International Library of Fashion Research Officially Opens in Oslo and Is Free to All to Explore

Four years after Elise By Olsen and her late mentor Steven Mark Klein “wrote this very brief elevator pitch” to propose the International Library of Fashion Research, the doors of the Oslo institution have opened.

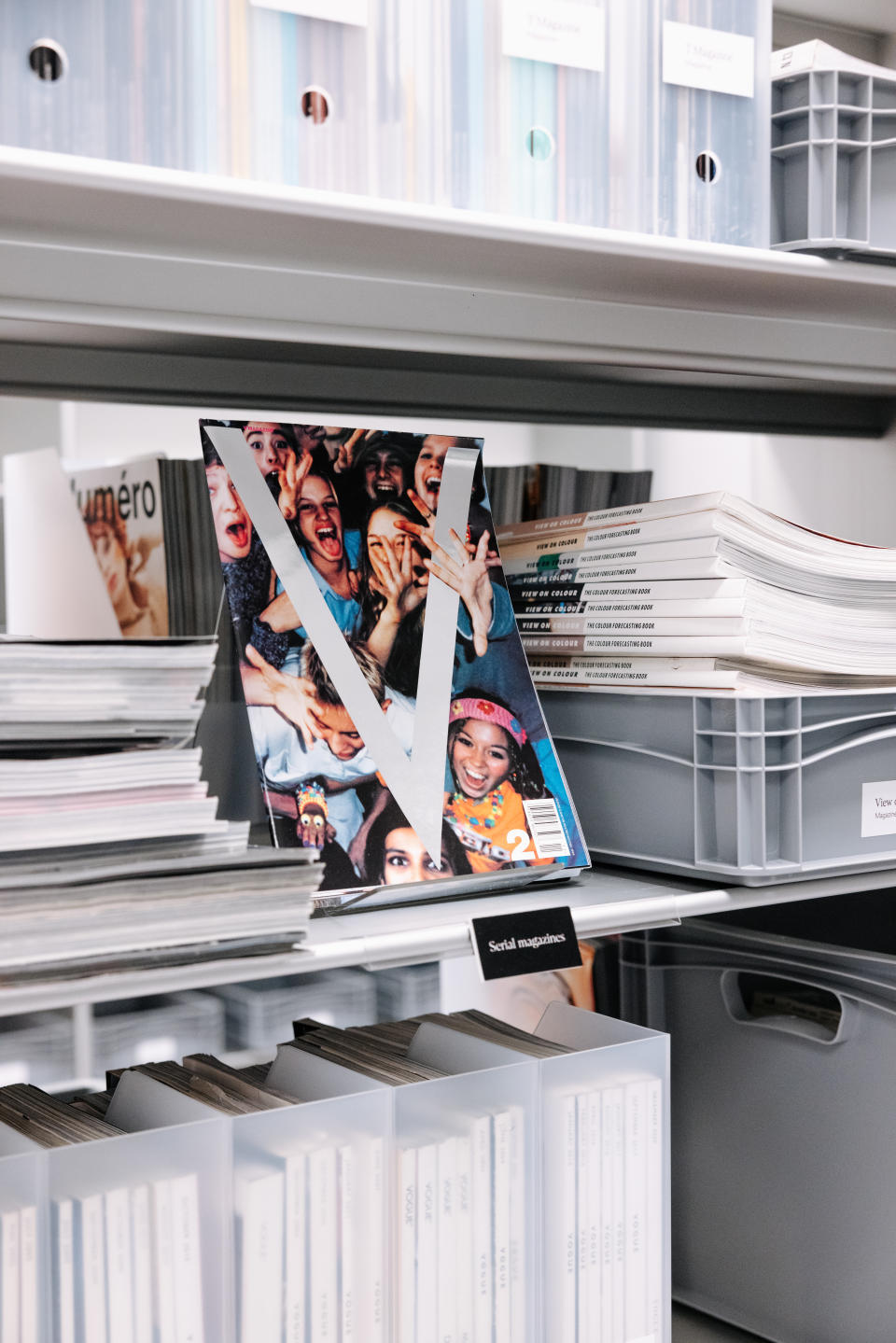

Having debuted digitally in the fall of 2020, the institution’s physical outpost is now officially up-and-running at one of Oslo’s prime addresses. Housed near the National Museum and on the same campus, the library spared the historic site from demolition and is also close to another major landmark, the Nobel Peace Center. Designed to be “the world’s most comprehensive repository of specialized fashion research and contemporary fashion publications,” the ILFR is geared for researchers, industry professionals and everyday enthusiasts.

More from WWD

During an interview last week, OIsen recalled making the pitch to Norway’s National Museum, which had already approached her about curating an exhibition. Game as she was for that endeavor, the idea of starting a library was also floated with, “’To whom it may concern at the National Museum, I want to found a library for fashion research.’ It was extremely naïve. I just revisited that letter the other day and it was very precious.”

The let’s-give-this-a-whirl approach has served her well. “This is how it’s been with everything that I have set out to do. I didn’t know anything about print magazines when I started my first magazine [Recens at the age of 13]. I’m a firm believer in just learning, as we go and trial and error. Of course, quality is important, but learning by doing has been very important for me,” Olsen said. “…I just turned 23. I was speaking to my mom about how I’m having my tenth anniversary in the business, in the industry.”

