Inside the Wannsee Conference: how 15 Nazis plotted the most appalling crime in history

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

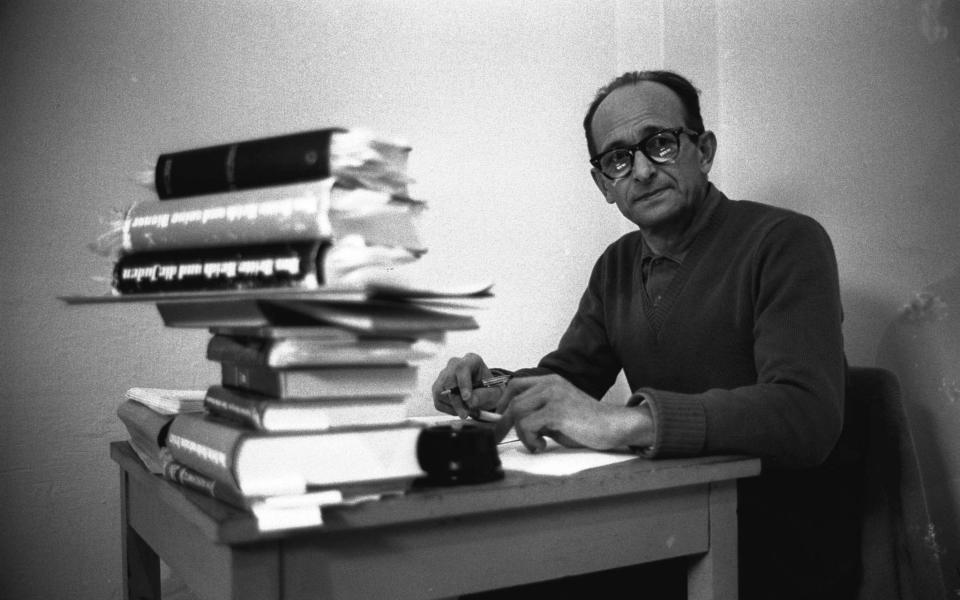

In January 1942 one of the most infamous meetings in history took place in a mansion on the shore of the Wannsee, a lake on the outskirts of Berlin. The 15 men who met at Wannsee were not ignorant thugs – most of them were qualified lawyers, and eight of them held academic doctorates. Yet in this luxurious setting these highly educated individuals would discuss what is arguably the most appalling crime of all time – the extermination of the Jews. We only know about what was discussed at Wannsee because one set of the minutes taken by Adolf Eichmann, who attended the meeting as a Nazi “expert” in Jewish affairs, was discovered after the war.

In the popular consciousness this conference at Wannsee is often thought to be the moment the Holocaust was decided upon. But it wasn’t. As Peter Longerich explains in Wannsee, the meeting was not that decisive, and yet paradoxically the gathering remains hugely significant.

Reinhard Heydrich, the head of the security police and Himmler’s right-hand man in the SS, called the meeting to resolve several key issues. First, he wanted to emphasise that he was in charge of the organisation of what the Nazis euphemistically called the “Final Solution” – a policy that became the extermination of the Jews. Second, he wanted all the various groups involved – like the Foreign Office, the Interior Ministry, and so on – to support the way forward he proposed. And third, he needed to resolve the question of exactly who was to be deported and who wasn’t – were “half Jews”, for instance, to be classed as Jews or Germans?

However, we can be certain that this wasn’t the “moment” the Holocaust was decided upon – partly because selected Jews were already being murdered in the occupied Soviet Union and Poland by the time of the Wannsee Conference, and also because the “solution” Heydrich proposed was not the immediate extermination of all Jews, but something more nuanced. He wanted large numbers of Jews to be deported to the occupied Soviet Union, where they would be forced to build roads. Most of them were expected to die in the process – or, as the minutes put it, “the majority will doubtless succumb to natural wastage”. Heydrich was particularly concerned that any Jews who survived this horrendous experience should be “dealt with accordingly” – code for murdered – because they would, if released, be “the germ cell for a new Jewish regeneration”. So although what was discussed at Wannsee was a plan for genocide, it was a longer term one than the actual Holocaust that followed.

After Heydrich had outlined his proposal, Dr Bühler, representing the area of Nazi-occupied Poland known as the General Government, claimed that the majority of the several million Jews who lived in his region were “unfit for work”. Officials in the General Government, he said, would “welcome” the Jews living there being “removed as quickly as possible”. Bühler and his colleagues, the minutes of the meeting clearly imply, wanted these Jews murdered on a quicker timescale than via Heydrich’s longer-term method of killing.

This exchange between Bühler and Heydrich is significant. It’s an important example of how fluid the Nazis’ search for a “solution” to their self-created “Jewish problem” was. While every Nazi knew the overall vision – that Jews should “disappear” – the practical way of making that happen changed over time. In 1940 the Nazis had even toyed with the idea of deporting millions of Jews to the island of Madagascar, off the coast of Africa, before ditching the plan as impractical. Even if implemented, the Madagascar “solution” would still have been genocidal, as under the rule of a Nazi governor, the Jews would almost certainly have died out in a generation or two. But, once again, it would not have been the Holocaust as we know it.

Because of all this complexity, it’s a difficult intellectual task to place Wannsee in the context of the overall development of the Holocaust. But Longerich – a world-renowned historian of the Nazi period – succeeds brilliantly. He seems to specialise in writing either very long books – such as his scholarly biographies of Himmler and Goebbels – or else quite short ones – like The Unwritten Order, which lays bare Hitler’s culpability for the Holocaust. His book on Wannsee is one of the short ones, but is none the worse for that.

Longerich forensically takes the reader through the origins of the meeting, the biographies of the participants, the minutes themselves, and ends with an explanation of why the killings developed in the months after Wannsee in ways Heydrich had not predicted. By the summer of 1942, for instance, the idea of sending the Jews East to build roads had been abandoned, in favour of transporting them to death camps in Nazi-occupied Poland.

As Longerich reveals, one of the most crucial decision-making moments, post-Wannsee, appears to have been the meetings that Himmler held with Hitler in the spring of 1942. It was only after these discussions that the Holocaust moved into its last murderous phase. Wannsee is thus best understood as an important milestone along the winding road that led to the murder of six million Jews, rather than the single moment of decision. Skilfully translated from the original German by Lesley Sharpe and Jeremy Noakes, Longerich’s Wannsee is a masterful crash-course on the decision-making process of the Holocaust.

Wannsee is published by OUP at £20. To order your copy for £16.99, call 0944 871 1514 or visit the Telegraph Bookshop