Isaac Mizrahi’s New Memoir, I.M. , Is No Frockumentary—And the Better for It

Isaac Mizrahi’s New Memoir, I.M., Is No Frockumentary—And the Better for It

Isaac Mizrahi in Vogue

Isaac Mizrahi in Vogue

Isaac Mizrahi in Vogue

Isaac Mizrahi in Vogue

Isaac Mizrahi in Vogue

Isaac Mizrahi in Vogue

Isaac Mizrahi in Vogue

Isaac Mizrahi in Vogue

Isaac Mizrahi in Vogue

Isaac Mizrahi in Vogue

Isaac Mizrahi in Vogue

Isaac Mizrahi in Vogue

Isaac Mizrahi in Vogue

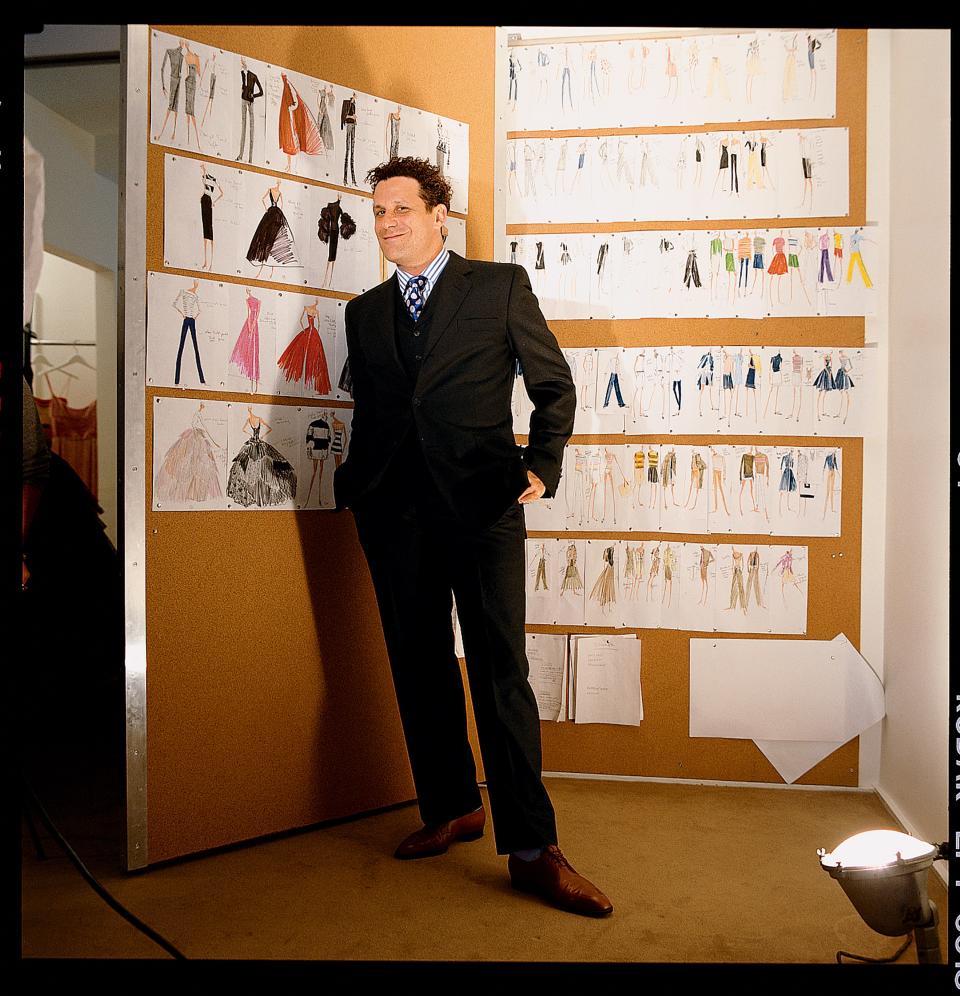

Fashion isn’t only about appearances, but it is an industry filled with “visual people,” and surfaces count for a lot. Few have understood that better than Isaac Mizrahi, who seemed to arrive fully formed on the scene in the late 1980s. He couldn’t have made a better first impression if he had tried. Here was a thoroughly New York designer—with the accent to prove it, a distinctive personal look (high-waisted pants and a mop of black curls often kept in check with a bandana), an encyclopedic grasp of (pop) culture, plus a seeming compulsion to speak in Vreeland-esque epigrams. And then there were the clothes. “What the world was missing,” writes Mizrahi looking back in time, “was American clothing with a real sense of humor. And color!”

