Inside the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts's Thierry Mugler Retrospective

While the rarity and exclusivity of the works add cachet, what makes the exhibit special is how it presents the totality of Mugler's work as art, rather than fashion.

Thierry Mugler is not a designer. "There's already an important distinction between a designer and a couturier," says Nathalie Bondil, director general and chief curator of the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts. "But Mugler is an artist."

I, for one, had never been a big fan of Mugler's work; I'd personally found the garments to be either unwearable or a tad too garish. So, I approached "Thierry Mugler: Couturissime," the exhibition put on by Bondil's MMFA, with hesitation — out of both curiosity and obligation. What was so spectacular about the show that could draw the likes of Kim Kardashian West and Tyra Banks to a cold, snow-swept Montreal in late February?

The answer became increasingly obvious as I walked through the exhibit, which does a tremendous job of framing Mugler's work as encompassing more than fashion; it presents him as a true artist who excelled at creating a fantastical, transhumanist universe through the oeuvre d’art totale — total artwork.

"Thierry Mugler: Couturissime" was curated by Thierry-Maxime Loriot, who first made a name for himself in curatorial circles with the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts' hugely successful touring exhibition on Jean-Paul Gaultier, which originated in 2011. Since then, Loriot has become one of the world's foremost experts at the intersection of fashion and art, working with Viktor & Rolf, among others. So highly regarded are Loriot and the MMFA when it comes to fashion exhibitions that Mugler — a notoriously private man who's turned down multiple overtures from other museums over the years — specifically approached them for this.

Mugler appears to have made a sage decision: More than 150 looks, produced over 40 years (from 1977 to 2014) are on show, most of which are being exhibited for the first time. Sprinkled throughout are sketches by Mugler — again, many previously unseen — alongside more than 100 photographs by the likes of Karl Lagerfeld (the print arrived at the museum the day that he died, Loriot told me), David LaChapelle, Steven Meisel, Mert and Marcus, Inez and Vinoodh, Ellen von Unwerth, Helmut Newton and Guy Bourdain.

Quantitatively, it's what one might expect from a museum exhibit, but it's the quality of the works on display that stands out. That, and the fact that most pieces being exhibited are exceedingly rare. Mugler, as mentioned above, has been reticent when it comes to exhibits and has granted few interviews. Bondil frequently says that "it's easier to see a Picasso in person than a haute couture dress" and, among haute couture artisans, Mugler's work is especially hard to come by. The prints from the Helmut Newton Foundation are the first to ever be lent out to a museum in the history of the Foundation. Costumes on rotating three-month loans also represent an exceptional breach of protocol for the Comédie-Française, who have rarely, if ever, collaborated with museums. As Loriot, the curator, put it: "It is a coup for the museum" and a "true world premiere."

That exclusivity has made the exhibit all the more popular. "Security is freaking out," Loriot admitted, before offering an impressive rough estimate of 10,000 visitors over the first two days. The exhibition has already been booked to appear at the Kunsthal Rotterdam in late 2019 and at the Kunsthalle Der Hypo-Kulturstiftung in Munich in 2020; additional stops will be announced, I am told.

While the rarity and exclusivity of the works add cachet, what makes the exhibit special is how it presents the totality of Mugler's work — as art, rather than fashion. "Mugler never followed trends," Loriot notes, adding that it's "the Mugler universe as a whole" that's interesting to look at. As such, the exhibition is divided into acts, much like an opera.

It opens dramatically, in a dark room filled with Mugler's work for the Comédie-Française's 1985 adaption of "La tragédie de Macbeth": seven costumes, a few dozen sketches and a holographic display by Michel Lemieux. It's the museum equivalent of a cold open. "You don't expect to start with Shakespeare," says Loriot, "but I didn't want to start with the 'powerful women' cliché [so often associated with Mugler's work]."

While perhaps unexpected, it is certainly effective, offering a clever bit of foreshadowing: Mugler's fashion is very much performative, from the silhouettes to the textiles to the runway shows to the campaigns. It also introduces us to the Mugler silhouette of almost-cartoonish proportions.

