Inside the Movement to Bring the Arts to Outer Space

I’m on the moon. Or on a floor on the moon. Actually, on a metal floor in a space analog building in the desert where I am simulating, with three other people, being on the moon. We’re here to imagine space, keep house, and make art. We’re calling it Imagination 1. With me are three of my University of Arizona colleagues: poet and archivist Julie Swarstad Johnson, dancer and choreographer Elizabeth George, and textiles artist and costume designer Ivy Wahome.

We’re spending a week here, and though we are above ground, I’ve been thinking about caves—how we’ve made light and dark both markers of time and places of residence.

Once, at the Deutsches Museum in Munich, I wandered among exhibits and dioramas: a tiny figurine on the edge of a model Grand Canyon, a water mill, many kinds of engines. Most captivating was the cave at Altamira, a faux-rock replica of the now-closed prehistoric site in Spain, a grotto with paintings of deer, horses, and bison, fashioned from black and ochre pigments. The originals are at least 19,000 years old, but, like the long-dead artists of Altamira, the museum painter used manganese and charcoal. Dark animals muscled across the rock relief. They curved and rippled. We take lineage with us: this time, rocket fire to the Moon and the animal bodies of meaning.

The gradually accumulating evidence that water ice lurks in the permanently shadowed regions of the lunar south pole has inspired a renaissance of science and exploration—and, in the not-so distant future, perhaps the extraction of that ice for water, air, and fuel. NASA’s Artemis 2 will fly by the Moon at the end of 2025. Perhaps as soon as late 2026, the first woman and the first person of color will land on the Moon and begin again our human ventures there. The Apollo missions, all told, only spent a couple of weeks on the lunar surface. In just one mission, the Artemis 3 explorers will stay for about a week. The hope is that this human presence won’t be one-off boot prints in the powdery lunar regolith—that eventually, there will be habitats, base camps, even villages of a kind.

We take culture with us, even to—especially to—space. Astronauts watch movies, play music, and sing songs on the International Space Station. While I've not been to space, I once lived for a month in a tent on the polar plateau of Antarctica. I watched The Simpsons and listened to everything from Bach to The Mutton Birds. That was comforting.