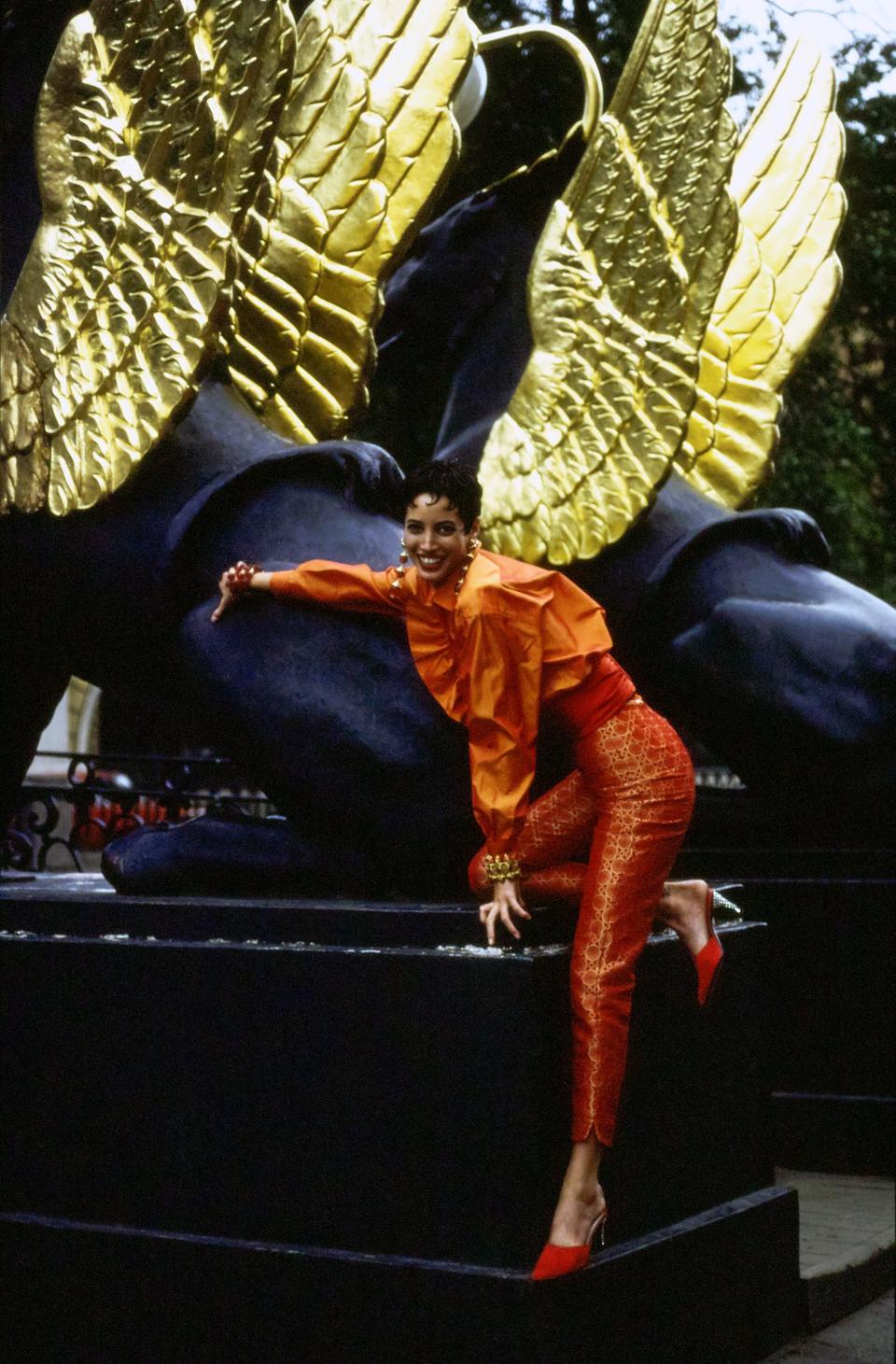

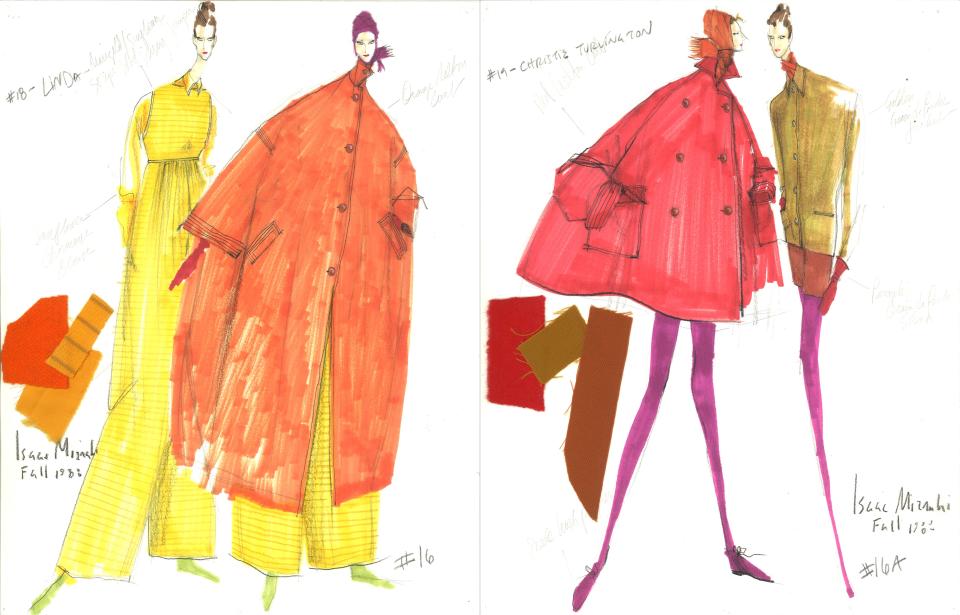

Isaac Mizrahi Fall 1988

(Left) Linda Evangelista’s jumpsuit and coat ensemble was dubbed “Orange Orange”—after the Kool-Aid flavor; Christy Turlington’s look (right), took its name from a character in Breakfast at Tiffany’s, “Sally Tomato.”

Mizrahi, who now has his own production company and keeps a toe in fashion, believes in clothes that work for women: “Solving problems,” he once told Vogue, “is why I am a designer.” That he had a particularly American approach to fashion should come as no surprise, seeing that he worked with such fashion patriots as Perry Ellis, Jeffrey Banks, and Calvin Klein before going solo. Although he was innovative and often ahead of his time, Mizrahi can’t accurately be described as an avant-garde designer; rather his specialty was rethinking classics in new shapes and/or luxury fabrications that communicated comfort rather than stiffness. Think of a luxurious cashmere shell paired with a taffeta ball skirt; side-stripe “sweatpants” for evening made of wildly expensive stuff; a swing coat in awning stripes . . . . Mizrahi’s designs are a reflection of himself: ebullient, upbeat, urbane, and always personal. His mother has been a constant source of inspiration, sartorial and otherwise. “It was drummed into my head that being smart trumped all else; wit and nerve were the most important elements of style; and money was not everything,” relates Mizrahi in his new memoir, I.M.

There’s plenty of fashion in this engaging read, but it’s no “frockumentary.” There aren’t even any pictures, which speaks to the strength of the writing and keeps the focus on Mizrahi’s voice and the content of his tale. I.M. is a coming of age/coming out story that challenges what you might think you know about Mizrahi, who has a very public persona, parts of which were exposed in Unzipped, the wonderful documentary that charts the making of Mizrahi’s Fall 1994 collection. The film culminates with a fashion show at which models tantalizingly change clothes behind a semi-sheer scrim, which is sort of a metaphor for Mizrahi’s longtime m.o. Revealing and concealing is something the designer knows a lot about; for much of his life, the reader learns, Mizrahi led a double life.

