Inside Tory Burch’s Lovingly Restored Antigua Getaway

Inside Tory Burch’s Lovingly Restored Antigua Getaway

Sittings Editor: Miranda Brooks.

The Plot Thickens

Made in The Shade

Island in The Sun

Bloom-Bloom Room

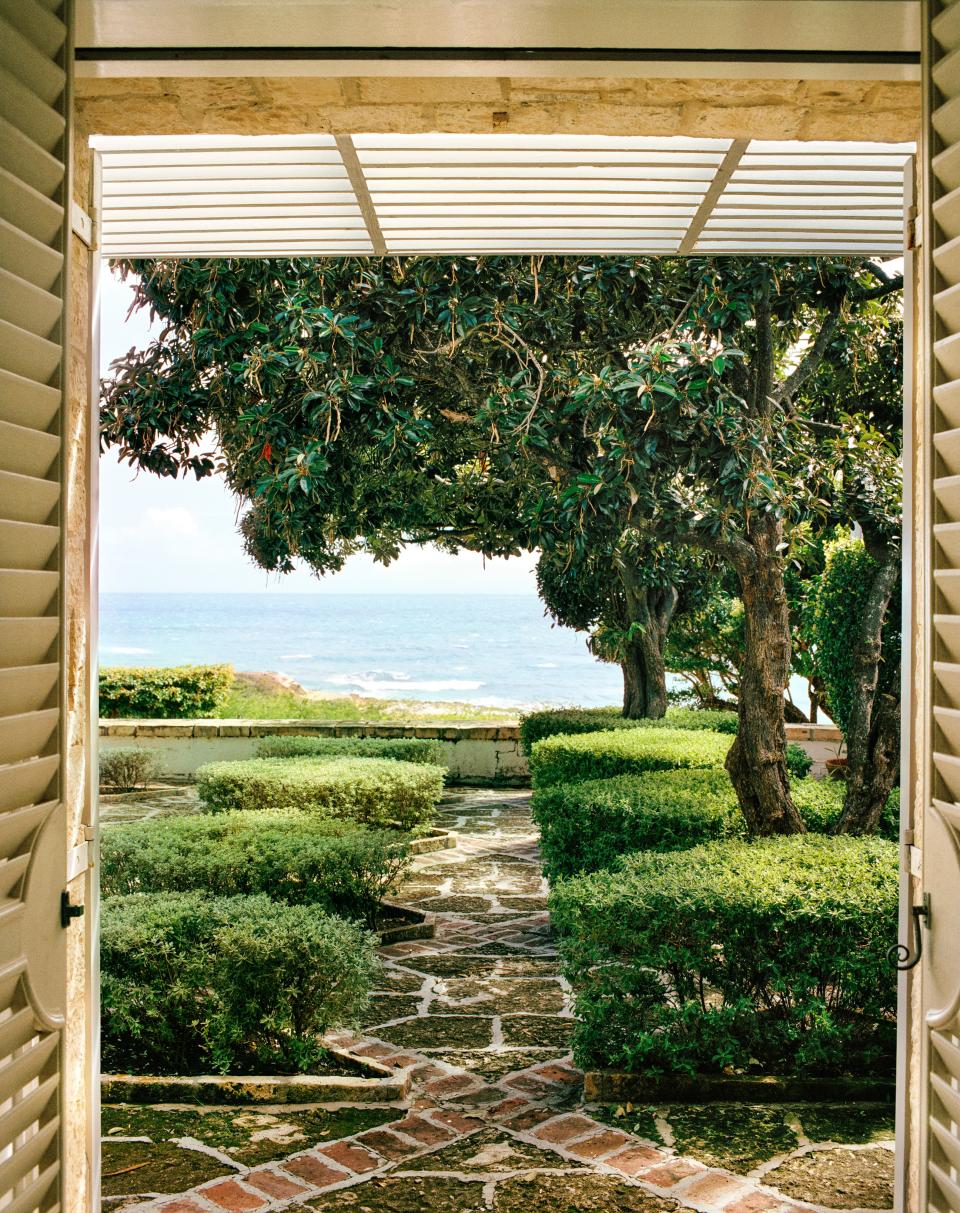

The Mellow Brick Road

Field of Dreams

At the cusp of the 1960s, the legendary tastemaker, gardener, and cultural philanthropist Rachel “Bunny” Mellon acquired a handsome plot of land that hovers over an azure bay on the Caribbean island of Antigua. Here the architect H. Page Cross created a series of elegant pavilions decorated by Mellon with the celebrated Billy Baldwin. Although unrestrained by finances, Mellon’s perfectionism was subtle: She instructed one of her designers to make the items that graced the interior look as though they had been brought “down from the attic.” But she also insisted that imperfect potato chips be removed from their bowls. “It plays at unpretentiousness,” wrote Vogue staffer Alison Harwood in an effusively enthusiastic report on the house to then editor Diana Vreeland, “pretending to be as casual as the blue denim wrap-around skirt and matching floppy-brimmed cloche devised for Mrs. Mellon’s working costume by Mainbocher.”