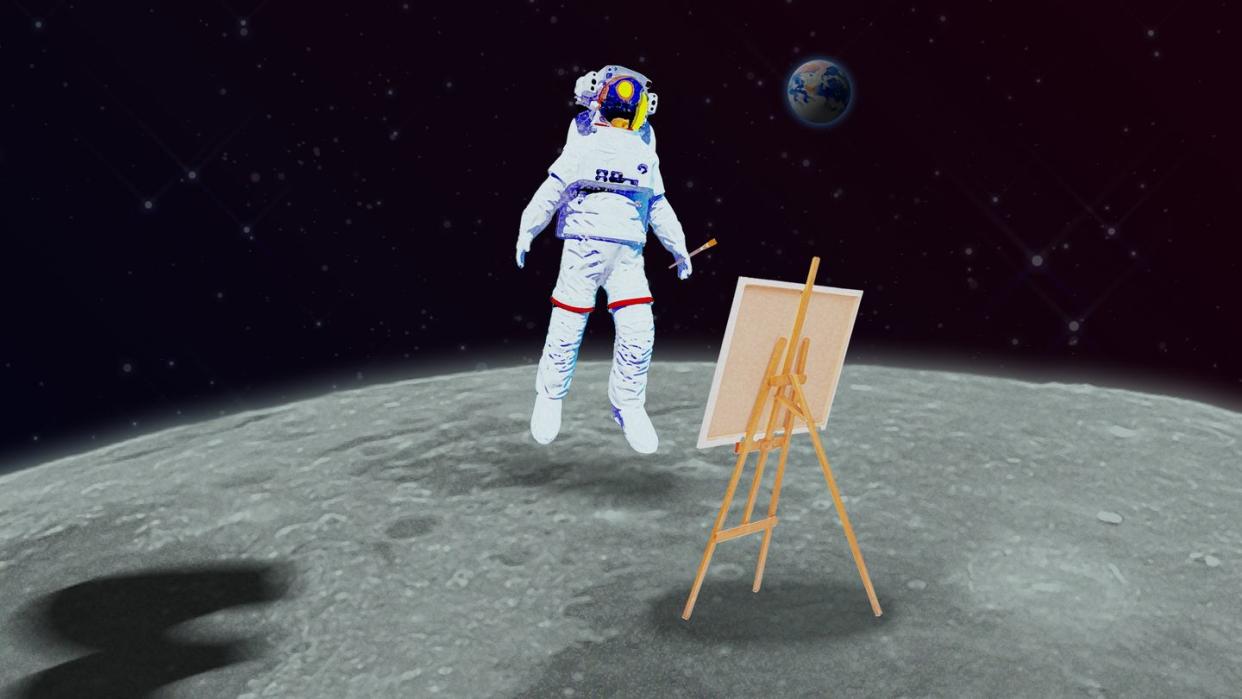

But in extreme environments like space, we should demand more than just enjoyment. The very things said from and about the Moon can be strengthened with artistic technique. How we render the Moon will either replicate our worst tendencies on Earth or foster a respect for the time-worn beauty of this companion world. From simulating living in a lunar habitat to talking with astronauts who will fly around the Moon next year, I am obsessed with investigating how we can return to the Moon to live and work while using the tools artists know. Because those tools can help make life worth living.

Before my own lunar mission, I kept thinking that art was like an airlock: a transition that moves us from one world to another. That still seems right. But the metaphor misses something. An airlock is for safety. Art isn’t.

Despite the long history of art and exploration working together (not always for good ends), and despite the existential importance of artistic expression, there remains in the space community a real opposition to the argument that the arts matter as much as, oh, high-pressure flow dynamics in liquid-fuel rocket-staging. The abiding divide between the humanities and the sciences—what C.P. Snow famously called "the two cultures"—is alive and well in this arena.

But many human endeavors are creative. We make things, from equations to the latching mechanism on an airlock door. Yet the leaping that happens when we create art—the connections across time and distance—that’s different. Those connections can foster an expansive, sometimes dizzying humility. That's a form of celestial navigation. We can reach the Moon without it, but, if we do, we'll be lost.

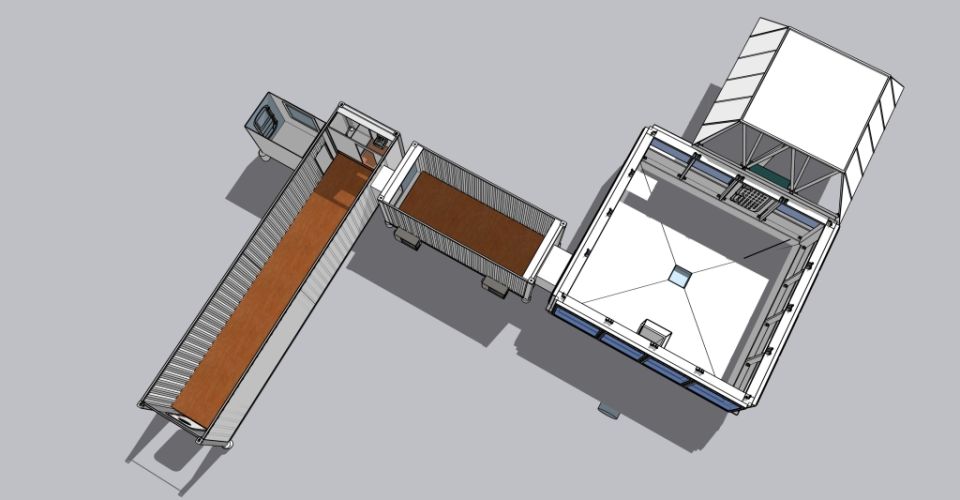

If our simulated lunar mission was truly Altamira 2.0, we would have stayed in a cave. Instead, Julie, Liz, Ivy, and I set up shop in a pressurized habitat called the Space Analog for Moon and Mars (SAM) near the iconic Biosphere 2 (B2), a massive structure which in 1991 hosted humans for a two-year sealed mission, as though on a spaceflight. In fact, part of our habitat, the Test Module (TM), was the one-room prototype of the giant space-frame B2.

