Issey Miyake, Man of the Beautiful People

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

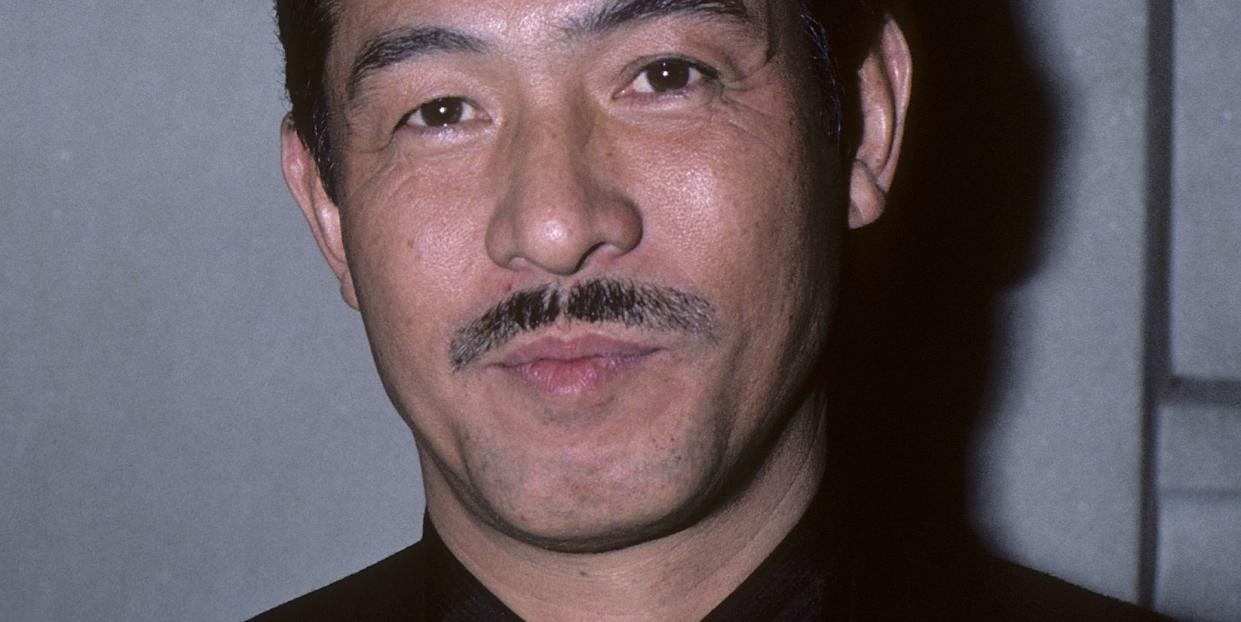

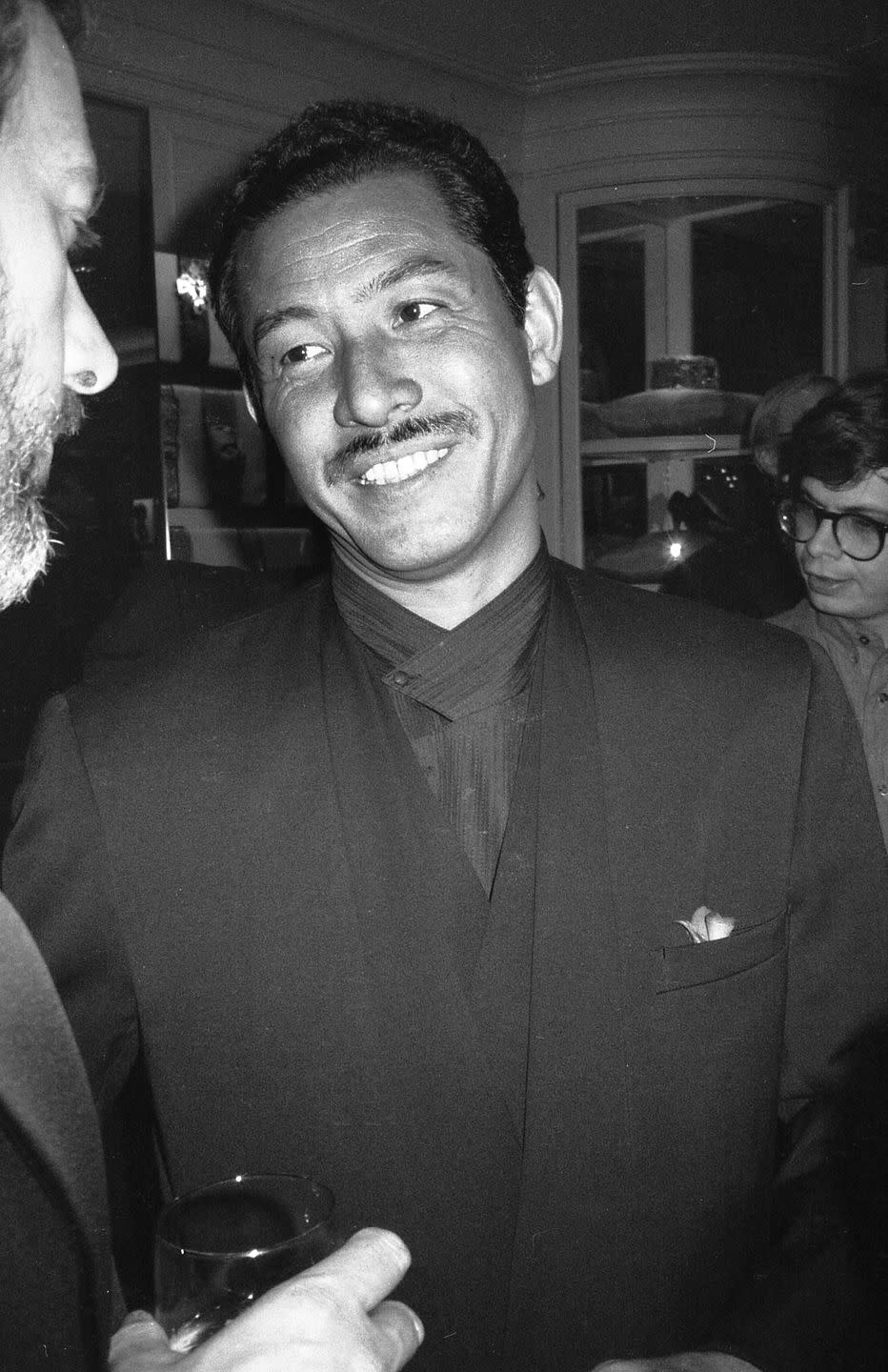

In a softly filmed 1985 interview, Issey Miyake smiles at a teacup that's handed to him partway through, admiring the artistry of a seemingly innocuous item. It was a remarkable moment. One: because Miyake was notoriously private, giving the press few opportunities to mine the man behind one of the world's most successful cult labels. And two: because the designer's uniform is nigh on identical to the one his brand espouses 37 years later. Look down any street in any city with comically high rents, and you'll several exact replicas, replete in a pleated, soft-shouldered blazer, matching trousers and, sometimes, a languid, liquid-like scarf. Such is the obligation for a card-carrying Miyakean.

According to morning reports by the Japanese media, the designer died on Friday at 84 after a battle with liver cancer. A private funeral has allegedly already taken place. Now, the fashion industry pays its public condolences. WWD magazine's Tianwei Zhang posted a photograph of a youthful Miyake on Instagram, anchored by the words "rest in peace." Vogue, 10 Magazine, and designer Jonathan Anderson all followed suit.

These are not just off-the-cuff responses in an age of digital performance. Miyake's death is a genuine loss to the fashion industry. He designed for the very people who admire design, who admire aesthetics—fashion people, art people, media people—and his label thus became the mandatory kit for such women and men. That's because Miyake made clothing that was guided by the principle of design, to his own "monozukuri" or his way of making things, rather than by the whims of fashion. When Japan hosted the World Design Conference in 1960, Miyake, then a 22-year-old student at Tama Art University, wrote a letter to the event organizers asking why clothing design was not included.

Upon graduation, the designer enjoyed stints working in Paris; first, for Guy Laroche, then Hubert de Givenchy. He lived in New York for several years after, before eventually moving back to Tokyo. Japan, high on the fumes of the World Exposition, was brimming with opportunity. Miyake seized it with both hands to found the Miyake Design Studio in 1970: a high end, high concept label in which the designer perfected his signature.

