Inside Buckingham Palace’s Resplendent, Never-Before-Seen Rooms

A New Book on Buckingham Palace Captures Resplendent, Never-Before-Seen Rooms

As I discovered when I curated the Commonwealth Fashion Exchange, Buckingham Palace is a place of marvels, with utilitarian service spaces that open surreally onto enfilades of suitably majestic rooms designed to both entertain and dazzle.

Ashley Hicks was given the dream assignment: To set himself loose in the storied palace for ten days with a Canon digital SLR with a mission to capture some 21 of its splendid rooms, several of them never open to the public. (There was, admittedly, a certain level of trust: Hicks’s grandfather, Lord Mountbatten of Burma, was Prince Philip’s uncle, and Prince Charles is Hicks’s sister India’s godfather.)

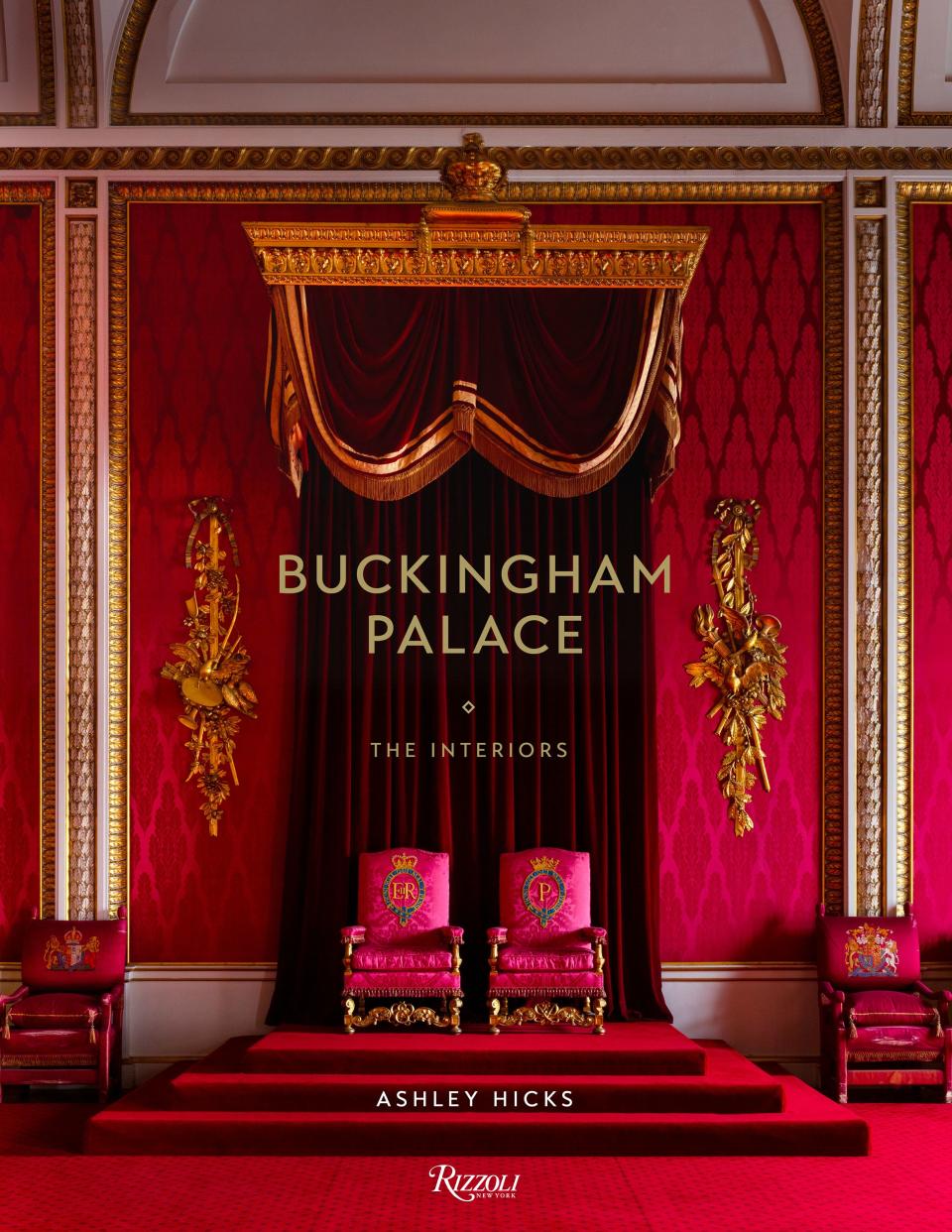

Hicks decided to photograph them all in the natural light that streams in from the vast windows, and the results, showcased in Buckingham Palace: The Interiors, are sensational: The gilding dazzles, bronzes and hardstones gleam, crystal coruscates, and the saturated colors simply throb on the page. And what colors! The faux lapis scagliola of the columns in the Music Room (which one Joseph Browne was paid one thousand, two hundred and fifteen pounds to garnish in 1815) have recently been restored to their original splendor; the crimson of Thomas Nash’s Throne Room, with its Carolean revival thrones made for Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip by White Allom & Company in 1953; and the yellow curtains and upholstery in the White Room, dominated by Francois Flameng’s portrait of Queen Alexandra—whose beauty was by then much enhanced with new-fangled cosmetics—wreathed in pale satin and tulle.

