How an Instagram Poll led to a Free Soloist’s Desperate Flatiron Rescue

This article originally appeared on Climbing

There aren't too many things that embarrass me these days. But here's a hard admission: I got scared as hell trying to solo the second Flatiron. I made it about halfway before I cowered into a ball and then resigned myself to start butt-scotting down. It's amazing that I didn't tear my tights. Or start crying. This is the same year that I sent The Crew (5.14c). I've been climbing for nearly 15 years, and I think I'm afraid of heights.

Let me back up.

***

The story really starts with my friend, whose mistakes I should have learned from.

Zach is a talented D.J. living in downtown Denver. He has bright blue eyes and a mane of curly mocha-colored hair. He's well-spoken and easy going and, consequently, he has many friends, which was perhaps to his detriment. Again, I'm getting ahead of myself.

Zach had been climbing for a few years. Mostly in the gym, but a few times outside. He was solid on plastic 5.11s when he attempted to solo the Second Flatiron in Boulder, Colorado.

"I failed the first time," he told me. "I kind of got it into my head like, 'Oh, it’s gonna be easy. Like I can climb this. I lift heavy things'"--Zach was "super into fitness" at the time--"'I could easily climb a rock, no problem." Despite his confidence, he got about halfway up before conceding to his fears and descending the gutter (a class four gulley that runs on the right side of the popular soloing route).

By the summer of 2021, Zach had more climbing experience. A lot more. He soloed the second flatiron four or five times, his nerves long gone. He recognized, in retrospect, that he'd grown overconfident. Summer passed. Fall passed, too. Zach had hunkered down in the gym too soon, and he was just itching to get back out. This is where his too-many-uber-helpful-and-supportive friends come in.

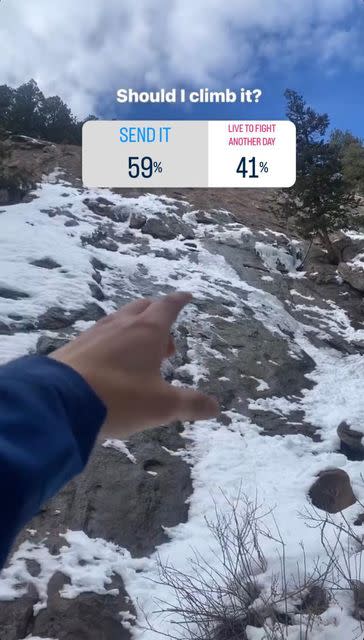

"Flatirons, snowy or dry?" he posted on Instagram as a poll. He texted friends in Boulder, too. He let democracy take the wheel, and the people spoke: The Flatirons were dry. Spotless. He was "good to go." Zach convinced his then boyfriend, John, who was a more experienced climber, to join him in the winter romp.

Of course, you may be thinking, well, didn't they notice once they arrived that the Flatirons were actually covered in snow and ice? Because it was November for crying out loud! Well, yes, they did notice. John tried to convince Zach it wasn't safe. Zach was convinced otherwise. Can you guess who won out? They proceeded.

Zach had hiked up in Vibram's FiveFingers, already a questionable choice in snow. He wore shorts and a Tee. He had a backpack with a windbreaker and, for climbing, a pair of La Sportiva Katana Laces. It was nice, he says, maybe 55 degrees and sunny. They started up the hike around 1 p.m. and began climbing about 20 minutes later.

Despite having to crawl over a few snow patches, they made it pretty far before trouble arose. They had passed the Diving Board--where people make a small leap from one rock to the next and which sits around the two-thirds mark. Zach thought the gnarliest sections of the ascent were behind them. But he was nervous, too.

"You know when you're running through something, and you're like 'Woah, that was close, like, what if I had fallen,' and then you get that in your head and you start panicking?" Zach says that's where he was. If he had been running, he had almost sprained his ankle a few times. But this was no run, and the consequences of a fall would be so much worse than a sprained ankle. So at a junction, Zach veered right for the gutter where John went left. It should have been fine. If the route isn't icy or snowy, you can take either direction and still summit. But again, it was November.

From the gutter, Zach stood on a ledge below a steep blind lip. He pulled up and his heart sank: "It was just like a sheet of ice and snow for, like, the next eight feet," he says. "I tried to clear it off, but the whole thing was just caked." To the right, there was a pile of snow. It didn't look solid, and, says Zach, was possibly filling up a crevice. He wanted to reverse the move, but found that he couldn't--it was blind and there was a stream of ice and water below.

Zach froze. He tried to think rationally, to not panic.

"Yo, what’s going on?" John yelled from above.

There was no getting around it. "I’m stuck, I think," he shouted back. "Can you see anything up there?" John didn't see anything. Luckily, Zach was in a good stance, with two good footholds, a pinch for his left hand and good crimp for his right. He can stay like this forever, right? His time was already ticking.

Let's just breathe, Zach tells himself. Maybe we’re just panicking. We’re fine. We’ve done this climb a million times. 20 minutes pass and he still can't figure it out. He needs to do something.

"Is there anyone we can call to help us?" he finally shouts up.

John called Boulder's Sheriff's department who connected him with Boulder's free, volunteer-based Rocky Mountain Rescue group. Help would come. It was then around 2:30 p.m.

An hour passes. Then another. Zach is shaking violently. His shoes, which had gotten water in them after trudging through snow at the base of the climb, have frozen solid to his feet. It's windy and the sun is long off of the climb. "I was kinda lying to myself," says Zach. He told himself he was fine. He surely thought about the decision to go up in the first place.

