This Iraq War Vet Cheated Death 3 Times. He's Proud to Cry About It.

FROM ABOVE, YOU WOULD have seen two battered Humvees streaking down a rutted freeway, one behind the other in the center lane, surrounded by miles of Iraq’s parched terrain. As they approached an overpass, one moved into the far-left lane and the other moved far right. Afterward, the trucks weaved back into the same lane.

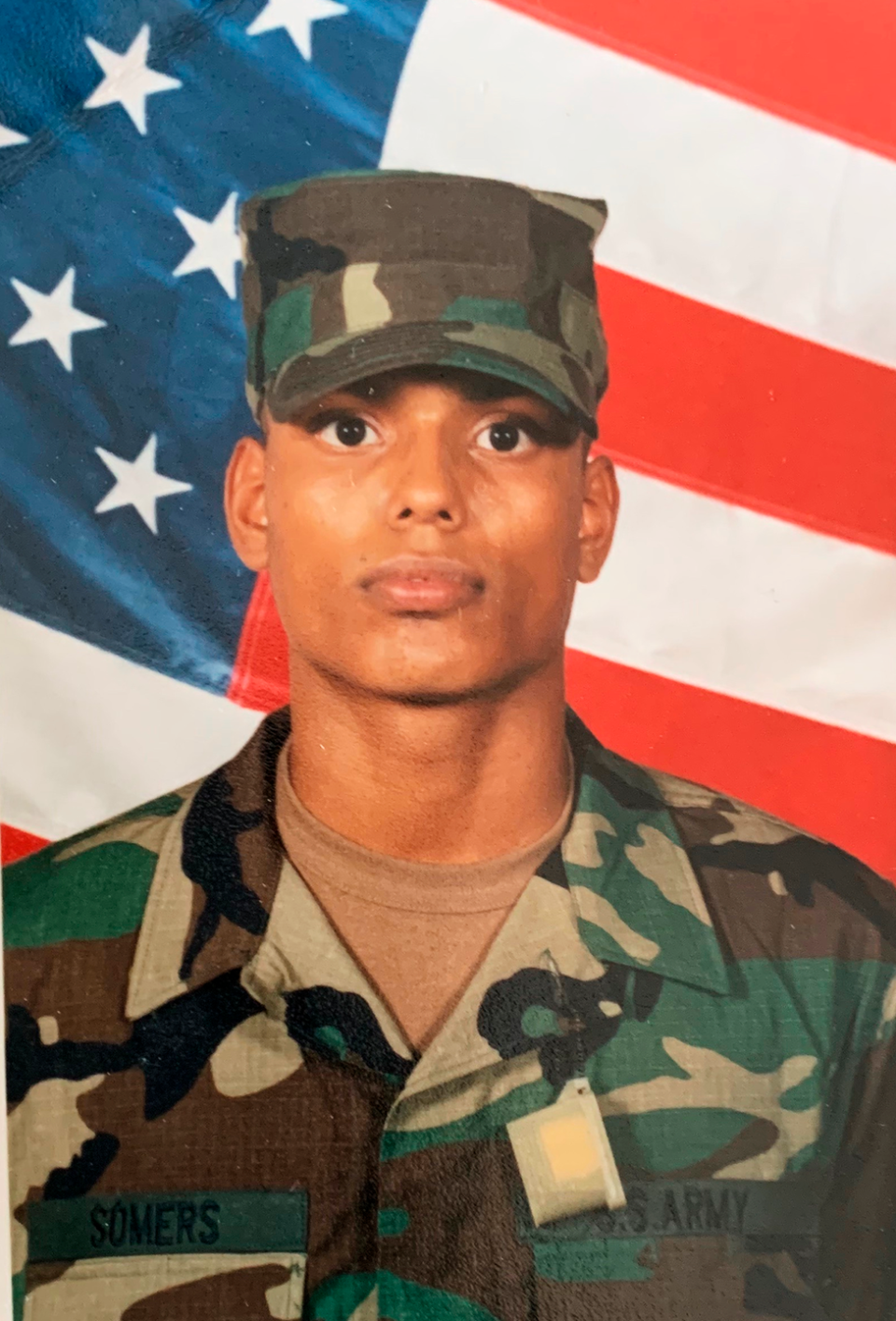

It was July 2003, and trucks were getting blown up every day in Iraq—insurgents often dropped grenades from overpasses. Bobby Somers, a 23-year-old specialist in the U. S. Army, sat behind the wheel of the second beat-up Humvee, fondly code-named Bertha. Clad in tan fatigues, he had one hand on the wheel, the other on a machine gun pointed out the window. A tiny earbud snaked into his left ear, pumping 50 Cent’s Get Rich or Die Tryin’ album from a CD player tucked beneath his seat. Somers had driven thousands of miles like this without incident, and he felt invincible.

