Inside the Making of Frank Sinatra's Star-Studded Comeback Album

After the 1984 release of the album LA Is My Lady, with Quincy Jones, Frank took a break from recording. A long break. He continued to travel and perform in concerts, but for the greater part of a decade, he wasn’t sure he wanted to go back into a studio. During those years off from recording, he liked to watch the late-night talk shows. Talk-show hosts like Johnny Carson or Dave Letterman were always asking performers, “Who was influential in your career? Who did you listen to?”

He’d hear performer after performer saying, “Well, Sinatra was the quintessential singer, and this particular song, it’s one of my favorites…” So, Frank kept hearing performers say how they were fans of his and talk about their favorite Sinatra songs. Eventually, he started asking himself, What if I paired with so-and-so on their favorite song? The initial idea of doing the Duets albums came from Frank himself. Duetting on an album would give Frank a chance to do one of his favorite things: perform with another singer. By then, though, Frank was in his late seventies, and he wasn’t sure Reprise would be interested in doing another album with him. The last album he’d done for Reprise was Trilogy in 1980.

Frank told Jilly [Rizzo] one night, “This whole duet thing I’ve been thinking about, I like the idea. I’m liking the way it sounds. But the prospect of doing another album for Reprise, the way they’ve been handling my stuff, I’m not so sure.” He left it at that. What he didn’t say was that this would probably be the last thing he was ever going to record, and he wanted it to be good.

After decades with Frank, Jilly knew how to interpret Frank’s meaning when he said something. The unspoken words Jilly heard were, Why don’t you look into it for me, because I don’t want to make a formal inquiry and then put myself in a position of being embarrassed by what I hear back. Frank wanted to find out how Mo Ostin, the head of Reprise, would feel about Frank’s going in and doing another record, and he wanted Jilly to test the waters. So, Jilly made an appointment with Mo, and I took him over to Warner Bros., because at that point Warner had already bought a portion of Reprise. When Jilly came out of the meeting, he didn’t say anything about what went down, and I didn’t ask, but he clearly had something on his mind.

We were driving back down the hill to my condo when Jilly said, “I can’t believe the attitude that Mo just gave me.”

“What do you mean?”

Jilly told me that Ostin had said, “I think the world of Frank. I appreciate everything he’s done for me, but I think Frank’s recording years are behind him.”

Neither I nor Jilly told Frank what had happened. Shortly after that meeting, Jilly passed away, and I sure didn’t have the heart to tell Frank about the meeting with Mo. Fortunately, Charles Koppelman, the head of Capitol Records and EMI was already interested in re-signing Frank with Capitol. Koppelman presented him with a picture that was very appealing. Frank said Charles told him, “Well, you pretty much started your career at Capitol. What better way to close out your career than coming back home to Capitol?” So, Frank made the transition and signed a very sweet deal with Capitol, with a blue-chip royalty fee and substantial back-end payments if the record was successful.

