Some of Italy’s Most Important Food Towns Were Devastated by Earthquakes — but the Local Food Scene Is Thriving

The best way to support the recovery? Booking a trip and ordering second helpings.

Francesco Lastrucci

From left: The hill town of Santo Stefano di Sessanio, in Italy's Abruzzo region; pasta all'amatriciana at Ma-trù restaurant, in Amatrice village.Natalia Nurzia stirred her thick caffè al torrone, a shot of espresso with milk and molten nougat, as we sat in her family’s bar in L’Aquila, the capital of the Abruzzo region. “We’ve been here since 1835,” she said, gazing across the square. “Not even wars, not even earthquakes could move us.”

For generations, Nurzia’s family has made chocolate torrone — the most popular version is softened by honey, swirled with cocoa, and mixed with hazelnut chunks to give an extra crunch — at Fratelli Nurzia. They were there on April 6, 2009, when L’Aquila was hit by an earthquake that killed 309 people and injured more than 1,600. It was one of several once-in-a-lifetime quakes to rock central Italy in the course of a decade. In August 2016, the town of Amatrice, in neighboring Lazio, was razed to the ground. Two months later, it was the turn of Norcia, a medieval walled town in Umbria famous for its churches and its food.

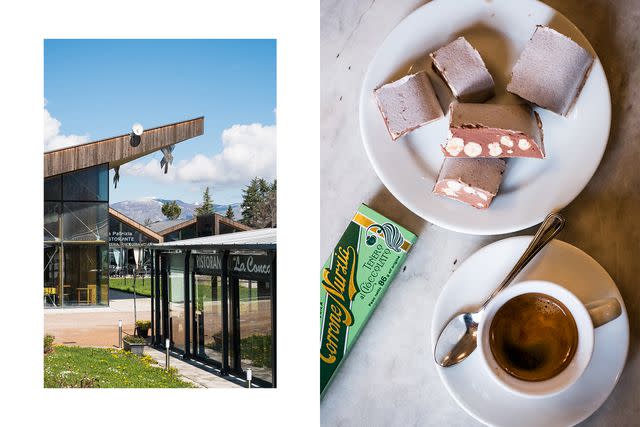

Francesco Lastrucci

From left: In Amatrice, the Piazza del Gusto Tradizione e Solidarietà houses eight displaced restaurants; torrone and espresso at Fratelli Nurzia.Central Italy has long been known as one of the country’s gastronomic havens. Before the earthquakes, as tourists flocked to Rome to eat pasta all’amatriciana, Romans drove to Amatrice to eat the dish in its hometown. While foreigners dreamed of Parma’s prosciutto, Umbrians knew the hams of Norcia, so good that the town gave Italy the word norcino — someone who cures meat. The area around L’Aquila, at the foot of the mountainous Gran Sasso National Park, was known for hearty, energy-spiking cuisine — including that nougat. It still is.

Cranes now dot the skylines, but these paesi terremotati, “earthquaked towns,” are rebuilding from the kitchen up. Last fall, I left the crowds in my home city of Venice for a road trip through the region: five days of wild landscapes and some of Italy’s most emblematic food, to witness how tourism is helping heal the area’s wounds.

Francesco Lastrucci

From left: Ongoing reconstruction at a church in Amatrice's old town; apple juice from Casale Nibbi, an apple farm west of Amatrice.Nurzia put it best. “L’Aquila can only restart with tourism,” she said, gesturing to the scaffolded buildings around the square, which once housed the offices whose workers kept her bar full. Construction is slow. “We need people to love it, to come on vacation.” And eat, she implied but didn’t say, because she was taking another sip.

Down the street from Fratelli Nurzia I found the deli La Camoscina, where Vito Laterza stood behind a counter piled with wheels of cheese. He thrust a chunk of firm, mountain-churned ricotta at me, explaining how shepherds light juniper berries to smoke the cheese, then top it with saffron. I bought some, as well as a bottle of genziana — a liqueur made from the root of the gentian flower, grown in the national park — and Vito’s own “fearsome” (his word) wine. “There are only two times to drink it: alone and with company,” he grinned.

Francesco Lastrucci

From left: Trout crude with scallops and apple-and-fennel sorbet at Vespasia, in Norcia; Vito Laterza displays pecorino canestrato cheese at La Camoscina, his deli in L'Aquila.Twenty miles east of L’Aquila is Santo Stefano di Sessanio, a medieval village folded into the mountains. Once known for its shepherds — the village was owned by the Medicis, who processed and sold the highly prized wool in Florence — today it’s home to Sextantio, an albergo diffuso (“scattered hotel”) with rustic rooms inside the village’s abandoned homes.

At the hotel’s restaurant, Locanda Sotto gli Archi, the menu is filled with old-fashioned working-class dishes. I tried a ravioli the size of my palm, stuffed with ricotta and swimming in saffron sauce. I ate pork neck drenched in sweet figs, and panzanella: a squidgy mix of bread crumbs, onions, santoreggia (a local herb), and tomatoes so sweet I thought they were candied.