On the Moon, the first permanent dwellings won't be on the surface, like ours, but, according to many scientists, they’ll be clusters of cozy buildings snugged inside ancient lava tubes: vacant, subsurface passages where the basalt roof remains, but the lava has gone. Altamira 2.0. Such a lunar lava tube provides a skylight for entry and exit, and protection from the blistering heat and cracking cold, not to mention cosmic rays and meteorites. We go to space to return to our subterranean origins.

To get Imagination 1 off the ground, we worked with Kai Staats, the polymath visionary behind SAM. About two years ago, he started renovation of the Test Module (abandoned once the tests were done before the two-year mission) by literally digging out rat shit with his colleague Trent Tresch. It was in a conversation with Kai that I mentioned the possibility of an all-artists mission at SAM. With funding from the College of Fine Arts and other units at the University of Arizona, I was able to make it happen.

At some 1200 square feet, SAM contains an airlock, bathroom, kitchen, crew quarters, and an engineering bay that opens up to the original Test Module, which now holds a hydroponic rack and work stations. Down a small ladder on the TM’s south side is a crawl-through tunnel—about 2.5 feet in diameter and 13 feet long—that leads to “the Lung.” The Lung is like a mechanical diaphragm weighing nearly 4000 pounds that pushes down the air beneath it, creating a steady pressure inside SAM that’s higher than the atmosphere outside. While such a system would be pointless on the Moon or Mars (neither have significant atmospheres), it’s the most physically impressive mechanical system at SAM. At 29 feet in diameter, the Lung is a circular room that looks like an outtake from Tarkovsky’s Solaris.

After we entered, we properly pressurized the habitat, the giant diaphragm of the Lung lifting slowly toward its ceiling and reaching the desired elevation.

Because SAM does not yet have a projector system or photographic prints to cover windows with pictures of my beloved Moon, we all avoided looking outside at the desert landscape. I closed my eyes to see the black-and-gray-and-white-and-sometimes-blue-sometimes-faint-pollen-yellow of the Moon’s surface, places I know by heart from my years of lunar telescopic observing.

At night, the windows grew dark as a lunar cave. I slept on a floor pad under a shelf in the Engineering Bay while the women occupied the Crew Quarters. Against the bright grow lights of the hydroponics visible from the pass-through to the TM, I wore an eye mask. Against the whir of a refrigerator and the thumping of the water pump, headphones.

Daily, we used the hydroponic greens at lunch and dinner, making stews and soups with dehydrated lentils, beans, tomatoes, and corn. In the morning, we breakfasted on oatmeal and instant coffee. And we talked, like friends at a campfire. We cleaned up. We checked systems. Half the work of exploration is the work of domesticity.

Each day, we dispersed like mindful molecules in a sealed vat.

Early on in the mission, Julie went to the windowless Engineering Bay to 3D print a mission phrase, “Frontier or Heartland.” Later in the mission, she sat in the airlock with a notebook, writing a poem that, in part, reads:

Anywhere we go, the body must be fed

and held against something, rock or the motion

of endless falling, metal or the sound

another human makes while working

needle through fabric, thought across time’s

finest length. Anywhere we go, the mind

will fall inward through the distance…

Ivy worked in the spacious TM, where on a metal work table she set up a sewing machine. Everywhere in the TM were bright fabrics and designs. She used a childhood blanket from Kenya on which to sew a tapestry—a symbolic mission log of sorts. She sewed on footprints drawn from our feet, a thickened hemisphere representing the Moon, silhouettes of cacti, astronauts, and more.