As the trucks emerged from another overpass, Somers saw the orange Mirinda soda can clink, clink, clink across his truck’s hood. In a split second, he registered that the can was cut open, with a pineapple-shaped grenade inside. He saw light shoot from the cracks as it blew up.

The blast shattered Bertha’s windshield, shooting glass into Somers’s face and ears. Because the truck was moving at such high speed, the wind blew a lot of shrapnel away from him. He survived and returned to duty soon after.

That was the first time Somers almost died. The second time was the following January. Now with a little more armor—he’d started wearing his neck protector—Somers was driving again when someone fired a howitzer. He doesn’t remember much after that. “It felt like God had a bat the size of my body,” he says. The shell pushed the Humvee over more than a full lane as it exploded.

Somers woke up a few minutes later in a panic. He thought he was late for high school football practice. Then he saw the gunpowder, the dirt, and the blood. He was taken to a field hospital. His first sergeant sat next to his bed, shaking.

After both attacks, Somers was offered a medical discharge, but he stayed. “I remember when I got back into that truck, I was crying,” he says. “I didn’t want to drive out the gate. But I was more scared to let people know I was scared.”

Which brings us to another time Somers nearly died, years after he’d finished his tour, while at his home in Texas. He went into his bathroom, put a gun in his mouth, and almost pulled the trigger. Fate had intervened twice to save Somers’s life. Now he would need a different kind of help.