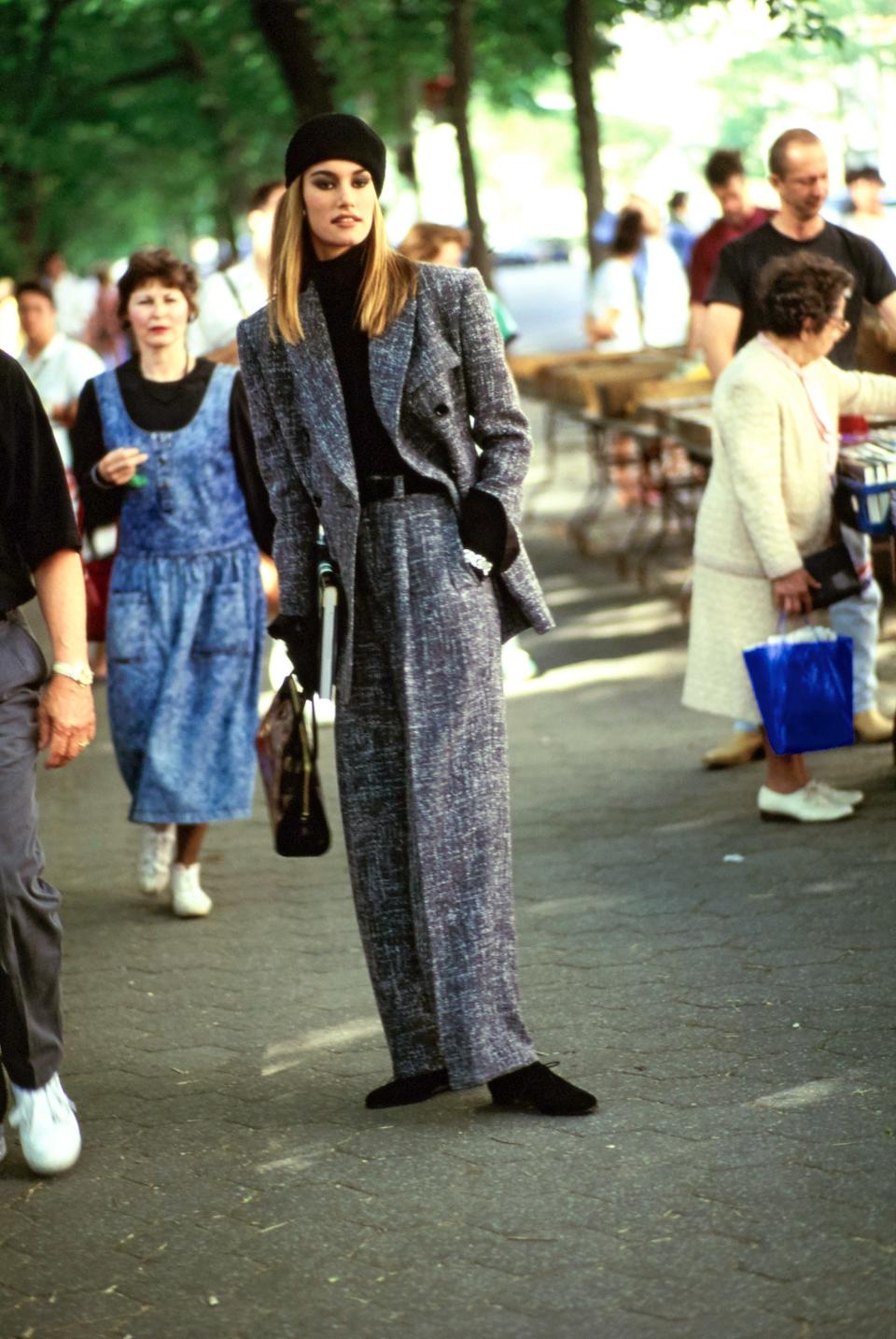

Claudia Schiffer in Isaac Mizrahi Ensemble, Vogue

Mizrahi never fit into a mold; for starters, he was the only son in a family of girls. Before he understood what homosexuality was, he felt different in a way he instinctively knew he should not express; even after coming out to his friends at Fiorello H. LaGuardia High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts (of Fame fame), writes Mizrahi, “revealing that I was a homosexual to [my family] felt like suicide.” In work, work, and more work, Mizrahi found an antidote to anxiety, if not happiness. Late in his garmento career, he was still “playing doubles”: “I yearned for a life in show business, but I was still hawking shmatas,” he writes. “A performer, a writer, trapped in the body of a fashion designer.”

In I.M. Mizrahi frees himself from the confines of his various personas—designer, performer, “fashion elf”—in a most engaging way. While there are plenty of LOL moments (some thanks to tales from the Sex Line, which Mizrahi clarifies, “was a telephone precursor to Grindr”), but there’s no sense of the performing seal here, or what Candace Bushnell once described in Vogue as Isaac’s “shtick.” Mizrahi has depth, and the broad range of his references supports his mother’s claim that the designer “has very definite ideas about everything, not just fashion. Fashion is just the tip of the iceberg.”