There are Winterhalter portraits everywhere you look, along with pale marble caryatids and elaborately inlaid floors and crystal chandeliers and the Order of the Garter woven into a thick carpet, but Hicks has recorded unexpected anecdotal details, too: An 18th century desk swiped from the French royal collection after the Revolution has its fragile marquetry protected from the sun by a linen shroud; an unsuspected jib door that leads into the Royal Closet, where the royal family gather before state occasions. That room itself is fitted with luxury-loving George IV’s architectural treasures, this time hauled over from his bachelor residence, Carlton House, and cabinets filled with acquisitive Queen Mary’s collections of porcelain etuis and hardstone Chinese objects. Hicks’s remarkable eye also captures the sort of details that could not be clearly seen from behind velvet ropes, such as Phaeton’s chariot in gilt bronze cresting an Empire mystery clock, or a Roman bacchanale in a carved marble mantelpiece.

Since 1993, the palace has been open to the public every summer when Queen Elizabeth decamps to Balmoral, her castle in the Scottish Highlands, for her holidays. Visiting is one of my favorite things to do in London (and the adjacent Queen’s Gallery generally has an inspiring exhibition). Of course, the greatest revelations in Hicks’s book are his images of the rooms that are not on the public tours, notably those in Queen Victoria’s Blore wing, which was built to link the former U-shaped building (creating an enclosed central courtyard) and provide a new facade. These rooms open onto the famous balcony where the royal family gathers for such events as the Trooping of the Color, or a royal wedding kiss. It is amusing to discover that they are filled with the eccentric Chinoiserie furnishings, fireplaces, and architectural elements that Queen Victoria thankfully had installed (reluctantly, by Blore) from her uncle George IV’s other great extravaganza, Brighton Pavilion. As regent and as king, George IV was reviled for his free-spending ways—the government, ergo the British people, were constantly having to bail him out—and his unrestrained taste was subsequently unpopular in Victorian England, so it is a tribute to his niece’s fondness for him that the pieces survive in all their dotty wonder. What Hicks’s images convey is the impasto layering of changing generational taste that makes this house, like so many other storied British homes, a place of such endless delight and discovery.

At the turn of the 17th century, the land on which Buckingham Palace now sits was a mulberry garden, planted to feed silkworms. When the Duke of Buckingham built a house there a century later, in 1703, it was essentially a very grand country establishment on the outskirts of town. Its design was apparently inspired by the work of William Talman, whose triumph was the Duke of Devonshire’s Chatsworth, and the artist Louis Laguerre painted the magnificent staircase (he was also responsible for Chatsworth’s imposing Painted Hall).

Soon after they married, King George III and Queen Charlotte bought the property from the Duke’s aged widow, and it became a royal residence at last. William Chambers and Robert Adam were summoned to make improvements, but the serious young king deemed Adam’s work too florid, and Chambers’ sober schemes prevailed. The king lived downstairs and didn’t seem inclined to change the existing old-fashioned scheme, whilst his wife’s apartments upstairs were soon redecorated in the height of fashionable taste.

When the king died after a long period of madness (we now know that he suffered from porphyria), his profligate son, George IV, who had been serving as a Regent for a decade, lobbied Parliament for yet more funds to transform Buckingham House into a palace fit for a king. He hired John Nash, who conceived an exuberantly theatrical scheme that was unfinished by the time he died. His brother, William IV, and Queen Adelaide, however, scrupulously followed the plans, but this king didn’t live to see them realized either. William IV’s niece, Queen Victoria, enlisted her aesthetically enlightened husband, Prince Albert, to supervise the works, but his brilliantly colored Renaissance inspired scheme was subsequently obliterated by his son, Edward VII, who seems to have whitewashed most surfaces. The architect Blore added a wing with more rooms to accommodate Queen Victoria’s indecently fast-growing family, and happily, as we now discover, she fitted some of them out with salvage from her uncle George IV’s fanciful Brighton Pavilion, done in the height of chinoiserie taste.

A generation later, the architect Sir Aston Webb reclad the already crumbling façade, transforming the exterior into the bombastic structure that we recognize today, and King George V’s formidable wife, Queen Mary, passionate about antiques and objets d’art, set to work on the interiors. In turn, her son George VI initiated more changes, and his wife Queen Elizabeth (later Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother), is rumored to be the force behind replacing the olive green damask in the great picture gallery in dusty-rose-flocked pink velvet wallpaper, which I always think gives the splendid gallery—hung with an untold treasury of superb Old Master pictures—the look of a 1930s powder room. Her daughter Queen Elizabeth II’s reign, meanwhile, had brought its own changes—and, in some instances (those faux lapis lazuli columns, for instance), scrupulous archeological restorations.

Are you following me? I know it’s a lot to take in, but so is this thrilling book, illuminated with Hicks’s photographs and informative and droll texts. Home will never quite seem the same again.