“I have vivid memories of falling asleep with this very blanket looking up at the Moon from my bedroom window,” she told me. “Besides, if I was to really go to the Moon, I would want to take something sentimental to me.”

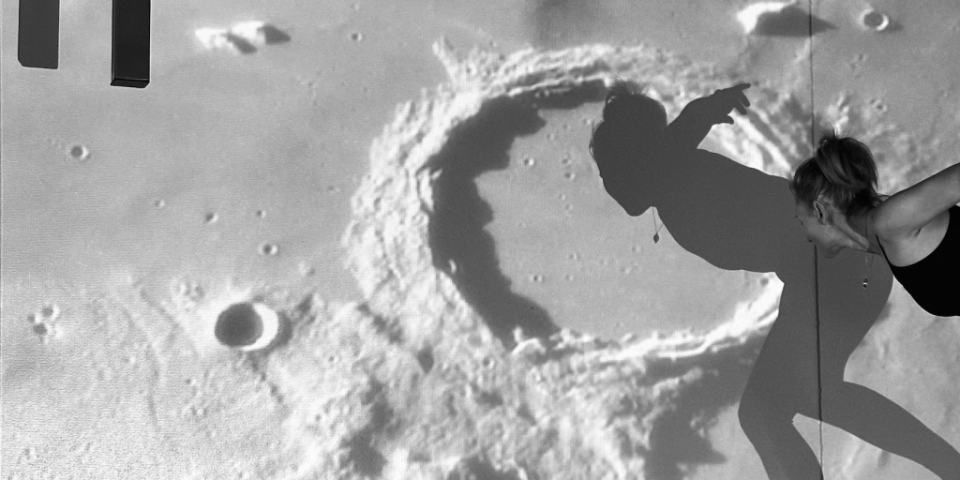

Liz wrote and edited video clips in the Crew Quarters, sitting on her sleeping pad, but mostly she resided in the Lung, where she slid, lifted, and lunged to the strains of “Moon River.” All week, she thought about “ballon,” she told me. “It’s the quality of ‘light-footedness’ in a dancer's jumps. To appear weightless, suspended in space and connect with that ‘light space.’ The imagery of a balloon bouncing in space came to mind often as I was moving both in the habitat and on the rig.”

The rig was, as I would see up close outside of the habitat, a long, sleek counter-weight system to simulate lunar gravity. We would each take a turn on it as though walking on the Moon.

Me, I turned the shelf beside the 3D printer into a standing desk to write about the Moon I know and the possible houses of the lunar future. I tried out metaphors with less precision than the mouths that blew ochre onto Altamira’s walls. Because I could only see the sublime Moon in my mind and in pictures, I gave my eye to the metal walls, the bolts, and the sensors that feed “SIMOC,” the software that monitored the environment here. The red lines of CO2 levels traced in different reds like the lines of a heart monitor.

The first humans to orbit the Moon did not find the lunar surface much of an inspiration. Apollo 8’s James Lovell told Earthlings, “Okay, Houston. The Moon is essentially gray, no color; looks like plaster of Paris or sort of a grayish beach sand.” Crewmate Bill Anders would also liken the “boring” Moon to “dirty beach sand.” Commander Frank Borman said, “My own impression is that [the Moon is] a vast, lonely, forbidding-type existence, or expanse of nothing, that looks rather like clouds and clouds of pumice stone.”

In the NASA transcript, someone has inserted a commentary: “Jim’s impressions of what he sees… are honest, [but] they predate NASA’s emphasis on science and geology that led to later commanders, Jim included, becoming accomplished field geologists themselves and enthusiasts of what the Moon’s landscape has to offer. Perhaps as a consequence, his portrayal of the lunar surface as gray and colorless set a tone for the public’s subsequent perception of the Moon as uninteresting.”

Those later commanders included Dave Scott of Apollo 15. He and fellow Moonwalker Jim Irwin and Command Module Pilot Al Worden embraced the study of geology for the first and still most fruitful human scientific expedition to another world. During their 17 field trips in just over a year, the crew became geologists. That training helped them see the Moon as a home.