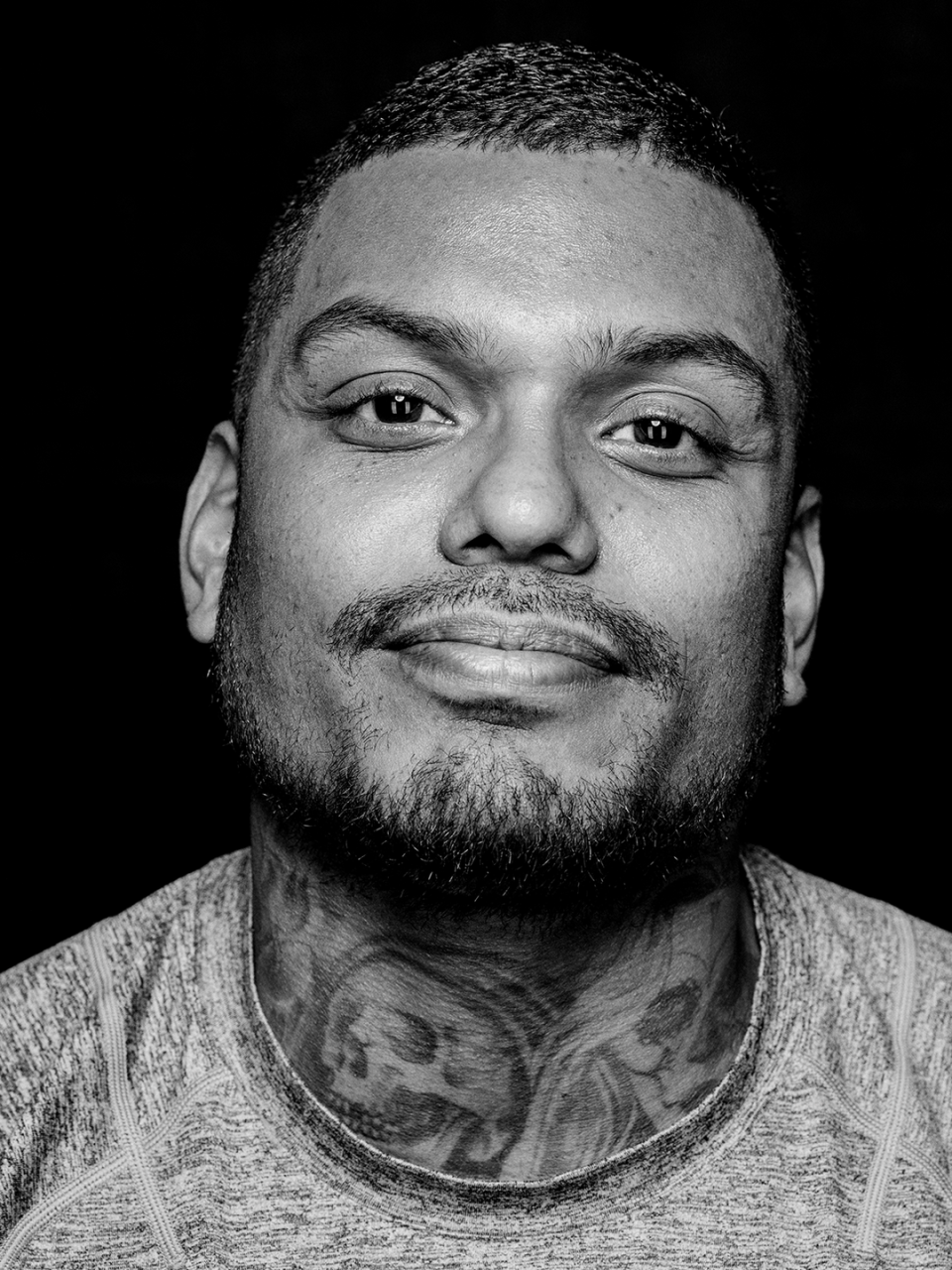

"I WAS A SOLDIER," Somers, 39, says on the day I meet him, as if that somehow explains everything at once. We’re at Performix House in Manhattan, the mother ship of Performix, a brand that began as a line of supplements and has grown to include a vast elite gym.

Walking into Performix House is like throwing open a warehouse door to a secret, futuristic special-ops training facility. Fit men and women, almost all wearing gray and black, are chatting and idly stretching everywhere. Somers looks like everyone else at Performix House—intimidatingly built and endorphin-cheerful—except that he has way more tattoos. He started getting them to cover scars, he says, pointing to a shiny spot on one arm where the ink didn’t take.

Somers came to Performix through a foundation run by founder Matt Hesse called FitOps. The group operates a three-week program that teaches veterans to apply their skills to personal training. Somers now volunteers as FitOps’ head chef.

I was a soldier. That partly explains why Somers felt duty bound to stay and protect his comrades despite his injuries, why he never complained when he started to feel afraid of going outside the gates, and perhaps how he compartmentalized his trauma almost to the point of self-destruction. It doesn’t explain how he survived his inner monsters: PTSD and traumatic brain injury from both attacks.

That’s where Matt Hesse comes in. Hesse, 42, transitioned out of active duty when his mother was paralyzed in a car accident, but he wanted to help his fellow veterans. He founded FitOps in 2016 and has since enrolled more than 300 vets. In week 1, personal trainers talk about the industry. Week 2 covers marketing and business practices. Week 3 involves practicing client assessments, doing mock job interviews, and prepping for the C.P.T. (certified personal trainer) exam.

The true game changer, however, is what Hesse and Somers call the “circle of tears.” Every night, Hesse gathers the class, roughly 40 men and women, and invites them to describe not only why they are there, but what led them to this point in their journey. As in an AA meeting, it’s freeing for veterans to tell their stories to people with shared experiences—there’s no judgment and total understanding.

When Somers arrived for his training in 2017, he’d spent 12 years trying to distract himself from his mental pain: with classes, and with drugs and alcohol. In the circle of tears at FitOps, he faced it head-on.

There were issues before the attacks. Somers grew up in El Paso, Texas, among drug cartels and gang members. He was the child of an affair, and his skin was darker than his siblings’. People called him cerillo—match in Spanish; they meant he looked like a burnt matchstick.

Somers recalls being beaten. He remembers using bleach in the shower in an attempt to lighten his skin. “I thought all brown kids got treated that way,” he says.

He did look up to an uncle, a veteran who had joined a cartel. He saw his uncle’s beautiful house, his car, his wife, and his wallet, fat with cash—always cash. That’s what I’m going to do, Somers thought. I’ll be a gangster, and then a soldier. When I’m done, I can go be a gangster again.