Francesco Lastrucci

From left: The "Le Loggette" guest room at the Sextant hotel; dinner service at the hotel's Locanda Sotto gli Archi restaurant.The next day I drove up into the national park above Santo Stefano onto a plateau where a cowboy galloped after cattle across a wheat-colored plain, toothy gray peaks erupting in the background. Around whirligig bends, back into L’Aquila and heading north into Lazio, I reached the velvety, heather-hued mountains that gather Amatrice in a loose hug.

Or, what remains of Amatrice. Because the first thing you see is nothing. My eyes struggled to adjust to a solitary ruined bell tower, the only man-made structure remaining now that the rest of the rubble has been cleared. There are plans to rebuild the town, but seven years on, little progress has been made.

As I drove, the smell of bacon rushed through the window. It came from a field on the outskirts of town, where a clutch of chalet-style huts, designed by Stefano Boeri (the architect behind Milan’s Vertical Forest), forms a bastion against oblivion. Built with earthquake funds raised by the public, the square called the Piazza del Gusto, Tradizione e Solidarietà (Taste, Tradition and Solidarity) houses the eight remaining Amatrice restaurants, still cooking against the odds.

At Ristorante Ma-trù, Daniele Bonanni emerged from his kitchen. “This was one of the oldest restaurants in Amatrice,” he said, gesturing past chic scarlet chairs to a painting of his old digs, a trattoria on the main street. His mother ran it; he was her deputy. And on that day in 2016 he lost it all: his family, their home, their restaurant.

“I didn’t want to abandon Amatrice,” he said quietly. “My mother sacrificed herself for this place.” So he took the only things he could salvage from his home — his grandmother’s wardrobe, an antique bed warmer — put them in this hut, and started again.

Amatriciana is one of the simplest pasta sauces, and perhaps the most sublime. Daniele’s was majestic: the tomato warmed with pepper, the almost-charred chunks of guanciale (pork cheek), the blizzard of pecorino on top. The secret, he said, was using local products. He hesitated. “And the love you put into it.”

After lunch, Amelia Nibi was waiting for me with dessert. Her family runs Casale Nibbi, an organic dairy and apple farm in the hills 15 minutes west of Amatrice. She plied me with hunks of cheese, then plucked an apple off the ground as we walked through her orchards. “What kind is it?” I asked. She shrugged. “I dunno, an apple!” This is a place where the way you grow something is more important than what you grow.

On my last day, I wove around the mountainsides to Norcia, a destination for religious and culinary pilgrimages about an hour northwest of Amatrice. The medieval church of St. Benedict, which marked the birthplace of Europe’s patron saint, is being rebuilt after it collapsed in the 2016 quake; while other structures are still standing, they’re riven with cracks and unsafe to enter. Restaurants camp in prefab buildings outside the town walls.

Francesco Lastrucci

From left: A horse on the Pian Grande; lentil soup at La Campagnola, a restaurant in the village of Castellucio.First stop: Cantina 48, for bruschetta smeared with black truffles that grow on the mountainsides. Then, Palazzo Seneca, a gastro-hotel in a 16th-century palazzo. Run by the Bianconi family, it’s home to the Michelin-starred restaurant Vespasia, where, instead of Prosecco, I was handed a palate-cleansing genziana cocktail. My five-course vegetarian tasting menu included roasted celeriac with a sheep-milk cream and a poached egg with black truffle, wild mushrooms, and lentil broth.

Those lentils were grown on the Pian Grande, a yawning eight-square-mile plain wedged between rippling green mountains east of Norcia. Pulses have been cultivated here for centuries, and in summer, as the crops and wildflowers bloom, the meadows become a riotous patchwork: scarlet, blue, yellow, violet. As I drove through the region I also saw dozens of shades of green as new plants erupted from the earth.

Francesco Lastrucci

Outside Castellucio, nuns stroll through lentil fields interspersed with wild poppies.The village of Castelluccio, on a bluff overlooking the plain, was all but destroyed in 2016. While most of the rubble has been cleared, the town has yet to be rebuilt; most former residents live elsewhere and drive in to work. Yet Castelluccio was lively as Italians crammed into shacks to taste its famous lentil soup. I tried the dish at the bar La Campagnola: it was thick, almost meaty, drizzled in lurid green olive oil. Beside me, motorcyclists slurped down bowlfuls; opposite, at the produce stall Lu Soccio, an elderly couple debated the merits of the five types of chickpeas on offer. Nearby, I met farmer Vincenzo Bertoni, who was selling his homegrown pulses outside the tumbled-down house of a relative.

“Progress is slow, but we have to thank the tourists who never abandoned us,” he said, bagging up my lentils and roveja, a rare, nut-brown kind of pea. Only in Italy can food help whole communities recover from tragedy.

A version of this story first appeared in the July 2023 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "The Comeback Kitchens."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.