Scott admits in his memoir, Two Sides of the Moon, “In the beginning, we had little idea of what was expected of us. When asked to describe what I saw on one of the first trips… I got not much further than saying, ‘Boy, there’s a lot of stuff on the other side of the hill.’ Soon we were describing… granite, basalt, sandstone, or conglomerate, and its shape as angular, sub-angular, or rounded.” But time was of the essence: “We had to make instant analyses, and decisions on the scientific value, of the objects we found, without the time to relish their meaning,” Scott recalled. He later likened the Moon to “an exhibition of exquisite images by the great photographer Ansel Adams.”

If the crew did not have the capacity to bridge their enthusiastic abstractions—spectacular, mind-boggling, beautiful—with their exacting geological details—angles of slope, placement of clasts, numbers of lineations—they show us that with additional grounding in metaphor, astronauts have a chance to be artistic communicators while they are over and on the Moon. The next lunar astronauts don't need to be English professors like me. But a little understanding of metaphor—oh, like little engines of perspective—can help the next lunar explorers convey the Moon in ways that will guide attitudes and actions. Put another way, a metaphor can be a crystalized zeitgeist.

The Moon as home and catalyst. Metaphor as quest and convergence.

I was the last to make a Moonwalk. On day five of our mission, I sat in a camp chair while the space suit that Julie had just used aired out. I would don it soon.

During Liz’s excursion the day before, she danced as though she were on the Moon. She reported that sense of “ballon” as she did slow spirals down from leaps, possible only in lower gravity, real or simulated on the rig. The films I saw of Liz dancing in the 1/6th equivalent of Earth’s gravity made me dream of Artemis astronauts taking lessons from Imagination 1’s dancer: suited pirouettes beside core-sample drills.

Then Ivy used an awl to sew, even though the pressure suit gloves made it a struggle to grip the thread. “I got the hang of it after two tries,” she told me. ”If I had to try it again, I would find a way to get the thread slightly weighted with a tape—like the end of a shoe lace—to make it easier to thread it through. I think it’s very possible to sew on the Moon.”

Julie said that her stamp asking “Frontier or Heartland?” was a lunar take on letterpress printing. ”Part of why I love letterpress printing is the physicality—it's just you, the type, and the press,” she said. “I always take a deep breath before I pull a print, and I did so today as well before I pulled up the stamp from the regolith.” She had just completed the task before my turn.

I am not someone comfortable with confinement or heat, but as I looked at my checklist for the last of the arts EVAs, I felt, well, I felt aware.

“Okay,” I said, “let’s do this.”

