‘The Iron Claw’ and the Dallas Only the Dead Know

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

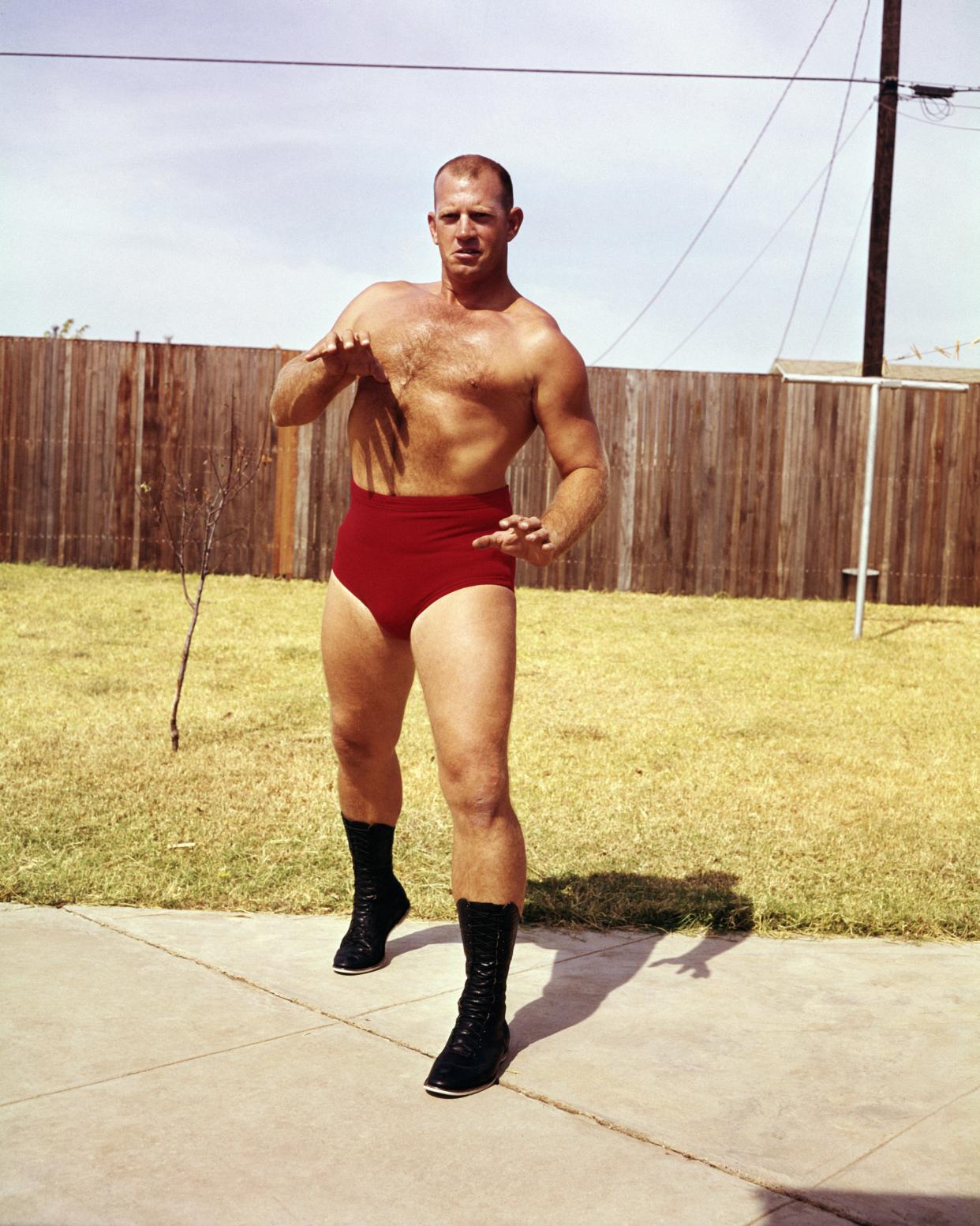

The Stanley Weston Archive/Getty Images

You cannot visit the Sportatorium. The Whisky a Go Go of 1980’s professional wrestling, Dallas’s crucible of scripted violence and shirtless melodrama, where fans full of this-is-real-to-me fervor once climbed down from the wooden bleachers to start fights with the wrestlers, is gone now.

Sportatorium truths and apocrypha still drift through wrestling culture. It was one of the first territories to use character-specific entrance music for wrestlers. A place where champions like Ric Flair and Harley Race defended their titles and where the men who would become Stone Cold Steve Austin and Mankind paid dues, where the same crusty hotdogs rolled for year after year on corroded old metal, where a mercilessly hard ring broiled in the Texas summer and went frigid with prairie wind in the winter.

