Inside the deadly government guns program that made the US less safe

It was Jan. 18, 2011, in Phoenix, Ariz., and Peter Forcelli, a special agent for the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), picked up a 911 call about a robbery in progress.

When he arrived at the scene, it was obvious something horrible had happened.

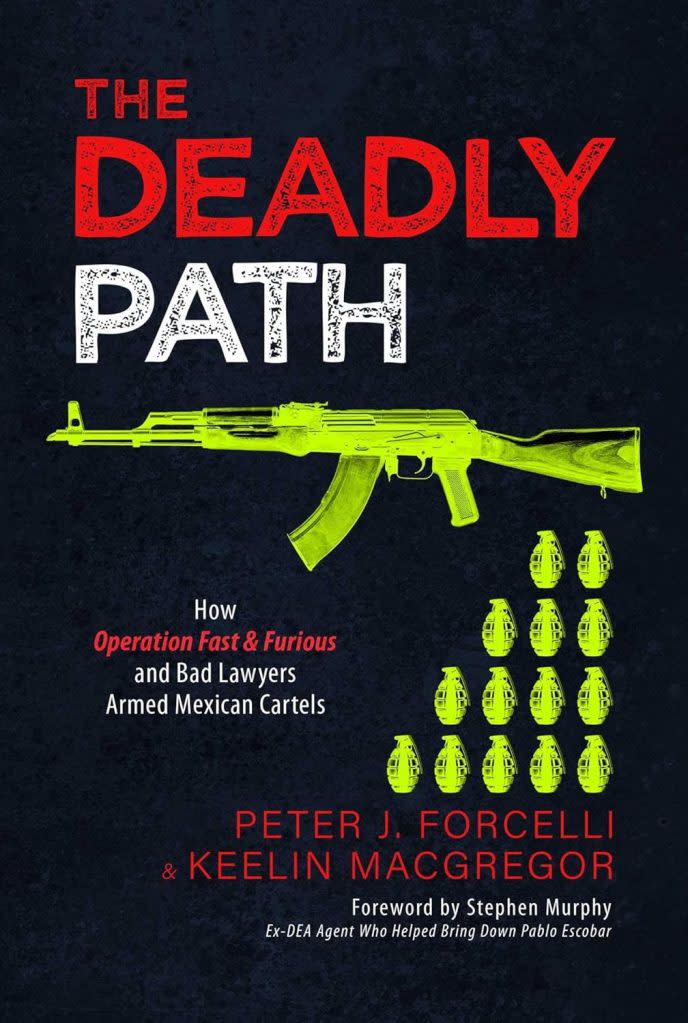

“As we stepped through the doorway, the tang of metal hit my nostrils,” he writes (with co-author Keelin MacGregor) in his new true-crime memoir, “The Deadly Path: How Operation Fast & Furious and Bad Lawyers Armed Mexican Cartels” (Knox Press), out now. “A slippery sheen coated the floor. Blood. Lots of it.”

The former NYPD homicide detective was no stranger to crime scenes.

Given the vast amount of fresh blood, whoever was involved was either dead or gravely wounded.

But the house was empty, and the only evidence that remained were the guns.

Forcelli and his team, who specialized in federal crimes involving gun trafficking, were recording the weapons’ serial numbers when they got a call from their superiors at the Department of Justice. They were instructed not to continue their investigation, even if it could lead to identifying the murderer.

“I could hardly believe my ears,” Forcelli writes. “We were standing in a bloodbath where the gun was found, and my team (was ordered) to stand down?”

Forcelli, who was sworn in as an ATF agent in 2001, was transferred to Phoenix in 2007 to focus on stopping the illegal flow of American weapons into the hands of Mexican drug cartels. But as he soon discovered, his team was often “forced to allow people blatantly involved in firearms trafficking to go free,” Forcelli writes. “It flew in the face of everything I had experienced in the previous 22 years in law enforcement.”

Much of the problem was thanks to Operation Fast and Furious, a program initiated by ATF’s Phoenix Field Division in 2009, which allowed suspects to walk away with illegally purchased guns—otherwise known as “gunwalking” — in the hopes that they’d lead agents to key figures in Mexican drug cartels.

The problem, however, is that once those guns crossed the border, they were no longer the ATF’s problem. Or as it was explained to Forcelli by a prosecutor, “The body of the crime is the gun, not the person. If the gun is in Mexico, the body of the crime is in Mexico.”

Not only did ATF agents watch as known smugglers drove off into the sunset. There was also the fear that those guns would come back to haunt them. In December of 2010, that very thing happened, when customs border agent Brian Terry, patrolling the desert just outside of Nogales, Ariz., was shot and killed with a gun that was later traced to a Fast and Furious investigation.

Fast and Furious wasn’t the only fly-in-the-ointment keeping Forcelli from doing his job. Corpus delicti, the legal policy that a person can’t be convicted of a crime without concrete evidence that it actually occurred, ended several of Forcelli’s investigations that should’ve been slam-dunks.

Once, after pulling over a truck headed to the Mexican border, Forcelli and his team discovered several AK-47 rifles and a dozen cases of 7.62 mm ammunition.

Everyone in the truck had Mexican identification cards. But the attorney’s office in Phoenix declined to prosecute. Forcelli was told that arresting any of the obvious drug smugglers “could be perceived as racial profiling.”

Then there was Forcelli’s multi-month investigation of X Caliber, a gun shop in the northern suburbs of Phoenix. An undercover ATF agent, posing as a “straw buyer” — the middlemen hired by Mexican cartels to purchase firearms on their behalf — attempted to purchase weapons from the shop’s owner, George Iknadosian, who unknowingly revealed details about the ins and outs of gun smuggling.

“Fridays are bad days to move guns to the border,” Iknadosian confided in the undercover agent, his admission captured on a wiretap. “Mondays are much better. Police are busy following up on what they did over the weekend.”

Iknadosian was arrested and indicted on 21 charges, including conspiracy to traffic weapons, money laundering, and fraud schemes.

Almost a year later, drug lord Arturo Beltran-Leyva was killed in a shootout with Mexican Marines. Nearly a dozen firearms were discovered near his bullet-riddled body, all of which were trafficked from X-Caliber, “including an ornately bejeweled Colt .38 Super semi-automatic pistol,” Forcelli writes. “Fitting . . . for a man known in the narco-trafficking world in Mexico as The Boss of Bosses.”

In June of 2011, Forcelli testified before Congress and blasted the ATF and federal prosecutors for their failed gun smuggling policies and enforcement operations, which resulted in over 2,000 guns disappearing across the Southwest border.

“What we have here is actually a colossal failure in leadership from within ATF,” Forcelli told Congress. “We weren’t giving guns to people who were hunting bear. We were giving guns to people who were killing other humans.”

Forcelli, who retired from the ATF several years ago, isn’t convinced that much has changed since his whistleblowing.

“The same policies and people remain in significant positions of power,” he writes, “with no intervening oversight.”