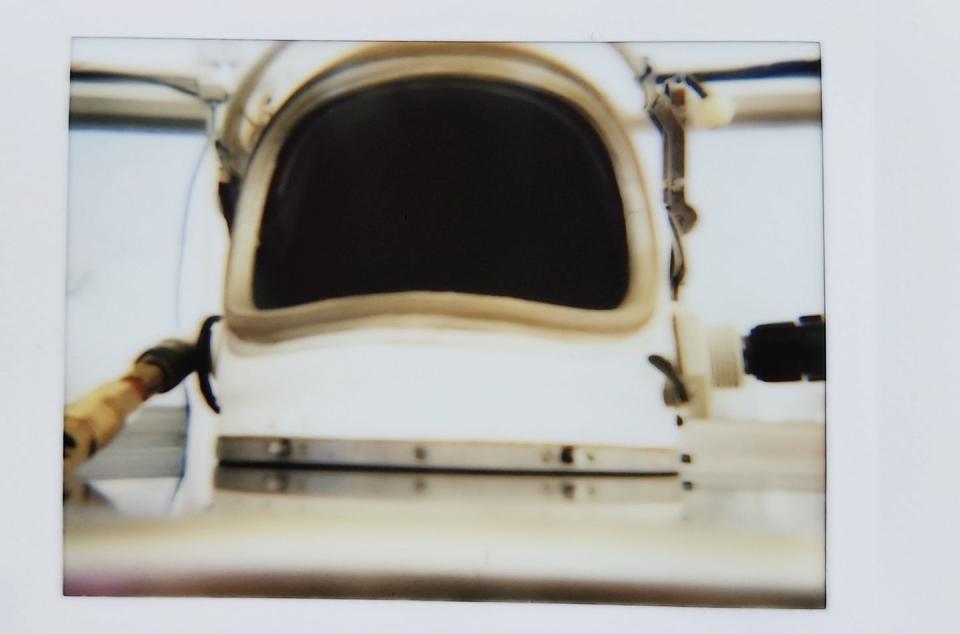

I walked into the airlock in tights, a sweatband, and a loose shirt like the lead singer of a local ‘80s cover band. While Ivy and Julie helped me don the bulky pressure suit, Liz held a fan up to blow air across my face.

For the EVAs, the crew that stayed inside used walkie-talkies. Kai, Trent, and Matthias Beach (another SAM staffer) were outside, waiting, as my crewmates closed the interior airlock door and sealed its vent shut. Pulling myself up against the bulk of the suit (it’s like wearing a small car), I opened the exterior door’s vent and watched the pressure drop on the wall-mounted gauge. When it was safe, I lifted the red hatch, opened the door, and stepped outside to shockingly cool air. Trent checked the suit, talked over hand signals (no radio in the suit), then lowered the helmet over my head.

Its own world, that plastic globe locked into the neck ring. The air, coming from an umbilical attached to a compressor in the Test Module, hissed by the right side of my mouth.

The off-set rig features a safety harness, to which Trent and Matthias fitted me. Above, a rail ran 50 feet long and 12 feet high with counterweights to loft me once I was hooked to the system. When the harness lifted me up, I was floating, slightly, as on the Moon, even though I was really in a covered industrial-like yard.

The gravity rig was breathtaking, sometimes literally. The bite of the crotch harness reminded me of the system making this illusion possible, but I focused on steps, on body control, that slightly awkward, sometimes graceful touch in the “walking.” The whole body became involved. I imagined the real Moonwalkers, imagined doing this for seven hours, their stiff arms and sore legs, their long checklists and short time. I found a forward-leaning gait, tip-toes then throwing the body back, digging in the heels to stop.

I walked down and back twice; then, from a pouch Ivy had made, I took a Lomography Automat instant camera to photograph the dark “regolith” where Julie had stamped her question. Pressing the on button while turning the focus ring took several seconds. The glove’s fingertips were huge, like stiff versions of my thickest winter gloves. Finally, it came on.

The prints ejected like flat passengers emerging from a ship.

In those moments, I was briefly lunar. I’ll never get to the Moon now except through my telescope, but if I did, it would feel a bit like this. And I would want to write it, to speak it.

While some astronauts have gone on to write poetry (Al Worden, Story Musgrave) and become visual artists (Alan Bean, Alexi Leonov, Nicole Stott), no agency training anywhere involves creative communication using the techniques artists use all the time, such as association, contrast, and figuration. Former astronaut Mike Massimino explained to me that NASA gives its astronauts a strong grounding in public speaking and story-telling (Massimino’s results on “The Moth” speak for themselves). But, according to then-astronaut Alvin Drew, it didn’t bridge the gap. In 2016, he said, "Seeing things that we weren’t ever evolved enough to go experience, and not having the words to convey that to somebody so I can give them that same experience, was very frustrating."

Only one human has gone to the Moon with formal training in the arts: Apollo 12 Moonwalker Alan Bean, who took art classes while he was a test pilot in the 1960s. When he returned from the Moon, he painted beautiful work of that exploration. How marvelous it would have been if he had done so while in space.

The task-driven nature of our time in SAM and on the EVAs has given me pause. Is it fair to ask the astronauts to be engineers, house-keepers, teammates, scientists, pilots, technicians, and artists, too? No. Yet ask we must, for how we imagine and communicate the Moon will go a long way in shaping how we treat it—like a frontier merely to be exploited for its water ice, or a heartland to be stewarded?

