Italy's Secret Wine Scene Is Hidden Amid the Cliffs of Cinque Terre

To find out more, I embarked on six days of tastings, cellar visits, and vineyard hikes.

From left: Francesco Lastrucci; Andrea Leonardini/Courtesy of Cheo

From left: Aperitivo hour at A Pié de Ma bar, in Riomaggiore, Italy; the terraced vines of Cheo winery overlook the town of Vernazza.It was early morning on the footpath to Corniglia, and half an hour in, I’d seen more farmers than hikers. Three of them tended to their cliffside vines as I passed by. One was spraying his leaves; another was clearing the scrub around his tiny vineyard; the third rode a toy-size train, called a trenino, on a rail up the steeply terraced cliffside.

For more than 20 years, Cinque Terre has been one of Italy’s most popular places to visit. Along a 10-mile stretch running north up the Ligurian coastline, five villages — Riomaggiore, Manarola, Corniglia, Vernazza, and Monterosso — are wedged between cliffs and sea, their pastel-colored houses stacked up the slopes. The impossible prettiness of it all draws travelers from across the globe.

But above them lies another Cinque Terre, one built on agriculture. For a thousand years, locals have tamed the cliffs by terracing them with stone walls from top to bottom. Their crop: wine, so fine the poet Dante sang its praises and medieval kings and popes guzzled it by the flagon. In the 20th century, however, a combination of emigration, plant disease, and mechanization (these craggy plots can only be worked by hand) decimated Cinque Terre’s wine industry. Since the 1970s, 90 percent of the acreage once used for viticulture has been abandoned; the terraces that once braided the coastline have, in many places, been swallowed up by scrub.

Only a few vintners remain, but today, these holdouts are making some of Italy’s most distinctive wines. Cinque Terre is known for its intensely mineral, saline whites, usually made from bosco, albarola, and vermentino grapes — a blend that’s officially recognized as a Denominazione di Origine Controllata (DOC) product. I wanted to explore Cinque Terre through its wine, so I embarked on six days of tastings, cellar visits, and vineyard hikes.

Uta Theile

Local wine on the terrace of Cantina Capellini, in Volastra.That morning on the footpath to Corniglia, I was looking for Adelaide, a century-old vine of dark Vermentino Nero grapes grown on the Cantina Capellini vineyard. I had learned about it the day before from local Edoardo Lanzi. “Vines are like our kids,” he had told me, stroking a leafy tendril.

Out on the cliff, I looked up. There it was: a vast, wild vine on the terrace above, its tree-trunk arms flexed like tentacles. Vines of red grapes, like Adelaide, were once scattered between the whites to keep the vines diverse and healthy, Laura Ampollini told me later. She runs the winery’s open-air Agrivino “tasting room” — a patch of dirt between two rows of vines.

Her husband, Mirco, is the seventh-generation winemaker at Cantina Capellini. Together, they opened the Agrivino in 2020. “We wanted to bring people into the vineyard, to smell the plants and feel the breeze,” she said. “We want to share the history — we have a thousand years of it.”

I continued climbing, past hikers sipping Cinque Terre DOC grown just feet away. Below me, the vines spilled toward the Ligurian Sea, the town of Corniglia clung to the cliff, and boats glided in the bay. It felt like I was dangling from a cloud.

Wine, I was starting to realize, was a portal to the real Cinque Terre. At the wine shop Ghemé, in Riomaggiore, owners Chiara Gasparini and Laura Ricci chatted as they pulled bottles off the shelves, pouring me a glug of each. I picked out my favorites at the bar A Pié de Ma, a five-minute walk away, where manager Barbara Boselli poured me a couple of ice-cool, flinty whites.

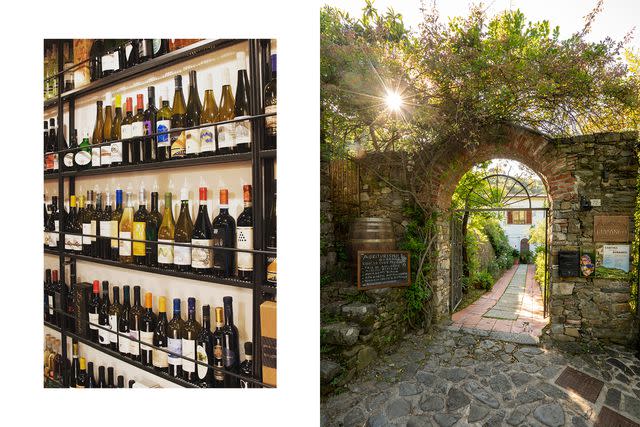

From left: Courtesy of Ghemé; Courtesy of Buranco

From left: Stocked shelves at Ghemé, in Riomaggiore; the entrance to Buranco.In the hilltop village of Groppo, I visited Cantina Cinque Terre, a cooperative founded in 1973 to help preserve local wine making. Some members are in their eighties: “Take away their vineyard and you take their life,” smiled my server, Martina Andriani, as she poured me a glass of vigne alte, which is made with grapes grown higher on the slopes.

But I didn’t just want to drink; I wanted to experience for myself why Italians dub this grueling trade “heroic viticulture.” At Buranco, a farm stay in Monterosso, I tried “wine-trekking”: hiking with a bottle in hand. Clambering around the terraces in the blistering heat, I gained an intense appreciation for the vintners’ work.

The next day I headed to Cian du Giorgi Winery, in the hamlet of San Bernardino. In 2017, owners Riccardo Giorgi and Adeline Maillard were working in Bordeaux when they came to Cinque Terre on vacation and stumbled on a semi-ruined vineyard. “I couldn’t stop thinking about it,” Giorgi told me on the terrace as we drank biodynamic rosé brighter than a highlighter pen. The following year, they moved there.

Giorgi stuffed a bottle of white into a backpack and drove us to a cliff looming behind Riomaggiore. “Usually I like to make people hike up, so they can feel the effort,” he grinned. Happily we took a trenino, which remains the only technology used in Cinque Terre’s vineyards. We cruised up 1,640 feet to the vines — some 90 years old, their arms twisted into sun salutations — and shared a toast as a rainbow arced overhead.

On my last day, the town of Vernazza was choked with visitors, but on its outskirts, Bartolomeo Lercari was calmly pouring organic wine on the terrace overlooking his hilly property, Cheo.

“My family has made wine here for five hundred years,” he said, lining up bottles: three whites, a red, and a sweet sciacchetrà. Later, we walked on land so steep that, as Lercari taught me how to recognize the vines — vermentino has soft leaves, bosco’s are harder and shinier — I dug my toes into the earth to stay upright. Below us, Vernazza sat astride its promontory, thrusting out into the sea. Music floated up on the breeze; crowds pushed through the streets. Thanks to the wine, I was high above it all.

A version of this story first appeared in the October 2023 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Cliff Notes."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.