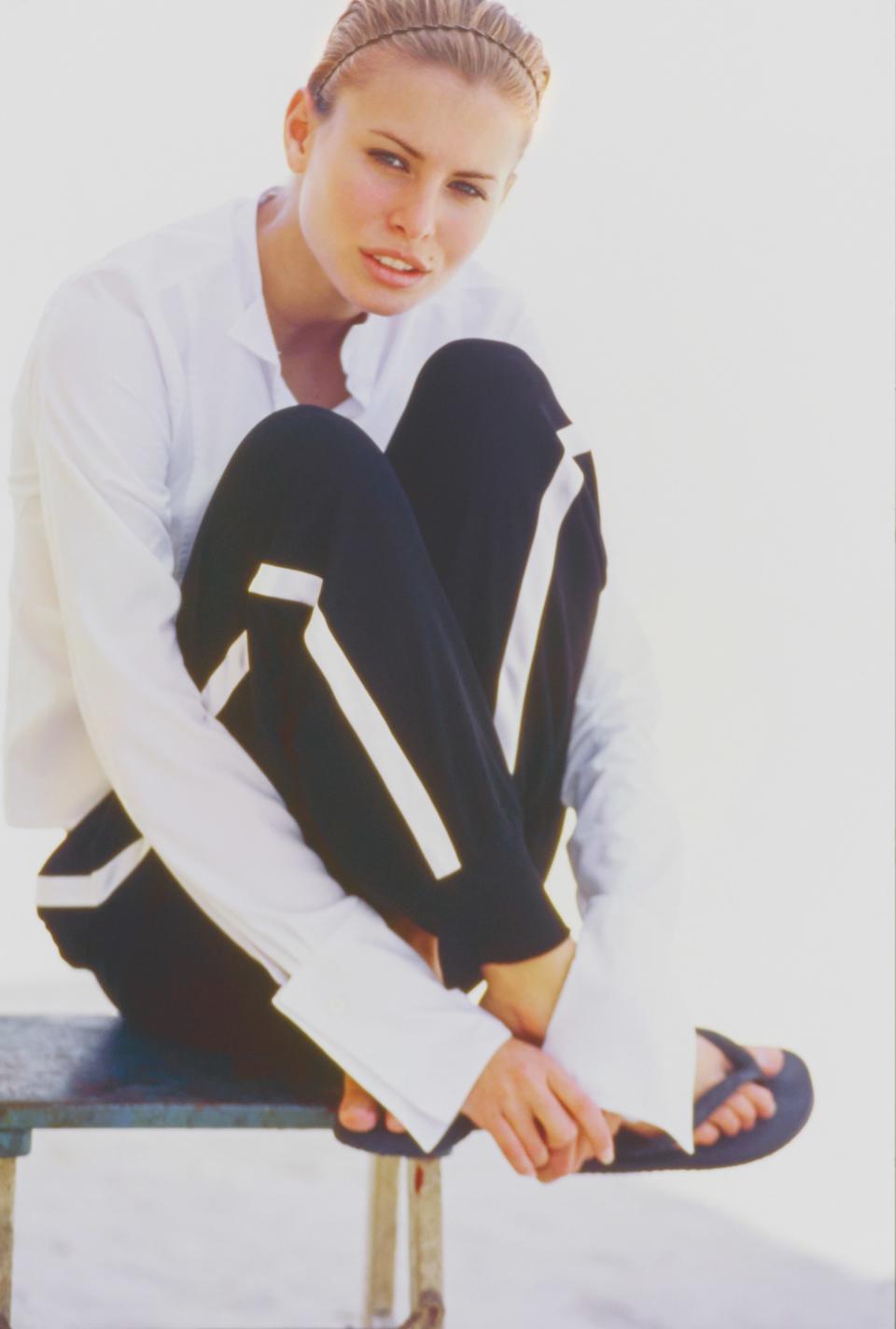

Shalom Harlow in Isaac Mizrahi Ensemble With Male Model in Yohji

There’s a lot of warmth in I.M., and a sense of domesticity, too; the yang to the yin of Mizrahi’s theatrical sensibility and irrepressible ebullience. Finally, Mizrahi seems to be living his best life, and it kind of resembles the one he imagined way back in 1990. “I think the new mood for the decade,” Mizrahi told Vogue at the time, “is to just miss the gala. If it’s a charity, send the check, get dressed up, and stay in.” As they say, fashions change, but style remains.