Former astronaut Nicole Stott isn’t sure she would have thought about packing a watercolor kit before her first space flight in 2009. But a friend suggested it, and Stott told me, “Painting in space was one of the personal highlights of my spaceflight.” When I asked her about giving astronauts workshops in the arts, she agreed, “It would be a nice option.” But she also emphasized, “Astronauts have been bringing their creativity with them since the very first human spaceflights—even without encouragement.”

From the Voyager Golden Records to poet laureate Ada Limon's “In Praise of Mystery: A Poem for Europa,” missions have been sending artwork to space for decades. The Moon, too, has become a gallery space: the Apollo 12 mission secretly carried tiny artistic stamps created by Andy Warhol and others on a hidden tile, while the Apollo 15 Moonwalkers left a placard with the names of dead space explorers along with a metal figurine called “The Fallen Astronaut.” Today, artwork continues to make its way to the Moon. The Intuitive Machines craft that landed in early 2024 (the first U.S. vessel to land on the Moon since Apollo 17) featured in its payload rack a series of metal bearings representing the Moon, sculpted by multi-millionaire artist Jeff Koons. Another arts payload, MoonArk, didn’t touch down when the commercial lander carrying it failed to get there. MoonArk, a conceptually brilliant and democratic project spearheaded at Carnegie Mellon University, may send another in the future; meanwhile, the Europe-based Moon Gallery is seeking support for sending artworks on a lander. Also plotting a creative excursion to the Moon are the members of the #dearMoon mission, a billionaire-funded lunar-orbital project planning to use SpaceX’s Starship to send some celebrity artist influencers there and back. The voyage has yet to be scheduled, as Starship is needed first and foremost for NASA’s Artemis missions.

Artemis 2 isn’t carrying any artworks, at least so far, but it is set to launch with the most media-savvy and friendly crew ever to travel in space: Commander Reid Wiseman, Pilot Victor Glover, Payload Specialist Christina Koch, and Canadian astronaut and Mission Specialist Jeremy Hansen.

When I spoke with Glover, it was with both poetry and the Moon in mind. Glover has made a point of talking about his engagement with—and sharing of—Gil Scott-Heron’s famous 1970 spoken word poem, “Whitey on the Moon,” a searing critique of prioritizing space exploration over social justice.

He also cites Marvin Gaye’s “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler),” which protests, “Rockets, moon shots/Spend it on the have nots/Money, we make it/’Fore we see it you take it.” Our interview, he said, inspired him to think about a “lunar listening tour” with people around the world, so that the crew can gain an even deeper appreciation of the cultural importance of the Moon. “Because we are the humans who get to do it,” he told me. “And it's very important that we don't come across with a colonization mindset.” In fact, he and his crewmates added the word “sustainably” to the NASA tag-line of “going back to the Moon.”

Glover says of Artemis 2, “It's not just about the first non-American to go to the Moon, the first Black person, and the first woman. The developing world doesn't have a rocket ship of its own. They are still going with us because we really do want to make this feel good for all people.” Glover’s sense of the Moon-for-all crucially includes “the power of ancient wisdom.” As he explained, “It's the idea that advanced technology is only one of the tools that we're using. It’s the thousands of years of collective history. Our total story is a part of why we're going and what we're taking with us.”

Canadian Space Agency astronaut Jeremy Hansen will be bringing a story of Indigenous wisdom represented by his personal mission patch. (Non-American NASA astronauts have personal mission patches because they fly less frequently than Americans). Anishinaabe artist Henry Guimond, with input from Dave “Sabe” Courchene III, head of the Turtle Lodge in Sagkeeng First Nation in what is now Manitoba, created the patch in collaboration with Hansen. It contains rich symbolism, like the bow representing the Greek goddess Artemis, and, less obviously, a “thin blue line” emblematic of the life-force in all creatures. While arising from one First Nations culture, the design nonetheless contains universal themes, from love to respect.

