Inside Photographer Tyler Mitchell’s Radical Vision of Personal Style

Why is it so hard to take a great fashion photograph?

To start, there’s just the logistical challenge, says Tyler Mitchell, the 25-year-old wunderkind who became the first Black photographer to shoot a Vogue cover when he captured a flower-crowned Beyoncé in 2018. “It’s a real fine game of negotiating needs in a fashion commission,” Mitchell said in a recent Zoom call from London, where he is living for the summer, “because the function of an editorial is to please advertisers. That’s why it was designed, and that’s why it was invented. There’re mind games you have to play.”

But making a great fashion picture also poses a larger existential query. For the past ten years, as Instagram made images both a global language and currency, and digital media seemed to edge out print, commercial fashion photography felt in some ways stuck in a rut: head-to-toe runway looks, shot on a static model, often captured in midair. Mitchell is part of a new generation of Black photographers—first codified in GQ contributor Antwaun Sargent’s 2019 monograph The New Black Vanguard—including Dana Scruggs, Micaiah Carter, Nadine Ijewere, and others, who are imbuing a new life into fashion photography.

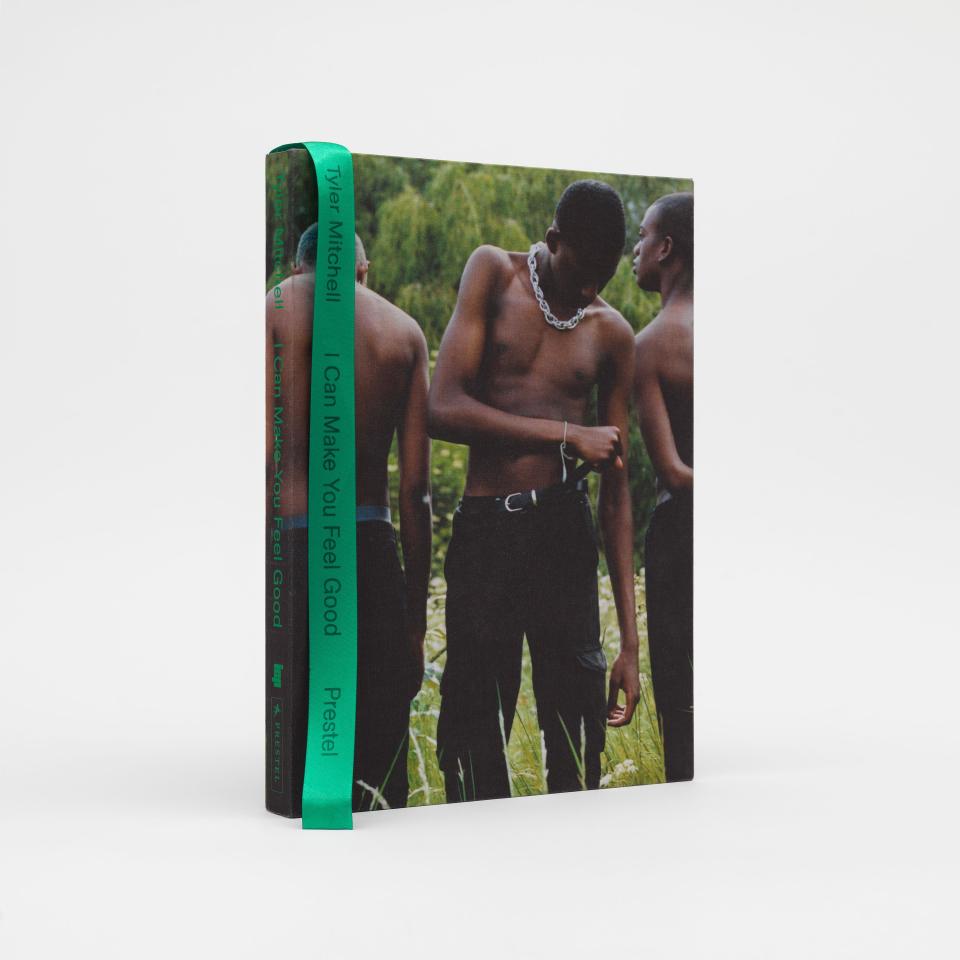

Next week, Mitchell releases I Can Make You Feel Good, a book of photographs first exhibited in a 2019 show of the same name that demonstrate the ambition of his vision of Black figures in relaxation. “It’s about proposing a future,” Mitchell said. “It’s about suggesting the idea that visualizing Black bodies enjoying leisure time, and just existing as they want to be, is a very special thing when you think about denied histories.”