When he got to Iraq, all Somers cared about was being badass. That was what grit meant to him. His unit called their base San Quentin, because there wasn’t much to do except lift weights before missions. He could bench 315 pounds, but his first sergeant—the one who later cried next to him in the hospital—could bench 400. Somers wanted to catch up. “That was literally one of the biggest things I was worried about,” he says now with disbelief.

In July 2004, seven months after being blown up a second time, Somers returned to the U.S. “I was still so worried about dying every day,” he says of his overseas deployment. “It didn’t hit me until I had nothing to do.”

He began seeing doctors about his injuries but wouldn’t be diagnosed with PTSD and a traumatic brain injury until 2011. In 2005 he attended recruiting school, and for the next three years he worked 18-hour days as a military recruiter in Upland, California, trying to keep his mind occupied. There he met his now wife, Nicole, who was also in the service. In 2010 he moved to Fort Bliss, Texas, where he was given a medical retirement. Next came welding school, and after he graduated, he enrolled in culinary school.

Somers started working as a private chef, cooking healthy meals for clients at gyms and for some reserve soldiers. One day, one of them—arriving with a chaotic carful of dogs, as godsends often do—told him about FitOps. She said it was offering free certifications for physical trainers. (Not quite: FitOps is free, but certifications are hard-earned.)

By August 2017, he was married and had kids. Somers thinks often about the suicide of Linkin Park singer Chester Bennington, and the video that Bennington’s wife posted of the day before his death, in which he’s laughing and playing with his family. He thinks about Robin Williams. “That dude was supposedly the happiest guy in the world,” he says. “But like with me, sometimes the voices just get so loud.”

When they got too loud for Somers, he put a gun in his mouth. He only stopped himself because he realized he hadn’t said goodbye to his daughter that morning. He could wait a minute. He learned he’d been accepted to FitOps that day. It could wait just a minute more.

WHEN HESSE FIRST MET Somers, the tattooed vet was crying under a table in the FitOps barracks. On its surface, FitOps gives veterans new practical skills, but Hesse also credits it with helping them open up to one another about tough experiences. Somers had struggled to share his story, and the prospect of facing trauma overwhelmed him.

“He had an extreme loss of purpose, combined with several brain injuries from war,” says Hesse, who has become close with Somers. “And his story goes back further even than war. He was dealing with what I call ‘multiple compartmentalizations.’. . . The thing that the military teaches you very well, through excruciating fitness and physical pain, is how to compartmentalize.”

Somers had been a master compartmentalizer since childhood. In the Army, that was a strength—it allowed him to climb back behind the wheel after getting blown up. But when he returned from Iraq, it became a weakness. Bottling up any trauma can be destructive. “When you get home, if you don’t unlock those compartments and deal with them one by one, eventually they will overtake you,” Hesse says. “That’s where suicide happens.”

FitOps, which counts zero suicides among its alumni, cracked Somers open like that first grenade did. For most of his life, he had been motivated by men around him—his cartel-wealthy veteran uncle, or his hardcore first sergeant. In telling his story, and seeing how other people were affected and moved to tell theirs, Somers found his own strong sense of purpose.

“To keep acting like I don’t have these conversations in my head is stupid to me,” he says. He still has suicidal thoughts sometimes, but he talks about them readily, always in unvarnished language. “People like to be like, ‘Well, you know, a soldier might want to hurt himself.’ Say ‘suicide.’ ” That’s what kills an average of 17 soldiers a day, according to 2017 data from the U. S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

In Hesse’s terminology, this is called “creating a bigger blast radius”: The more one veteran can learn to open up, the more others in his or her community might feel okay doing the same. Somers cries often now. He doesn’t wipe the tears away or try to hide them. While we talk at Performix House, they flow freely down his cheeks.

After graduating from FitOps, he stopped searching for the next thing. He has since become an ad hoc FitOps spokesman, recently telling his story in an online testimonial alongside John Cena, a vocal and financial supporter of the mission.

“My job, till I die, is to let men know that we have tear ducts, just like an exhaust pipe,” Somers says. “I’ve had the gun in my mouth,” he says in the video, tearing up. Lately, more veterans have been approaching Somers in tears. “Big dudes, like big muscle dudes. And they’re like, ‘Thank you.’ Hugging me. Crying. Maybe—not even maybe—that’s what I’m here for.”

You Might Also Like