What stories will each astronaut tell as the Orion capsule loops around the Moon, sending humans farther than anyone has ever traveled? (Hansen notes that the task-crammed nine-day mission will include 12 public affairs events.) What will Glover say? Glover’s love of poetry and song will surely inform that moment. “I will do everything that I can to make this a journey for all people,” he said. “It's going to be our stories that are going to last for a while to get us to the next mission.”

One thing that will help Glover, I think, is that his interest in the Moon extends beyond “a scientific perspective.” He has a telescope, though he told me, “I don’t use [it] as much as I should.” He does look at pictures of the Moon frequently. “I stare at the Moon a ton,” he said.

Glover intuits, I think, what the conservationist Aldo Leopold once said: “Our ability to perceive quality in nature begins, as in art, with the pretty.” That sounds possibly trivializing. But Leopold continues: this ability “expands through successive stages of the beautiful to values as yet uncaptured by language.” The ability to perceive can also become an ability to communicate, with values perhaps indeed captured by language. So why not empower astronauts to communicate with the tools and techniques of artists? After all, chance favors the prepared mind.

As the engineer William Bezouska put it in a 2021 policy paper, “The world abounds with tangible examples of this spirit in the work that connects art and space… organizations that seek to identify and foster these connections may find benefits across the spectrum of space activity while at the same time supporting one of the most fundamental human activities: creating art.”

It’s unlikely that NASA will see its way clear any time soon to offering even the briefest workshops in, say, slant rhyme and tapestry design. But the stakes couldn’t be higher: today’s astronauts are going to set the tone for our first steps in becoming multi-planetary. Training in the arts will not only ease their struggle to describe the wild, majestic Moon, but it will convey to the rest of us what the lunar heartland can and should be.

If creatives can’t fly to the Moon (not yet, anyway), we can help those who are to tell the stories they need to tell, to craft the metaphors that will surprise and provoke, and to be as ready as they can be for the images they can share through the lens, on a canvas, and in poems. Shuttle astronaut Story Musgrave, who came back from space to take a literature degree, puts it this way: “Poetry can provide anyone with an additional and powerful way to capture and communicate any and all human experiences.” That includes being in space, or on the Moon.

Art is ancient wisdom, and it’s wedded to the manifold complexity of our lunar future: one in which some humans will be living and working on the Moon. One in which most of us will look at the fat, white-orange orb rising on the horizon and know that others of us are there.

Once, in Turkey, at a meeting of the Association of Space Explorers, a fellow astronaut beckoned Glover over. “He grabs me around the shoulders and walks me out,” Glover said, to see a break in the clouds, “an opening… the Moon is hanging right there in the sky.” Glover’s colleague said, “'I just want you to come back and tell me what it feels like.’”

On the last night of Imagination 1, Julie set up a projector in the Lung with photos of the Moon curved and huge, as though we were there. I went down the short ladder from the TM, crawled through the tunnel, and leaned against the cold wall. There was the narrowest mountain range on the Moon—Montes Agricola beside the Aristarchus Plateau. There was an image of craters at the lunar south pole, striations visible across all of them: the ejecta of an impact. There were the dark, blistered Marius Hills.

I felt as though I were in orbit, looking through a massive window, and I remembered countless evenings in backyards with my telescope. I wondered how connected to the Moon its future residents will be. Time has been on the Moon longer than we have been on Earth. We need crafted constraint and artful openness. Data and metaphor and threads and graceful movements. It was big, the Moon in the Lung, and I had no easy thoughts that night as I finally rose to crawl back to my sleeping pad.

I hope that when Victor Glover tells us what it feels like—when they all do—it will be with language both fresh and metaphoric: words rippling across the dark like painted figures from an ancient cave, messages to and from our different homes.

Parts of this piece are adapted from Still as Bright: An Illuminating History of the Moon, from Antiquity to Tomorrow by Christopher Cokinos, with permission from Pegasus Books.

You Might Also Like