Demolished in 2003, what was the Sportatorium is now a patch of grass beside a knot of I-35 and I-30 highway exchanges in South Dallas. All the suffering and entertainment and vitality has been rubbed out by Dallas’s smiling, relentless progress and left to go to literal seed. And, really, when we talk about the Sportatorium and wrestling in Dallas, we’re really discussing one set of ghosts: the Von Erich family, and one of the saddest stories in professional wrestling.

In the 1950s a guy named Jack Adkisson plays football at SMU and then decides to get into wrestling. A promoter sizes up Adkisson’s blonde hair and Teutonic vibes and gives him a gimmick: the Nazi wrestler. Not a sinister cartoon Bavarian nor an Otto-Von-Bismarck-esque soldier, but an literal (fictional) representative of the Third Reich. A persona is born. Jack Adkisson becomes Fritz Von Erich. Fritz does well but never becomes NWA world champion. He marries. He has six sons, the first born in 1952. He reaches the end of his in-ring career and takes over the Dallas territory. Builds a big family ranch in Denton County, an hour north of Dallas. Finds success as a promoter, elevating Dallas’s World Class Championship Wrestling to one of the leading US territories. His sons become wrestlers, because he demands that they do.

By 1993, five of the Von Erich brothers are dead. Jack, the oldest, dies in a childhood accident in 1959. In 1984 David dies alone in a Tokyo hotel room during a wrestling tour, either from acute enteritis (the official account) or from complications from a drug overdose, at least according to any number of memoirs and interviews with his peers. Mike, Kerry and Chris all die by suicide in the ‘80s and early ‘90s. The surviving brother, Kevin, inherits World Class, sells it, moves to Hawaii and raises a family far, far away from Dallas and from wrestling.

Director Sean Durkin's new film The Iron Claw tracks the Von Erich family’s fates across the 1980s and early 90s and centers on Kevin Von Erich (Zac Efron), the gentle eldest brother who lived to tell his family’s story. Durkin laces the story with visuals as haunting and striking as those in his debut film, 2011’s Martha Marcy May Marlene. The Iron Claw features some of the best professional wrestling scenes I’ve seen. The bouts are staged clearly, and illustrate the moments in which the faux sport becomes an art—desperation and triumph and pain and identity performed in real time. Efron’s body is a performance itself. He’s not just ripped in the contemporary sense, he’s yoked. He created the layers of muscle—the show muscles and the go muscles—that any good wrestler has to have to both look great and literally survive the beating.

Each Von Erich brother who wrestled embodied a Texas trope. David (Harris Dickinson) was the biggest, the most natural on the microphone, the “Yellow Rose of Texas” predestined to reach the apex of wrestling. Kerry (Jeremy Allen White)—a champion discus thrower thwarted by the US boycott of the 1980 Olympic games—radiated a last-scene-in-The-Wild-Bunch charisma, but had weak promo skills and a universally acknowledged drug problem. Kevin, the good son, wrestled barefoot, the platonic ideal of the Texas farm boy, and could do a little bit of everything in the ring. As Efron’s performance makes clear, Kevin lacked the idiosyncratic verve that one needs to become iconic in pro wrestling. The film gestures to the idea that the gentle, accepting temperament which held him back in wrestling likely saved his life.

The Iron Claw is also an ineffably North Texas movie. The film divides its narrative between the openness of the Von Erich family ranch in North Texas and the literal smoke-filled rooms of the Sportatorium in Dallas proper. The urban-rural, sin-salvation binary speaks to all things Texas. But what happens when pain and safety switch venues?

North Texas proper, around 15 counties and about eight million people, begins just south of the Red River that separates Oklahoma and Texas. Not long ago it was all farmland. Even today if you drive north from Dallas in a little over an hour you can gaze at the calves and Clydesdales on working family farms. You can still get an outstanding plate of fried green tomatoes from a diner where George Jones and Patsy Cline play on a loop. Beyond you, fields of clover and sorghum stretch over what was once called the Blackland Prairie.

The Von Erich family ranch plays that role in The Iron Claw. The ranch was located in Denton County, a place that was once farms and lakes built by the Army Corps of Engineers. The county seat, Denton, is quintessential Texas: a sleepy town square with the courthouse right in the middle. In theright bars you might be greeted with a How do. The local hippies and artists and readers and burnouts have safe harbor at the local state university. Even in the secular, pluralistic, post-internet 2020s, it’s easy to feel the pastiche of images there: dinner bell and Sunday best and working boots and Sir and Ma'am and the Baptist Church and the Methodist Church. Of course the Black and the Mexican and the Native histories in North Texas are all conveniently elided in these tropes, but if you drive through a town in nearby Tarrant Country named White Settlement, you may begin to understand why.