The furniture for the house was slipcovered in D. D. Tillett’s hand-printed cottons, and the canopy beds were hung with Madeleine Porthault’s flowered sheets. The silvered shingles of the roofs were made from Brazilian wood, the terraces underfoot hewn from coral stone. Oak floors were scrubbed with salt water to age them, and then painted to imitate stone paving, like those in Swedish country mansions. The pathways that trellised the fragrant herb garden outside the chatelaine’s bedroom and in the far-flung potager were made from bricks imported by the British, who used them as ballast for their ships. (They sailed home with rum.) Mellon also nurtured local craftspeople, who created the handmade clay pots and the rustic wattle fencing, and established a carpentry workshop that could replicate antique furniture. (It’s still flourishing.)

When they were all done, Baldwin called it “the prettiest house in the world,” and Mellon herself declared that it was “the house I love the most”—and she had an impressive array to choose from. Mellon led a relatively sequestered life here—the widowed Jacqueline Kennedy and her young family, as well as Hubert de Givenchy, who had a dedicated suite and his own china and linens, were among the few guests. As she reached her centenary, however, Mellon retreated to her estate in Virginia, and the property was put on the market, where it languished for years.

Tory Burch wasn’t looking for a Caribbean home, but she had always been intrigued by Mellon’s taste and by the dashing stylemakers of the 1960s—in fact, when she founded her self-titled line in 2004, Burch looked to the vintage country club wardrobes of her glamorous parents for inspiration, and her fall 2018 collection is partly inspired by her friend Lee Radziwill’s “effortless style.” As it happens, one of Burch’s childhood friends had a house near Mellon’s, and during a family Christmas in Mustique, plans were laid for a visit—“just for the heck of it,” as Burch remembers. The beauty stunned her—and to her great surprise, her three sons (Sawyer, seventeen, and twins Henry and Nick, 20) loved it too.

But the house had barely been lived in for 20 years.“The gardens were dead,” says Burch. “The trees were dying.” Her fiancé, Pierre-Yves Roussel, special adviser to Bernard Arnault, the chairman and CEO of LVMH, also had reservations about the rehabilitation of the property. “The bones were all there, but it definitely had a lot of wear and tear,” Burch recalls. “I had to convince him, but we decided it was something we wanted to do together.” They plan to wed on the property before the end of the year.

Burch was determined to be respectful of Mellon’s imprint. “How do you perfect someone’s taste when that person has perfect taste?” queries Burch. “I wanted to pay homage to her, but make it our own as well.” She called on her friend and longtime accomplice the architect-decorator Daniel Romualdez, who has worked on her rambling 1929 Gatsby manse in Southampton and her apartment at the storied Pierre hotel, and has crafted the dynamic David Hicks–ian interiors for her stores and showrooms around the world. “He understands about that restraint and shabbiness,” says Burch, “the idea of imperfection—like washing out fabrics to make them look old.”

“The layout that Page Cross did is pretty hard to mess with,” adds Romualdez. “We didn’t really touch it.” The house is, indeed, simply impeccable. Cross designed the rooms to flow into one another, with shuttered French windows revealing vistas at every turn. The plumbago-blue dining room opens on one side to a tropical conservatory, paneled in pale lime-green bamboo, where hummingbirds purr over orchid plants, banana fronds, and palms. Below, a meadow of soft gold wild grass sways in the wind like the bay’s eddying waters.

Alterations were thoughtfully considered: The bathrooms were subtly updated and a pantry added to the kitchen, where gingerbread shelving now houses Burch’s early–nineteenth century botanical china—some of it from Mellon herself, the rest sleuthed online. On Romualdez’s advice, a guest house was transformed into a “man cave” for Burch’s and Roussel’s sons (he also has three). “If I didn’t have it,” Burch notes wryly, “it would be a bit of a nightmare.”

Burch found antique French provincial furniture in the auction rooms and in her parents’ basement and mixed it with the wicker seating from furniture-maker Bonacina that Italian style icon Marella Agnelli used in her own fabled humble-grand schemes. “Our goal,” Romualdez explains, “is that you can’t tell what the interventions are.”

Vogue Contributing Editor Miranda Brooks, meanwhile, was charged with bringing the gardens back to life. She chose flowers that come into their own at dusk, when the unforgiving sun has cooled, the moonflowers open up, and the vanilla bush, Panama rose, and almond trees are at their most fragrant. There are heady scents everywhere—a reflecting pool is filled with yellow water lilies; combined with the licorice-scented oleander and the pale-yellow frangipani, it is almost overwhelming. (“Will you tell Estée Lauder we want to do a frangipani?” Burch, ever pragmatic, instructs an associate.) “Miranda has great vision,” says Burch. “And she was channeling Mrs. Mellon: It’s almost a spiritual thing. What she did was amazing because it looked like it had always been there.”

Inside and out, Burch’s goal has been to make the house sustainable and ecologically responsible. There are solar panels, a desalination plant, and a cistern to collect the rainwater that holds half a million gallons. (The broader caretaking imperative extends to her work as well: Since the company’s founding fourteen years ago, the philanthropic arm, the Tory Burch Foundation, with Bank of America as a partner, has given out $40 million in low-interest capital loans to help female entrepreneurs.)

In the vegetable garden, Burch gleefully points out the serried ranks of okra, eggplant, beans, peppers, kale, cucumber, and cantaloupe. Mellon went on foraging trips round the island with her gardeners, transplanting plants to her property. “It’s the only way to do it,” says Brooks: Many imports are prohibited because of the potential that they will bring disease. There are papaya trees in the orchard and macadamia trees in the nuttery, and against the odds, Brooks has even managed to create a flourishing rose garden. “The gardens will always be a work in progress,” says Burch, “but the imperfections are so beautiful.”