Housed in a former train station, the intimate space is a switch from many of the museums, galleries and “of course fashion retailers” that take “a more-is-more” approach, the founder said. “Its view of scale is also similar to Wallet magazine [which Olsen started years ago for a decade-long run].” That publication was formatted to be a little bigger than the size of an iPhone despite coffee table-sized magazines and books were then the dominating format. Anticipating that the library will quickly outgrow the space, she mused that maybe the Norwegian state should build us a big library.” State funding, private funding and a good chunk of Olsen’s savings account are funding the project.

The ILFR’s study space occupies about 1,600 square feet on the upper level and a 8,100-square-foot exhibition space is below. The opening exhibition, “For Immediate Release: The Art of the Press Release,” features materials from Maison Martin Margela, Alessandro Michele, Walter Van Beirendonck, Prada, Mowalola, Sunnei, Virgil Abloh, Angelo Figus, Comme des Garçons and others. A 26-minute satirical film on loan from the Cooper Hewitt National Design Museum features WilliWear designer Willy Smith, an apparent jest of press releases as a way of communicating fashion.

Adept at seeing through things, Olsen said, “What we have seen over time is that fashion press releases have become very contemporary art press release-oriented with very abstract and grandiose language. It’s not experimental. It’s rigorous ways of talking about fashion. It’s moved into that direction of overexplaining, over-conceptualizing.”

Cue to the library’s motive of preserving fashion’s past while grasping the present and furthering its future, Olsen noted that as press releases have gone more digital, there aren’t as many physical ones being distributed. “It’s also a very disposable format. People write their collection reviews and then they get rid of the material,” she said.

Trolleys lined with materials that others requested to review will be placed in the aisles so that visitors might have another sense of discovery. “It’s kind of this physical algorithm, interesting to track down what kinds of material people who have been there before you grappled with,” Olsen said.

Planning to have exhibitions roughly every third month, the library wants visitors and readers to understand how an institution works and the economic apparatus that is required to make it run. “Maybe the exhibitions won’t overlap [from one to the next] or maybe one month we are running out of funds or lacking a sponsor. Then the exhibition can just be empty or we can have local people coming in to fill the space.”

Mutual friends of hers and Klein’s will be at Tuesday’s opening, as will fashion thinkers, experts, museum directors, industry professionals, IFRL collaborators and wish-list people whom the organization would like to work with in the year ahead. “Our main mission is to create a space for international fashion thinking and critical fashion thinking,” she said. Far from finished, she sees the free public library as always developing and growing.

Interestingly, designers will not be the absolute zenith of the library. Recalling how the proposition to Oslo officials stemmed from last fall’s IFRL-organized symposium, Olsen said that explored, “‘What happens when you create a fashion ecosystem where the designer is not necessarily in the center?’ Of course, we have a lot of designers in the center. The biggest part of our collection is printed promotional material from designers. But what happens when you invite architects or fiction writers, contemporary artists or any non-fashion people into a space like ours? There is a lot of magic that can happen by mixing fashion discourse with other cultural fields — without disregarding fashion, of course.”

The grand opening will be incomplete for Olsen due to the absence and continued influence of Klein, who took his life last year and is always on her mind. After he emailed her cold in 2015, a friendship bloomed and daily calls followed.

“It’s such a shame that he’s not with us and it’s going to really affect the opening too. This was a project we started together. It was this cross-generational idea. Looking back after his passing, I understood that he felt that his work and research was completed, and he was passing on the baton. At least I am able to think about it in a pro-active way, which I am forced to do after something so tragic happening. It’s beautiful to have his legacy here, to develop it and really honor him,” Olsen said. “I didn’t inherit the collection after his passing. That’s important. He was very much in good health and good spirits when he gave it to me. We were working on it together.”

That said, the loss of Klein was so profound that Olsen could not go into the library for three months and she relied on her assistant to do so. “I did not want to go in. It’s such a personal collection and his energy is really present in that collection. It’s taken time but I’m coming to terms with it a lot more. And I am trying to use that energy in the best way possible,” she said, emphasizing that although she found herself forced to make it happen, she did so not on her own..

In hindsight, she hadn’t realized what a big deal it would be to make it happen especially in Oslo, where philanthropy is limited and there are very few private institutions. “There is this idea that culture is sort of state-funded. To an extent, I agree but also it was very hard to come into that landscape. Seeing things through took some perseverance.”

The space was lined up during the pandemic in May 2020, and that delayed the initial opening plans. A knee injury sidelined the founder on sick leave for 14 months. On top of that, when the Norwegian-born Olsen first returned home, she had done so because her father was unwell. Having previously been living out of a suitcase traveling for different projects, she was unfamiliar with Norway’s fashion scene and cultural landscape at that time.

Somehow it all came together, partially due to the National Museum providing the site. Seeing shipping containers filled with 4,410 pounds of Klein’s collection slam harborside on Oslo’s docks also made the endeavor more concrete. Last fall’s symposium proved to her there is an audience for the ILFR, due to the number of students who paid to fly to Oslo for the event, as well as by the number of local students and industry professionals who attended.

It recently dawned on her that the all-out pace isn’t about to calm down with the opening after so much hard work. “This is not the case. This is when all the fun work starts with programming, curating and editorial projects in relation to the library. This is just the beginning,” Olsen said.

Best of WWD