I've Spent Months Fighting Coronavirus in the ER. Police Violence Is What Really Scares Me

I’m an emergency medicine physician in New York City—one of the only Black physicians in the entire emergency department at my hospital. While many New Yorkers followed shelter-in-place orders, I’ve been called to work to help heal the people afflicted by the coronavirus pandemic. I drive to work, and lately, compared to typical New York City traffic, the roads are empty. You might think this was a relief for me, but it was the opposite. I may have a shorter commute, but I’m a Black man behind the wheel when law enforcement and the government have ordered us to stay home. Stay-at-home rules have been enforced much more harshly against Black people, and I am aware that I am very much a moving target.

This is a feeling that I’ve dealt with my entire life. When I was growing up, toy guns were never toys. Water guns weren’t even a thing in my home. My mother wouldn’t allow sling shots. And even if I made the figure of a gun with my hand, she would slap me so hard I would forget what I was even doing. Why does she care about this so much? I’d wonder, rubbing the pain out of the back of my head. I didn’t even bother to try and figure it out; adults had weird rules that we kids didn’t get.

By the time I was a teenager, it started to come into relief. I started to realize that I was no longer “cute”—that my presence was being interpreted differently by the people around me, be it classmates, teachers, or parents of my friends. It was intangible, but it was also heavy. It followed me like a shadow, but when I turned around to confront it, I couldn’t see it for what it was. So I ignored it.

Until I learned how to drive. When you learned to drive, maybe you learned about parallel parking, yielding and merging. When a Black mother teaches her son how to drive, there are more important lessons that come first. Eyes on the road. Hands on the wheel. Don’t move one thing. Say, “yes sir.” My first lesson of driving was about how to behave when I get pulled over. But before that, my mom would beg: “Please don’t get pulled over, please.” I started to see her pleas for what they were. I realized when they pulled me over, they wouldn’t see me the way my mother saw me. They would see something else.

So I heeded my mother’s warnings. I do everything I can to look “essential.” I do not change out of my scrubs after work—even though it means potentially contaminating my car with the coronavirus, or bringing it into my home, where my partner sleeps. I keep my white coat on, because I know it signals authority and respectability. I pin my doctor’s badge to the top of my sleeve facing the driver’s window, so I won’t have to search around and risk being shot when the officer asks for ID. I place my essential information on my dashboard, so I can slowly and cautiously reach for it without being interpreted as suspicious. I rehearse my tone of voice, the ease with which I speak, so I can calm their inevitable racism.

As I write this, I am mentally preparing myself for work today. Well, not work really—more like, the drive home from work. Even in the midst of a pandemic, the actual work is the easy part. I have trained under some of the most prestigious emergency doctors in the world, in a level one trauma center that requires knowledge about everything from diabetes to heart attacks to gunshot wounds. Now, I have led teams through the worst of the pandemic. I can do this part.

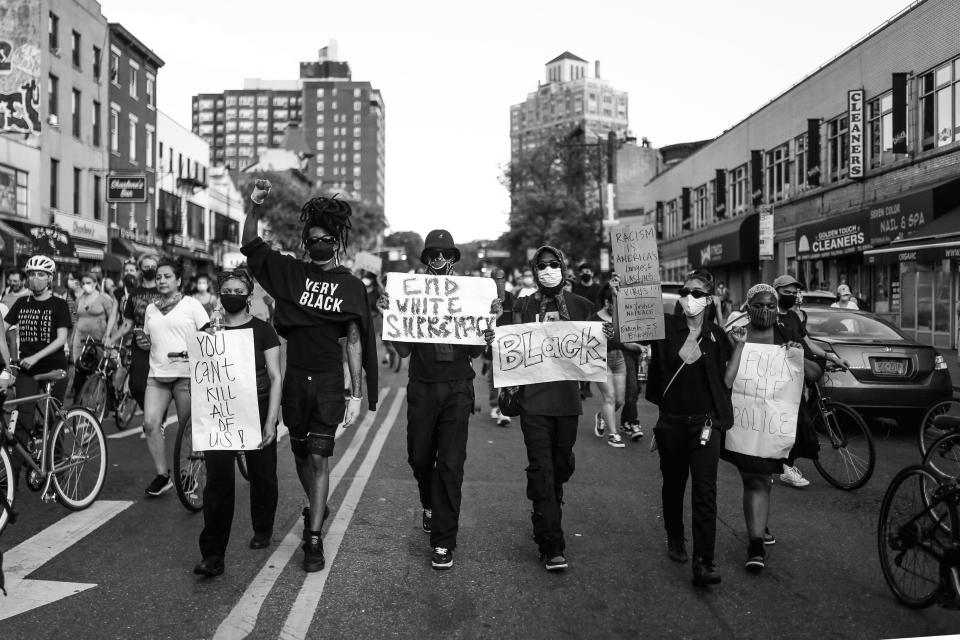

It’s the drive home that I’m preparing for. New York City was under a curfew, presumably to curb the impacts of demonstrations, filled with tens of thousands of people marching for Black Lives. For my life. The curfew terrified me, not just because I know it cloaks further police brutality by making it harder to see and record. It also terrifies me for my patients, many of whom are Black and homeless. They not only have to fight the current pandemic, which has killed Black people at a wildly disproportionate rate, but also the much more insidious pandemic of racism.

But I’m also terrified for my own safety. I’m an ER doctor operating on a 24-hour schedule, driving to and from work at all times of the day. Tomorrow’s shift starts at 4pm and ends at midnight, which means I will be on the road around 1 in the morning. How will I look to them, with their batons and their riot gear? What will happen to me? And more importantly, how do I even explain any of this to the people I work with, who can passively ignore my scheduled shift even after reading the news and making their own pledges of anti-racism via black squares on Instagram?

Maybe when I get in the car, I’ll make sure to use cruise control to be sure I won’t accidentally speed. Maybe that will prevent any chance of being pulled over. Maybe I will call my fiancé for the drive home, so anything that happens can be recorded. Maybe I will share my location the entire time with my twin brother, who’s also a doctor in New York. Even though it’s a pandemic, I will ditch my face mask while I drive home—just so I don’t look suspicious to the officers. I’d rather get COVID-19 than die of their brutality. I’ve already rehearsed it: if they move to put a knee on my neck, I would try to scream, “I’m a doctor,” before I lose consciousness. Maybe these things will keep me safe.

Of course, as you’ve already seen this year, they won’t. Breonna Taylor was an essential healthcare worker, like me. She was killed by the police for—what, exactly? Being in the wrong home? There was nothing George Floyd could have done to “be better” when Derek Chauvin was kneeling on his neck. This is to say nothing of the countless Black transgender people who are killed every year and whose names rarely echo through our streets with the same vigor. They should not have to somehow earn their safety.

I answered a phone call from my mother this morning. It is a miracle that she ever sleeps, given all the worrying she has to do for her three Black sons. I remember rolling my eyes at her, telling her to calm down, but of course, I was simply too afraid to confront the fact that she was right. I’m a 32-year-old man, and my mother still asks for my work schedule. She does so as calmly as she can, knowing that if she expresses fear, she may upset me. Today, she called me to gently repeat the same instructions she gave me when I was 16 and newly behind the wheel. She tells me to take care of myself, and then makes a joke so she can hear my laughter. I tell her not to worry, but I know now more than ever, that this is pointless. So instead, I tell her that I love her—just in case these are the last words she’ll ever hear from me.

For Saeed Jones, generations collapse into seconds during an American week of chaos and sorrow.

Originally Appeared on GQ