpetually optimizing individualism of Silicon Valley. But if the tech industry stays two steps behind women who think about food-and if tech bros keep dabbling in “ego-dissolving” drugs like LSD and mushrooms-it could catch on.

('You Might Also Like',)