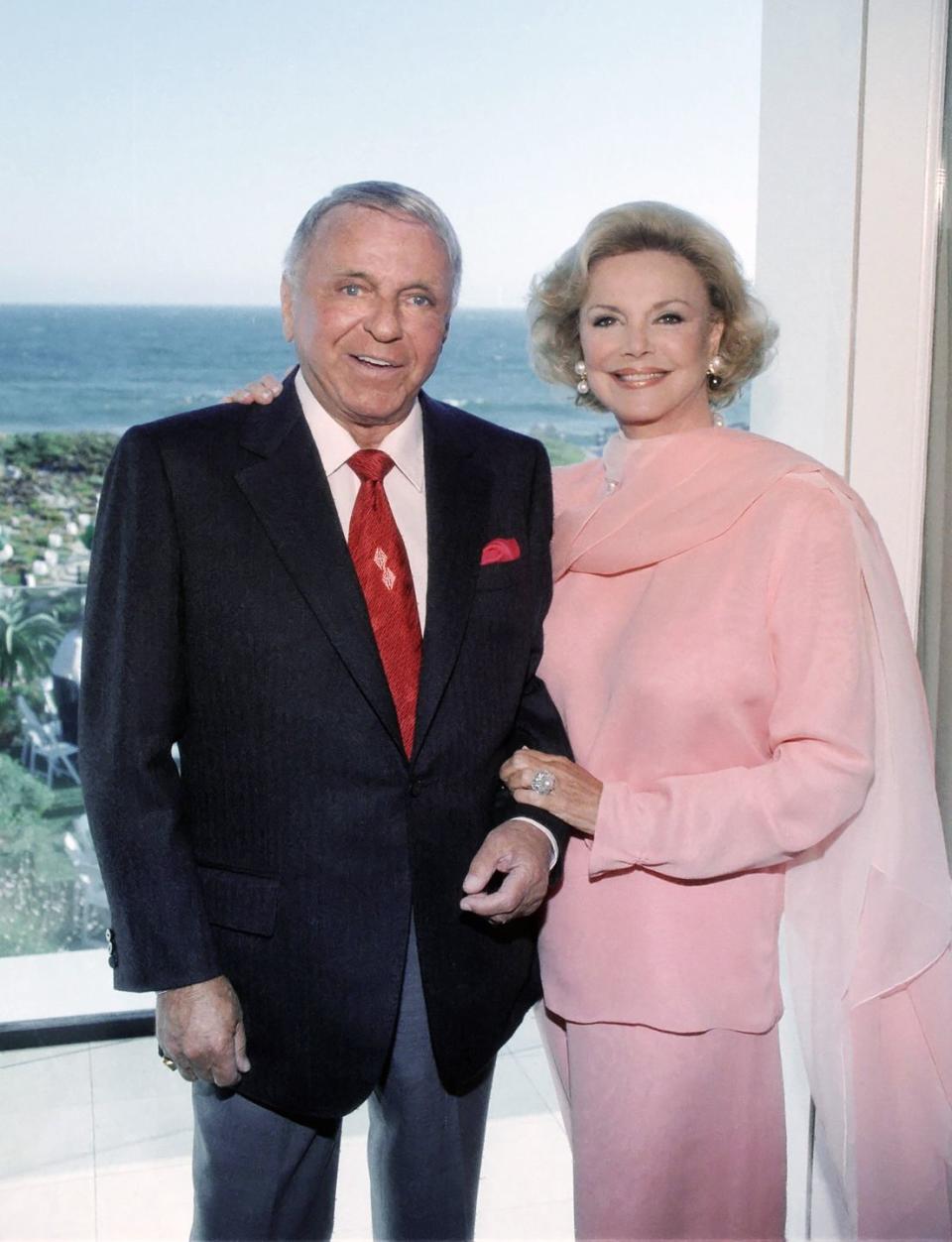

When the announcement that Frank was going back to Capitol Records was made in the press, he got a telegram from Mo Ostin, saying, “I’m very disappointed you never even inquired about doing this at Reprise. And I’m very disappointed personally.” Frank felt terrible. We were in the desert when the telegram came. It was late, and Barbara had gone to bed hours earlier, but Frank and I were still up. After listening to Frank beat himself up over it for a while, I couldn’t take it anymore.

I said, “I got something I need to tell you. Jilly couldn’t bring himself to tell you because he didn’t want to piss you off, and he didn’t want you to be hurt. But now that I’m hearing this, I have to tell you. Jilly went to see Mo about a possible deal for you on this duets thing. Jilly said that Mo basically told him that your recording years are behind you.”

Frank looked at me. “Oh, really? Oh, really?” That did it. Frank did a complete turnaround and never looked back. Reprise’s loss was Capitol’s gain.

So, Duets was a go. But when they started to look into the whole thing, it became clear that Frank wouldn’t be able to do the album the way he’d envisioned. We were in Vegas with Hank Cattaneo, Frank’s production manager, at Frank’s suite in the Desert Inn. Hank was one of the producers on the record, and he told Frank that because of scheduling conflicts with other artists, it wasn’t possible to put Frank in the studio recording live with the other singers. Frank would likely be in the studio by himself, laying down his tracks. Then the duet portion would be put together in post-production.

Frank balked. He told Hank, “It’s not going to come out right. You cannot duplicate the energy you get between artists when you do something right there in the moment, live. That’s why I recorded live with a studio orchestra, and I’m in the middle of it on every single record I’ve ever done.” He was starting to get really worked up.

Finally, I looked over at Hank and said, “Let me jump in here.” Then I turned to Frank and said, “I understand what you’re feeling, Frank, but let me tell you the way most performers record these days. Very few record live with the band there. These performers are accustomed to doing records in pieces. They go in, and they record the rhythm section, and then they go in two weeks later and do the brass and the woodwinds, and eventually, they stand in an isolation booth and lay down the vocals. That’s the way most artists are accustomed to recording these days. So, picture this: You’re asking these people to come into the legendary Studio A of Capitol Records with a live fifty-plus-piece orchestra and then look across the room and see your face. You know what you’re going to get? Dust.” He looked at me a second, and I could see a smile kind of creep over his face. So I continued, “What Hank’s telling you is extremely possible.”

