New 'inverse vaccine' could wipe out autoimmune diseases, but more research is needed

Scientists have created a new type of vaccine that instead of activating the immune system, selectively suppresses it. The so-called inverse vaccine, which has only been tested in mice so far, could one day be used to treat autoimmune diseases, in which the immune system attacks the body, the researchers say.

The vaccine was given to mice with a condition similar to multiple sclerosis, an autoimmune disease in which myelin sheaths, or the insulating coats around nerves in the brain and spinal cord, are systematically destroyed. The treatment reversed symptoms of the disease and restored the function of nerve cells. The findings were described in a study published Sept. 7 in the journal Nature Biomedical Engineering.

The vaccine essentially works by getting the immune system to recognize nerves as "safe," rather than as foreign invaders that should be attacked. The method hasn't been tested in humans, but experts told Live Science that the results are exciting.

Related: In a 1st, scientists use designer immune cells to send an autoimmune disease into remission

"The idea of inducing tolerance in autoimmunity has been around for a while," Nick Jones, an associate professor of biomedical sciences at Swansea University in Wales who was not involved in the research, told Live Science in an email. But although the concept isn't new, this study is exciting because it showed this approach worked to alleviate, at least temporarily, autoimmune disease, he added.

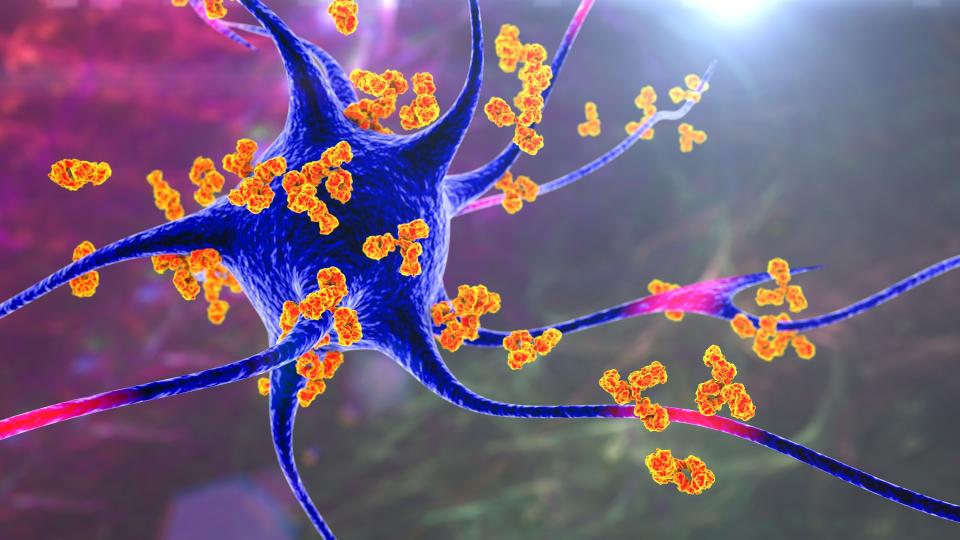

Normally, immune cells called T cells protect the body from invaders like viruses and diseased cells, such as those in cancerous tumors. They identify which cells to attack by binding to specific antigens, or molecules, that typically appear on the outside of a virus or cell. However, in autoimmune disease, T cells mistakenly target healthy cells in the body by going after "autoantigens," molecules found only on those normal cells.

How do you get the body to stop attacking itself? You teach it to leave those autoantigens alone — and the body has a way of teaching this tolerance.

This teaching is done by a special group of cells in the liver that present antigens to T cells and tell them that they're safe; the liver has these special cells because, while filtering blood, it must differentiate between dangerous foreign antigens (from bacteria) and safe ones (from cells from one's self and food). In the new study, the researchers hijacked this process to mark the body's cells as "safe" from T-cell attack.

They induced a form of multiple sclerosis in mice, which caused T cells to attack a specific antigen found in myelin. To stop the attack, they then tagged this antigen with a special sugar, and those sugar-tagged antigens got ferried to the liver, where the tolerance-teaching cells picked them up. The liver cells then reprogrammed T cells to leave myelin alone as well as protect it, essentially removing myelin from the immune system's "hit list."

Related: The virus behind 'mono' might trigger multiple sclerosis in some

Inverse vaccines like these are exciting for a number of reasons, experts told Live Science.

Firstly, the vaccines would suppress one cell type in the immune system, unlike many standard therapies that exert their effects more broadly. "Most immune therapies for autoimmune diseases act in a general way and don't just target the disease-inducing T cells," Lucy Walker, a professor of immune regulation at University College London who was not involved in the research, told Live Science in an email. "Ideally, we'd want suppression to act in an antigen-specific way, so only the pathogenic T cells are targeted and others are left free to function." This means you could avoid side effects, such as the increased risk of infection associated with using standard immune-suppressing therapies, such as methotrexate.

Vaccines also stimulate the formation of immunological memory, or the body's ability to remember infections so that it can better respond the next time it encounters the same invading microbes. "Current therapies for autoimmunity are really sort of broad immune suppressants and they work while you're taking them but when you stop taking them, they stop working," study senior author Jeffrey Hubbell, a professor of tissue engineering at the University of Chicago, told Live Science. "The idea with the vaccine is that you develop memory of that therapy."

However, although the results of the new study are promising, more work needs to be done to develop this technology into a treatment that can be feasibly used in humans, Walker said. For instance, the protective effects shown in the study only lasted a few weeks, so it is unclear how long they could last, especially in people.

Another potential issue is that the immune system could regain its memory of the target antigen, which may mean a booster dose would be needed, as is the case for many regular vaccines. Hubbell said that this is something that clinical studies will have to investigate.

Success in animal models also doesn't always translate to humans.

RELATED STORIES

—Teen's year-long case of depression and seizures caused by brain-injuring autoimmune disease

—COVID-19 linked to 40% increase in autoimmune disease risk in huge study

—Woman who spontaneously vomited up to 30 times a day likely had rogue antibodies

"It's unlikely that a single approach will work in all humans with a particular disease because these diseases have more variation in the human population — in part, because people are genetically very different from each other, including for genes that are important in the immune system, so they respond differently," Dr. David Fox, a professor of internal medicine at the University of Michigan who was not involved in the research, told Live Science.

Another tricky issue is that for each autoimmune disease, scientists will have to identify the specific autoantigen that the body is primed to attack, which Jones said could involve an "extensive amount of research." For some autoimmune conditions, such as psoriasis, there isn't a consensus on what the autoantigen is, Fox said, and in multiple sclerosis, for example, there are several autoantigens that are known to be targeted by the body's immune system. This may make it difficult to measure the benefit of treatment in humans, he said.

Nonetheless, this approach of using sugar-modified antigens to dampen an autoimmune response has already been shown to be both safe and effective in early clinical trials for celiac disease — an autoimmune condition that injures the small intestines when those affected eat gluten. A second trial is also currently assessing the safety of the approach for patients with multiple sclerosis.

"It's a really exciting area of research," Walker said, although it's lagging behind other types of immunotherapy, such as Teplizumab, which was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to delay the onset of type 1 diabetes. Regardless, "I do think it's a promising area for the future," Walker said.