That flows seamlessly into an examination of Mugler's singular ability to transform fashion into spectacle — to stage fashion, as Loriot puts it. Photos of Madonna and David Bowie wearing his creations grace the walls, with more contemporary references to Lady Gaga, Cardi B and Beyoncé scattered throughout. At the back of the gallery, George Michael's "Too Funky" plays on a loop. The famous "Too Funky" bike outfit is on display (above), as are some of the other ready-to-wear pieces that were eventually purchased by performers and became stage costumes. It is a showcase of Mugler's star power—and explanation of why he became, arguably, the signature show-stealing couturier of the '80s and '90s.

Equally important to the glitz and glamor, though, was Mugler's ability to create stunning visuals for his clothes. A sombre gallery is filled with Mugler's life timeline and with dramatic photographs taken by him for campaigns. That is followed by a bright, white gallery filled with black-and-white photographs captured by Newton, who became Mugler's foremost collaborator — it was Newton who pushed Mugler to take up photography, frustrated by his desire to control every aspect of their first shoot. Mugler was painstakingly involved in every aspect of his brand, from ideation to presentation, and these two galleries offer a glimpse at the important role that photography played in presenting his creations.

Mugler's many extracurricular creative endeavors are also highlighted in this portion of the exhibition. He was a trained dancer before taking up fashion design; there was the aforementioned photography; he designed costumes for theatre productions and for the iconic Parisian club Le Palace; and he made his directorial debut in 1985 with the short film "L'antimentale" and went on to write, produce and direct music clips, advertisements and other short films. In fact, such was Mugler's multi-disciplinary genius that he left fashion altogether in 2002 to focus on his other creative pursuits. Walking through the gallery, Virgil Abloh and Hedi Slimane come to mind as contemporary designers who exhibit similar patterns.

Loriot, for one, scoffs at the comparison. "Nobody has [truly] done what Mugler did," he says. "He was the first to shoot his own campaigns. He was a pioneer [when it comes to being a polymath.]" But, more importantly in Loriot's eyes, today's designers, be it Abloh or Slimane, are multi-disciplinary because it's trendy, whereas "Mugler [did it] because he was a control freak."

If the first part of the exhibit focuses on Mugler's guile for creating a riveting universe for his clothing — and curating every last detail — then the latter part is focused on the relationship between clothes and the human body in Mugler's world.

The first gallery in the tail end of the exhibition is split in two, divided into black and white, with jewel mobiles hanging from the ceiling. On display are some of Mugler's most notable "glamazon" looks. The decidedly Muglerian bulging shoulders and tiny corseted waists are crucial to any examination of Mugler's work. Still, Loriot's curation brings a new dimension to the fore: The pieces on display are predominantly black and made from latex, lace and PVC — femininity with a dash of dominatrix and bondage.

The exhibit closes with two galleries centered on transhumanism. Act V is dedicated to Mugler's work with insects and animals, with particular emphasis placed on his Spring/Summer 1989 "Les Atlantes," Spring/Summer 1997 "Les Insectes" and Autumn/Winter 1997-1998 "La Chimère" collections. Some of the most impressive works are found in this portion of the exhibit — but they're also some of the least wearable. The designer's penchant for the fantastical — which is, understandably, what Loriot has emphasized for the general public — may actually distract from some of the more technically advanced pieces, the ones that enrapture those from the fashion world. Case in point: an almost surreally delicate blouson made of twine from Mugler's Spring/Summer 1999 "Les Tranchés" collection. Loriot and I both considered this piece to be the most stunning in the exhibit, but it gets somewhat lost in the immersive gallery designed by the Oscar and Emmy-winning special effects firm RodeoFX.