No other state infuses athletic competition—any sport, any venue, any stakes—with as much existential power as Texas does. Multiple high school football stadiums in Dallas-Fort Worth dwarf Division 1 football stadiums. The most niche Montessori, Waldorf, We-Are-The-World private school will celebrate their state soccer title in the smallest private school division like Argentina celebrating the World Cup.

I’ve lived in Dallas for six years so I speak from experience when I say that Dallas-Fort Worth is the Champagne region of deranged sports dads. Think high school sports coverage pitched at the intensity of war reporting. Think youth football arguments that turn fatal. I’ve seen unhinged fathers fume silently at their 5-year-olds’ timid performance and yell at 16-year-old referees. I’ve coached soccer “against” the dad on the other sideline who barked “No let up!” from behind his reflective aviators as his team of 5-year-olds ran up the score on our team of 5-year-olds. After the game he gathered his buddies to cavort at the center circle in their never-seen-a-stirrup cowboy boots and triumphantly vape.

At the event horizon of brutal Texas dads stands Fritz Von Erich. In The Iron Claw, Holt McCallany plays Fritz like a mix of The Great Santini and Mommie Dearest. After David Von Erich dies, Fritz gathers the brothers on the porch of the ranch before the funeral and launches into a speech about how David was scheduled to win the world championship and now one of them—one of the grieving, devastated brothers—must take David’s spot and win the world championship in his stead. This isn’t a family; it’s a platoon. As David Shoemaker wrote in his book Squared Circle: Life, Death and Professional Wrestling, Fritz “would try over the rest of his life to script reality to suit his fantasy.”

Wrestling becomes the family’s pitiless onscreen love language. Instead of hugs and listening, the boys learn the titular Iron Claw, their father’s finishing move that requires someone with huge hands—a Von Erich family trait— to envelop their opponent’s face with their right hand and squeeze. In the film, the brothers teach each other how to apply it. At the Dallas premiere of the film, Efron and White and Kevin Von Erich himself hit the Iron Claw pose for the cameras, left arm grabbing the right arm at the wrist, right hand open with each finger at full stretch like a squid ready to rend its prey into pieces.

"The Iron Claw" Dallas World Premiere

The movie swings between the Von Erich ranch and the Sportatorium. At the start of the film, the latter location houses all the pain, and performance, and familial angst. And then it shifts. The positive pastoral vibes in the first glimpses of the Von Erich ranch—post oaks and miles of grasses and resilient, gnarled brush—drain away, and the ranch becomes a purgatory where the survivors mourn, eat, and try to keep wrestling.

I find it revealing that so many who thrive in a city that thrives on turning the rural into the urban—pumping the ground, mixing cement into concrete, adjusting mezzanine capital, landing the strip-mall expansion—dream of open land where they and their family will be more at ease, closer to a country living scrubbed free of the actual labor of rural life. In my first year of living here, when I was working as a tutor, I drove to a student’s ranch in Parker County west of Fort Worth. I got to the end of the road. The literal end. I could see brass-colored fields in the full afternoon light, thin wire fences, the raw red head of a juvenile vulture checking me out from a telephone pole. This was the frontier that people were so eager to churn into sub-developments.

Dallas itself is the omnipresent boom town of the moment. Pick your study or article. It’s going to be bigger than Chicago any day. Fortune 500 companies continue to move entire operations here at a brisk pace. International-caliber museums dot both Dallas and Fort Worth. There is luxury retail and nightlife and convention centers and private schools commensurate with a major city. The desire to become an alpha is palpable. Contemporary Dallas’s communal thirst to be taken seriously, to be spoken of with Chicago and Los Angeles, is perhaps its most naked flaw.

Houston has the blue-collar charm, a flinty life closer to the oil rigs and the bayou and the Gulf, air enmeshed with refinery haze; Harris County’s Creole and Vietnamese and Nigerian kitchens; the sodden, sprawling ring roads enshrined by DJ Screw and UGK. Austin is Texas 2.0, simulacra of fancy barbeque and rich-kid student films and giddy tech vampires and Keep Austin Weird shirts 25 years past their sell-by date.

Even Fort Worth, Dallas’s neighbor, provides the purer Texas fantasy: the stockyards and the Chisholm Trail and old F-150’s lovingly caked with dirt, authentically polite teetotaling Methodists with 70 million dollars of mineral wealth sitting quietly in a local bank, the city where the son of a cardiologist can plausibly offer himself to contemporary Hollywood as the Last Texan and Red State oracle.