“I don’t know, T.”

“Frank, you remember when we were in the desert a couple of weeks ago, we were sitting out by the pool, and we were listening to the radio? And that gorgeous recording came on, ‘Unforgettable,’ with Natalie Cole?”

“Oh yeah, what a great record.”

“What year is this?”

“Don’t be funny.”

“How long has Nat King Cole been dead?”

“Holy shit, that’s right. If they could put her voice with a dead guy…”

“Exactly. It can be done.”

Frank thought for a moment and then said, “Okay, you made your point.” He still wasn’t crazy about the idea, but I convinced him it was possible.

Once Frank was on board, the people who were involved came up with a tentative list of singers they wanted to have on the album with Frank. Frank had only limited control over the singers he duetted with. He would have loved to record with the people he’d sung with over the years. Frank wanted to do “Mack the Knife” with Ella Fitzgerald. At the time we were doing Duets, though, Ella had just had her leg amputated because of her diabetes. She lived only a few blocks away from Frank. I told producer Phil Ramone, “People are recording their portions all over the world, and she’s right down the street. There’s nothing wrong with her throat, and there’s nothing wrong with her voice. I think this actually might be a major plus for her, given what she’s going through.” He agreed with me that Ella would be ideal, but he thought her health was too fragile to risk it. The executives wanted more current performers, people who’d be a draw for younger audiences. They lined up Jimmy Buffett to do “Mack” with Frank. No disrespect to the man—Jimmy Buffett is good at what he does—but “Mack the Knife” isn’t really his style.

Thirteen people were eventually signed to duet with Frank on the first album. Capitol had no trouble finding people eager to sing with Frank. Once performers were approached as potential duet artists, they’d submit a list of their favorite Sinatra songs. The songs were then cross-referenced, and that’s how the producers figured out who’d do what. Frank would lay down his tracks first. Then Frank’s voice would be removed, and the duet voice plugged in, and the couple paired.

The first night we were due to record was a disaster. It was a Monday. I drove Frank to the studio, along with one of the executive producers, Eliot Weisman. As we walked down the hall of Studio A, Frank’s tension was obvious. When we got to the studio, we saw that the orchestra was in one part of the studio, and an isolation booth was set up for Frank in another part.

Frank said hello to everybody, then said, “Where do you have me?” They pointed to the isolation booth, and Frank said, “Wrong.”

Several of us huddled together, and I said, “Listen, he’s not comfortable unless he’s in the room with the band.”

Then Frank turned around and looked at me and motioned with his index finger. “Let’s go.” And we left. The producers were panicked. The evening had cost them a load of money, with a full complement of musicians and engineers who had to be paid, whether Frank sang or not.

The next night, I drove Frank to the studio again. I didn’t know what to expect. They had made some changes to the layout overnight. They now had Frank set up in a semi-isolation booth off to the side of the room. They’d put up baffles (padded portable walls with sound insulation), creating a four-by-eight soundproof structure. In the middle of it was a window that Frank could look through and see the orchestra. Frank still wasn’t happy. He came back to where I was waiting in his dressing room and started getting himself all worked up.

I said, “Listen, relax. But you know what, Frank? The guys have been here rehearsing, and we didn’t do anything last night. I think it would help the musicians to phrase what’s written if they know where you’re going to put your voice. Then if you really want to split, we’ll get out of here.” I knew Frank had a soft spot for his musicians. Most were guys who had recorded with Frank from the late ’50s on.

Frank finally said, “Okay.”

At that point, I’d started to wonder whether the problem was really all about the isolation booth. Frank hadn’t recorded anything of substance in almost eight years, and I knew how he felt about things that were laid down for eternity. Knowing that this was probably the last recording he was ever going to make, he didn’t want it to be embarrassing. What crossed my mind was, He’s afraid he can’t do it anymore. So, I figured, okay, if he can hear what he sounds like, maybe he’ll be all right.

I went out and said to one of the sound guys on the sly, “Listen, I only got him to do one or two scratch vocals, and I need you to do me a favor. Plug something into the board so that I can have a recording of it. And don’t tell anybody.” He nodded.

Frank came out and ran through a few tunes with the orchestra, and then he wanted to leave.

He said, “Okay, we’ll see you soon, fellas.” Once again, people in the control booth were looking like at us like, Holy shit. Oh, my God, he’s leaving again, and we’ve got nothing.

As we were walking out, I saw the guy I’d talked to in the control booth. He glanced around, then handed me a cassette he’d made on a Dictaphone. I murmured, “I’ll meet up with you later. I don’t want anyone to have any evidence of this, and I don’t want to get you in trouble.”