Back then, it was structural, origami-like, and abstract. Trousers were wide and billowing. Sleeves fell way past fingertips, and silhouettes ballooned in a sky of black, gray, and beige. The Issey Miyake we know today is simpler—a key principle of the designer's outlook—and most recognizable when comprised of precise pleats that give a fluid texture to wardrobe staples. These clothes have the versatility of wardrobe basics and yet refuse to blend in. Wear a quiet pair of black Miyake Pleats Please trousers, and everyone knows that they're Miyake Pleats Please trousers. (And it must be said, in a twist of coincidence, those pleats are perhaps more popular now than ever before, finding a new audience in the revisionist hype of Gen-Z style.)

Such brand recognition is, usually, only reserved for Miyake's louder contemporaries. But his precision is unique. So too is the late designer's background. Born in Hiroshima in 1938, Miyake witnessed firsthand the destruction of the city under American warplanes during World War II. Though he was hesitant to discuss this event—indeed, Miyake told The New York Times in a 2009 interview that he didn't want to be remembered as "the designer who survived the atomic bomb"—one could draw parallels between the experience of destruction and chaos at such an early age, and the satisfyingly ordered aesthetic which he cultivated in later life. Issey Miyake is a brand that feels like the fashion equivalent of crunching autumn leaves underfoot, or the inaugural squeeze of a fresh tube of toothpaste. It is soothing and comforting and elegant all at once—all attributes that led Steve Jobs to the designer, who, in turn, created the late Apple innovator's now famous turtleneck.

So unique it is, that Miyake's technique of "micropleating" (a process that involves wrapping fabrics in layered paper and heat-pressing them) changed the complexion and the character of polyester, a material once considered gauche. In the designer's stores, it became respectable, paving the way for other blue chip brands to involve a robust, hard-wearing textile in luxury fashion collections. "There are no boundaries for what can be fabric," Miyake once famously said.

Following the announcement of his death, the brand released a statement in tribute to its founder. "Never one to embrace trends, Miyake's dynamic spirit was driven by a relentless curiosity and desire to convey joy through the medium of design"—a curiosity that found magic in the mundane, that saw beauty in everyone and everything, whether that was a soft-shouldered blazer, a bolt of scorned polyester, or a white, forgettable, porcelain teacup.

You Might Also Like