But Dallas? Haunted, uncool, materialistic, understudied, deeply second-tier and determinedly urbane at the same time. Try-hards in Bottega Veneta, their endless oil-and-gas money gleaned from other people’s sweat. Dallas is the America that America don’t want to show.

And yet the city has a seductive appeal. When Nobel Prize winning writer and expert chronicle of empire V.S. Naipaul covered the Republican National Convention in Dallas in 1984, he wrote: “Air-conditioned Dallas seemed to me a stupendous achievement, the product of a large vision, American in the best and most humane way: money and applied science creating an elegant city where life had previously been brutish.”

Naipaul was right. Like Jack Adkisson smoothing the edges of professional wrestling for his little family empire, Dallas loves to smooth the boundaries between country and city. Here you get a luxury car to cosplay city rich, then you get actually rich, then you buy a recreational ranch to cosplay country.

Maybe only Miami enjoys money on as pure a level as Dallas does. I’ve seen men in stingray cowboy boots chatting through their manicures and heard a waiter in an expensive restaurant share a bawdy anecdote from their childhood in the Panhandle as they uncork the Krüg. One of my first weekends living here, I went to Deep Ellum, a neighborhood as essential to early blues recordings as New Orleans was to jazz. It was the peak of a Friday night. I saw a glistening new canary-yellow Porsche with paper tags and a license plate frame that read PORSCHE OF SHREVEPORT crawl down Elm Street. A young woman drove and her friend rode shotgun, the top down, their hair in the wind, sugar money and refinery money drifting in their wake.

What Northern Ireland is to poets, DFW is to child stars (Selena Gomez; Demi Lovato; Kaitlyn Dever; etc.). Local Millennials and Zoomers will argue that Dallas is the progenitor of “bro” as an omni-race omni-gender pronoun. There’s exceptionally good eating here: Lao, Viet, Ethiopian, various sub-genres of barbeque, seafood from Sinaloa, pozole from San Luis Potosi, Iraqi bakeries, a half dozen steakhouses so thoughtful and so good that they make one reconsider the entire genre. AT&T Stadium absolutely rules. I’m the son of a Philadelphia Irish sports zealot and—forgive me father—when I was a guest at a Cowboys game, I bought Cowboys gear for my then-infant son and snapped up a Michael Irvin shirt for myself. I hit the Emmett Smith shimmy in a hallway. I regret nothing. Critics would say that Dallas was built to house the money. Yes, it was. As were Milan and Hyderabad.

But the best recent art about Dallas and North Texas can’t shake the revenants of the past. Maybe that’s Dallas’s contribution to American culture: the reminder that money and ambitions cannot pierce the ghosts. Two of the better American novels of the past 15 years are set in Dallas. Merritt Tierce’s novel Love Me Back follows a woman working in one of Dallas’s luxury steakhouses and unravelling at night. Ben Fountain’s Billy Lynn’s Long Halftime Walk dances along the hypocrisies of sports and war and the invincible rich men who confuse the latter with the former and leave it all on the heads of the young men who do the dying. On the cover of the best album (2015’s Down By The Trinity) from the best Dallas rap group (The Outfit, TX), figures wrapped in black cloaks face a white cross as a Confederate Flag burns in the background.

In The Iron Claw’s most haunting scene, Zac Efron’s Kevin temporarily abandons his young family, and sleeps in the office of the Sportatorium. He worries aloud to his young wife (Lily James) about giving his children his family’s curse. His childhood home in the country has become a center of Old Testament suffering. He can’t go there. He won’t be with his own family. So he puts himself under his father’s desk in Dallas and curls into the fetal position in the dark. Absence even lingers on the corners of The Iron Claw itself. Chris, the youngest of the Von Erich brothers, isn’t a character in the film. Made small and frail by a heavy prednisone regime to treat bad asthma, Chris wanted desperately to wrestle with his brothers. He could not. He was the last suicide.

If you’re lost enough in Dallas you can find what used to be the Sportatorium. You can find the patch of grass with parched, cowed trees at the edges. No plaque nor sign marks the lot. But if you park at the gas station across the way, and walk across the service road, you can step onto the land. You can see the Dallas skyline, the wave of redundant proud towers, the place that “turn[ed] a billion steers/Into buildings made of mirrors,” as David Berman sang. You can imagine what it might once have been like: the crowd, the willpower, the desperate effort that the Von Erich boys put themselves through to please an immovable father. You can imagine the sounds and the joy and the darkness, the nothing that isn’t there, and the nothing that is.

Originally Appeared on GQ