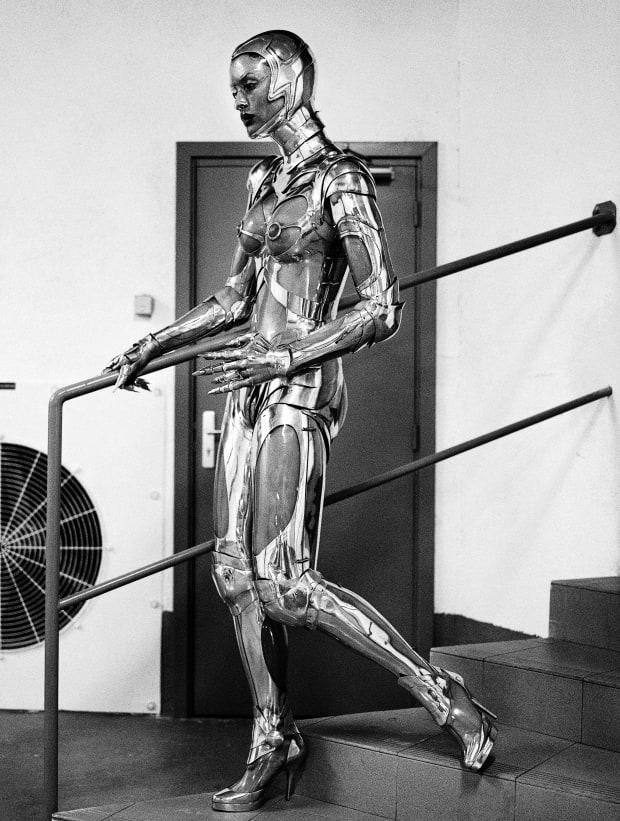

Last but not least, Act VI focuses on Mugler's obsession with the clothes of the future, spanning from his Spring/Summer 1979 "Sirène Galactique" collection to his work on "The Wyld" in 2014. His Autumn/Winter 1995 metal and PVC Maschinenmensch outfit figures prominently — with the exhibit calling it his masterpiece — as does its precursor, from the Spring/Summer 1991 "Diana Ross, Superstar" collection.

The transhumanist subjects, the robots, insects and animals "are the most spectacular pieces," per Loriot. In fact, he argues that there's an unspoken agreement in fashion circles that nobody should ever touch those three subjects, because Mugler has captured them so perfectly. "To revisit them would be a crime," he says.

Ending with such a spectacular display was important for Loriot, whose main challenge in a digital age is getting people to actually visit the exhibitions. It was also deeply personal for the curator and for Phillip Fürhofer, who was responsible for the layout of the last gallery; both have dealt with heart problems at relatively young ages. Loriot confided that "it was therapeutic for two young men who had heart problems — you don't survive heart problems at my age — to work together on this vision about how the body could be reliant on technology and be beautiful."

That idea — beautifying the body through clothing and technology — is at the core of what "Thierry Mugler: Couturissime" highlights. The exhibition does not counter the argument that Mugler's designs are unwearable for the average person. They are intricately crafted from materials (like PVC, rubber or twine) that, at the time, were never used in the couture world. It is a work of stunning, awesome beauty — especially when taking a wider look at what Mugler achieved.

Stars, magazines and the world's leading photographers continue to be drawn to Mugler's work. The aforementioned maschinenmensch looks have featured in recent spreads, two decades after their creation. "I don't know any pieces in fashion history that are still photographed like Mugler's robots are," says Loriot, "Everybody has shot them. Everybody has worn them." Kim Kardashian West, Cardi B, Lady Gaga, Céline Dion and Beyoncé have all worn Mugler, whether vintage or made specifically for them. In fact, one gets the feeling while walking through the exhibition that Mugler has never been more relevant.

Much of that owes to the fact that contemporary designers tend to eschew the risks that Mugler took. "Mugler, [Jean-Paul] Gaultier and Rei Kawakubo,belong to a category of creators that doesn't exist anymore," Loriot tells me, "[they] belonged to a category that invented things and were trying things."

Would the business people running brands today sign off on Mugler's ideas? Probably not. "Mugler's exit from fashion was very much tied to the changing economic landscape of the industry," Bondil explained. In the early 2000s, when Mugler stepped away, large conglomerates, like Gucci Group (now Kering) or LVMH were wielding increasing power and placing more emphasis on profitability, rather than on pure creativity. Mugler, in many respects, represents the antithesis of consumer-driven fast fashion. He was an artist who used fashion as a medium.

That, if nothing else, is the resounding message one is left with at the end of "Thierry Mugler: Couturissime": Mugler was not a designer, nor was he like other couturiers.

"Pierre Bergé [Yves Saint-Laurent's longtime business partner] once told me that he didn't know if couture was an art form," recounts Bondil, the MMFA director, "but he knew that it took an artist to make couture." And Mugler was definitely an artist.