The next day, Wednesday, there was no recording session. The producers tried to figure out what to do next. That afternoon at lunch, Frank and I were sitting by the pool, and as usual, we had the little portable boom box (radio/cassette player) that we used to take outside with us. We were listening to music on KMPC when Frank went in the house to get a cigarette. As soon as he left, I stuck the cassette of the scratch recording in the boom box and cranked the volume down a little bit. When Frank came out, I hit “Play.” He lit his cigarette and sat down again next to the boom box. I waited. I knew I was taking a big risk. Frank might be really angry about what I’d done, something that had never happened with us before.

He took a drag and all of a sudden got this weird look on his face. “What the hell is that?” Then, “Turn that up.”

I turned it up, and he said, “When the hell did I record this?”

“More important, do you like the way you sound?”

“Well, yeah, it sounds pretty good. Why?”

“Well . . .”

“You did that?” Then it dawned on him. He smiled and shook his head. “You son of a bitch.”

I said, “Frank, do you like the way it sounds? It’s raw, not mixed, and no effects, but I think you still sound pretty damn good.”

“Roll it back to the top.” I ran the thing back and played it for him in its entirety. He looked at me with this big smile on his face. “When’s the next recording session?”

“Tomorrow night if you want.”

“They better be ready. Because if I get mine, they better get theirs.” Ol’ Blue Eyes was back.

Thursday night, I drove him to the studio again. We went in, Frank said his hellos, and we looked at the new arrangement of Studio A. They had reconfigured his isolation booth again, and he was as close to being in the middle of the band as possible without the band’s bare stuff bleeding into his microphone. It was as close to what he was used to as he was going to get. Frank was okay with it. You could practically hear the collective sigh of relief in the room. We started shortly after eight o’clock, and in an hour and a half, we recorded nine songs. Nine. When he finished, Frank was jubilant. We were in the control room listening to the playback, and I looked over at him and said very quietly, “Too bad Mo can’t hear this.”

Frank grinned. He turned to producer Phil Ramone and said, “Crank that shit up. I want them to hear it over the hill at Reprise.”

There were several more nights of recording while Frank laid down the remaining vocals. But some of the tunes, like “One for My Baby,” were one take. The sessions were giving me goose bumps. I stood there one night thinking, This is the same studio, the same exact studio where 35, almost 40 years ago, the same musicians were in this same place, recording this same tune for the first time.

With Frank’s vocals down, the other performers could go to work. Some of the performers were not even in this country when they laid down their tracks. There were people sitting at Capitol in Hollywood and people on other continents. Bono was in Ireland. Charles Aznavour was in Paris. It was the first time an album had ever been done that way. The process was done with a technology called Avnet. Basically, they were playing the original recording in Hollywood over a secured line, and the other singers were listening to it and laying down their tracks in an isolation booth at a remote location. Then it was put together in post-production.

Overall, it went very well, but we did have one little hiccup. We got a call from Phil Ramone one night, saying that Barbra Streisand had finished the recording, and it had come out phenomenal. However, she’d decided to personalize the tune, and she’d sung, “Oh, you make me blush, Francis,” without telling anybody she was going to do it. So now the producers felt the need to have Frank personalize it back. At first, Frank didn’t want to have anything to do with it. We were in Connecticut at Foxwoods casino, not in a recording studio. He didn’t really want to personalize a song for someone besides his wife, anyway.

I pulled him aside and said, “Frank, what’s your wife’s name?”

“Barbara.”

“Well, don’t sing to Streisand. Sing to your wife.”

He thought a second and shrugged. “That would work.” We brought a Nagra recorder into Frank’s inner dressing room, and Frank told the crew, “Keep it down. We’re doing something really special.” Frank recorded that one line, “I have got a crush, my Barbara, on you,” on the road, in a dressing room, in a casino in Connecticut. That’s show business.

That year Capitol Records created an award called the Tower of Achievement Award, after the Capitol tower in Los Angeles. It was the first award of its kind, and they gave it to Frank as part of the Duets celebration. Frank was ecstatic. One of my favorite memories is when Frank found out Duets had knocked Pearl Jam out of first place in the music charts. Frank was absolutely thrilled that he could do something like that at his age.

“Eighty years old, and I just knocked out Pearl Jam!”

Excerpted from Sinatra and Me: In the Wee Small Hours by Tony Oppedisano. Excerpted with the permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Copyright © 2021 by Tony Oppedisano.

You Might Also Like