"In the history of John and I climbing things, he’s been a lot more precautious," says Zach. "Even in the gym ... [with] a rope and everything, he’ll prefer to do an easier climb to work on technique, whereas I like to try a harder climb that's more physically demanding. I was used to him saying, 'Oh, that seems too hard,' so when he said that about this climb, I was like, 'We’ve done it before. We can totally climb this.'"

Three rescuers arrived around 4:45. Suddenly, a woman rappelled down to Zach. She put a harness on him and attached him to the rope. Zach had begun to experience hypothermia, so she told him they had to keep moving. They hauled him up the wall, and then gave him crampons for the hike down. It was 6:30 or 7:00 by the time Zach made it back to the lot. .

Zach remarked how nice they were. One of the rescuers even talked him into taking a selfie, which he said was a welcome ice breaker from the "Oh my god I'm going to die" tension that had been building. "There was no scolding or like, 'Don’t ever do that again,'" he says.

I spoke with Drew Hildner, public information officer for the Rocky Mountain Rescue Group, which is contracted by the Boulder County Sheriff’s Office. The group routinely provides rescues to climbers in the Flatirons, Eldorado Canyon and Boulder Canyon. Hildner has been volunteering for rescues for the past 20 years.

"Our rescue group is getting busier every year, as are all the other rescue groups in Colorado,” says Hildner. "There [are] a couple [of causes], I think it’s multifactorial," he adds. More people climbing in general is certainly one. It used to be that all the people who soloed the Flatirons knew each other. It was a niche group. Now, a dozen or so soloists can be spied on most fair weather weekends. People go soloing for their lunch breaks. There are competitive car-to-car FKTs.

"Regularly, the people that we are picking off just realize they were emotionally totally unprepared for it, or psychologically unprepared for it," says Hildner. "And from a skill standpoint, there’s some component to that as well, because you can climb 5.10 in the gym all day long and be hanging on huge jugs the whole time. But on the Flatirons, you sometimes might just be pinching a pebble or just gently placing your foot on a little dish. So that can also throw people off as well."

Friction slab climbing is not the same as plastic jug climbing, or even overhung crimping. Seems pretty intuitive, and yet....

Freeway, the route mostly commonly taken up the Second Flatiron--and the route both myself and Zach took--is only rated 5.2. It's almost 1,000 feet of climbing. While most climbers have the skill to solo the Second, fewer climbers understand and appreciate the exposure and the risk. Is there any way to prepare for that, I asked Hildner. Not really, he says. Highball bouldering. Sketchy trad leads maybe.

"Part of getting in the right headspace for free soloing is acknowledging that, when you put your first foot up on the rock, that if you fall, you will die," says Hildner. "That needs to be a very specific acknowledgement that you make in your head, and then that should be the last time you think about it."

Recognize the risk, make peace with it. Don't let the panic set in if something unexpected happens. Zach brought up his experience projecting in the gym. That mind-race feeling when you're pumped, right before you fall or make a mistake. But when you say "Take!" you calm down. You can see what you did wrong and how to self-correct. He said, while you can't 'Take' when you're soloing, you can focus on breathing and letting yourself relax.

Of course, soloing in the first place should strongly be questioned. Hildner says many people that don't belong on the Flatirons end up soloing because of the "expert halo" effect. In other words, when your friend that you want to impress convinces you that it's fine. "It’s that pressure of not wanting to embarrass yourself... by saying you’re afraid, Zach says.

Hildner remarked that the rescue group sees a lot of fatalities in places like Edlorado Canyon, where the walls are steeper. On the Flatirons, he says, gravity is just as inescapable, "but it really beats you up on the way down." Not everyone who falls punches their ticket, but most get severely injured. Significant fractures, head trauma, punctured lungs, pelvic breaks, etc.

"Unique to the Second Flatiron is that the jump off of the Diving Board. We will have people that injure their knees or their ankles or their elbows at that spot." And then, of course, you have to keep soloing.

Hildner strongly recommended climbing the Flatirons on a rope first. Know where the line goes so you don't find yourself off it and potentially on highly technical terrain. "And don’t fall victim to groupthink," he adds.

Zach recommends not going in November. He also said bring a friend. "I think I would have been pretty nervous to have to call the volunteers myself and do everything alone. I think the panic would have set in. ... If I did fall, I would want someone to know immediately." He also wished he'd packed more gear. A proper jacket, maybe.

***

My boyfriend and I also went in November, although on a much less icy weekend. "You got this," he told me. He should have been right, the conditions were cold but OK, and I certainly had the technical skill. But I don't think either one of us expected how risk averse I actually am. We hadn't made it 10 feet up the wall when I bailed to the gutter. I didn't want to make a single move that I couldn't reverse, so I stubbornly climbed the gutter until it ended. And then, right when I could have pulled the lip--the very lip that Zach pulled and then got stuck on--I started the long scoot down.

It doesn't matter how good you are, soloing can still be downright scary. And, as we all know, it's dangerous. I'm not here to tell anyone not to do it, but, I do hope to normalize the fact that not everyone should. Conditions, skillset, experience, and mindset should all be taken into account.

The Rocky Mountain Rescue group is funded by community donations. They’ve answered over 200 calls for lost or injured people this year alone--about 30 of which were for climbers on the Flatirons. Donate or find out how to get involved here. From Zach: Even if you don't think you'll ever need a rescue, you might know someone who does.

Also Read:

Retro-Bolt Snake Dike? Peter Croft, John Long Think So, Others Debate.

Do Climbers Have Expiration Dates? A Lifer Contemplates His Old Age

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.