Mitchell, who also captured Kanye West for the GQ’s May cover, first honed his eye on Tumblr. The impact of that platform’s endless waterfall of imagery—its refusal to distinguish between fine art and vernacular, its divorcing of decades and fads from chronology—is evident on his work. Photographs conjure the macrame curtained interiors of a midcentury Harlem home as easily as they summon the flaneur physicality of skateboarding. “All that's floated in there,” Mitchell said, “and it’s meant to present the breath of beauty and dignity of the Black experience.”

Mitchell studied filmmaking at New York University, and grew up particularly admiring the work of photographers like Ryan McGinley and Larry Clark, both of whom advanced the provocative meld of fashion and art photography that was first established in the 1970s and ’80s by photographers like Helmut Newton, Deborah Turbeville, Richard Avedon, and Guy Bourdin. Mitchell recalls coming across a book Clark created for Jonathan Anderson’s eponymous brand in 2015: “It’s this whole day of them just running around Paris together,” he said. He liked how it rejected the cold commercial eye of other contemporary advertising and editorial. “It was something that was fashion,” Mitchell said, “but it wasn't overtly fashion, at least to my eyes as a newcomer to that world.”

What makes Mitchell’s images, and those of this new generation of photographers, so powerful are their majestically intimate representations of Black people, who weren’t often in the kinds of images he grew up admiring on Tumblr. In a period where the larger fashion industry is still struggling to shake its attachment to a white Eurocentric fantasy, Mitchell’s images signal a new concept of utopia, one where Black bodies relaxing, playing, and enjoying themselves are a manifestation of luxury.

The shift Mitchell signals is aesthetic as well as representational. As fashion has become a global phenomenon over the past 15 years, with millions tuning into watch fashion show livestreams and celebrities becoming something like high-fashion interpreters, clothes have become frustratingly two-dimensional, flat objects engaged with through a screen. (Rei Kawakubo memorably tweaked the idea in her Fall 2012 Comme des Garcons collection.) Elsewhere, the evolution of the stylist into a celebrity and dealmaker has made fashion something to be placed on the body rather than a vessel for expression: clothing is borrowed for an evening and literally put on a figure, the look the result of an entire team and an agenda in pursuit of a single photograph to be widely circulated. Many of the clothes we’ve seen on celebrities or talked about on social media over the past decade are not meant for living in. Personal style has been overshadowed by the carefully calculated and curated image in the quest to make fashion a keystone of pop culture.

Mitchell’s images provide a welcome, human alternative. They epitomize the covenant of body and cloth that defines style and, over time, come to create biography. A boy with a dripping pink ice cream cone wears a slubby polo that feels sensuously textural, lived in, sweated in. Two men on skateboards, their arms locked together, wear knitwear and denim with the easy shagginess of true skaters.

One photograph shows a shirtless man swinging from beneath, his jeans slung low. “You really feel the sense of this boy breaking out of whatever kind of psychic shackles may exist,” Mitchell said, in large part because of his exposed back. He took a cue from McGinley, who often photographs shirtless youths: “As much as clothes and fashion play a role, it’s also the removal of those and the importance of being free and breaking out of those symbolically is important.”

Black men have long been a driving force in fashion and style, but they were long pushed to the fringe. Now it seems that through photographers like Mitchell; designers like Grace Wales Bonner, Telfar, and Pyer Moss; and musicians like Young Thug and Lil Uzi Vert, Black masculinity is at the center of fashion and culture. “For me, there have been several revelations,” Mitchell said. “Living inside [my] Black male body, this is something that I move through the world and experience every day. So there are certain things that I couldn’t tell you because I’m inside my body, and this is my life, and I'm speaking about autobiographical experience.”

Still, Mitchell registers a watershed in the broader understanding of Black masculinity, sparked for him by Barry Jenkins’s 2016 film Moonlight. “The conversation that that movie sparked, I think, was a revelation for me and for the world. Beyond that, when we think about the wider cultural implications of how folks view Black men, it’s just past time. It’s past due to revise those old world understandings of Black men and their bodies. I think there’s just been this large push en masse across a lot of art forms to revise what that looks like and to understand more widely that a Black man is what a black man is. A Black man dresses however that Black man dresses, and that has nothing to do with any of these kinds of stereotypes.”

I Can Make You Feel Good: Tyler Mitchell

$60.00, Bookshop

Originally Appeared on GQ