The Incredibly Happy Life of Larry David, TV's Favorite Grouch

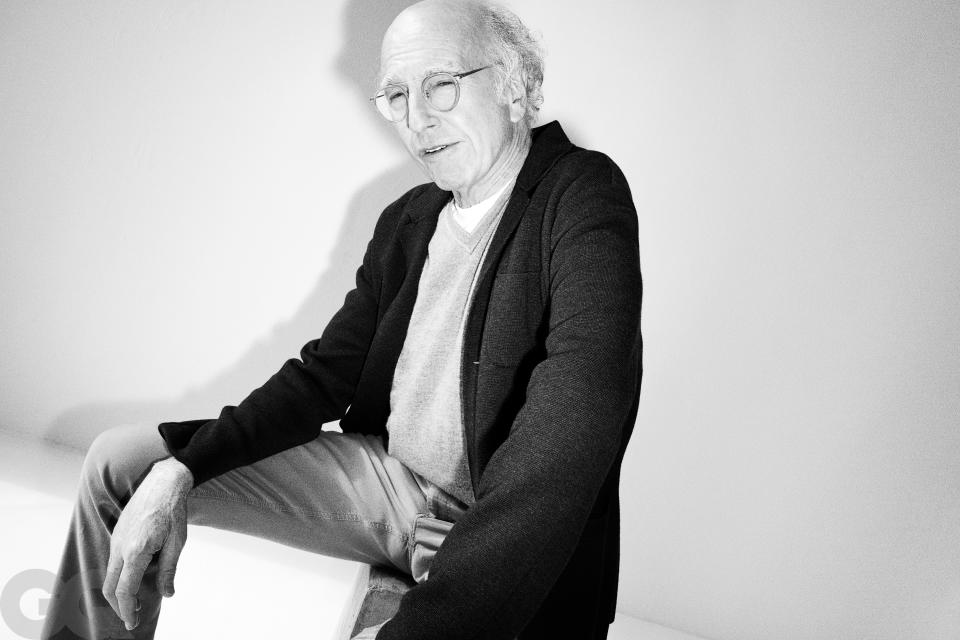

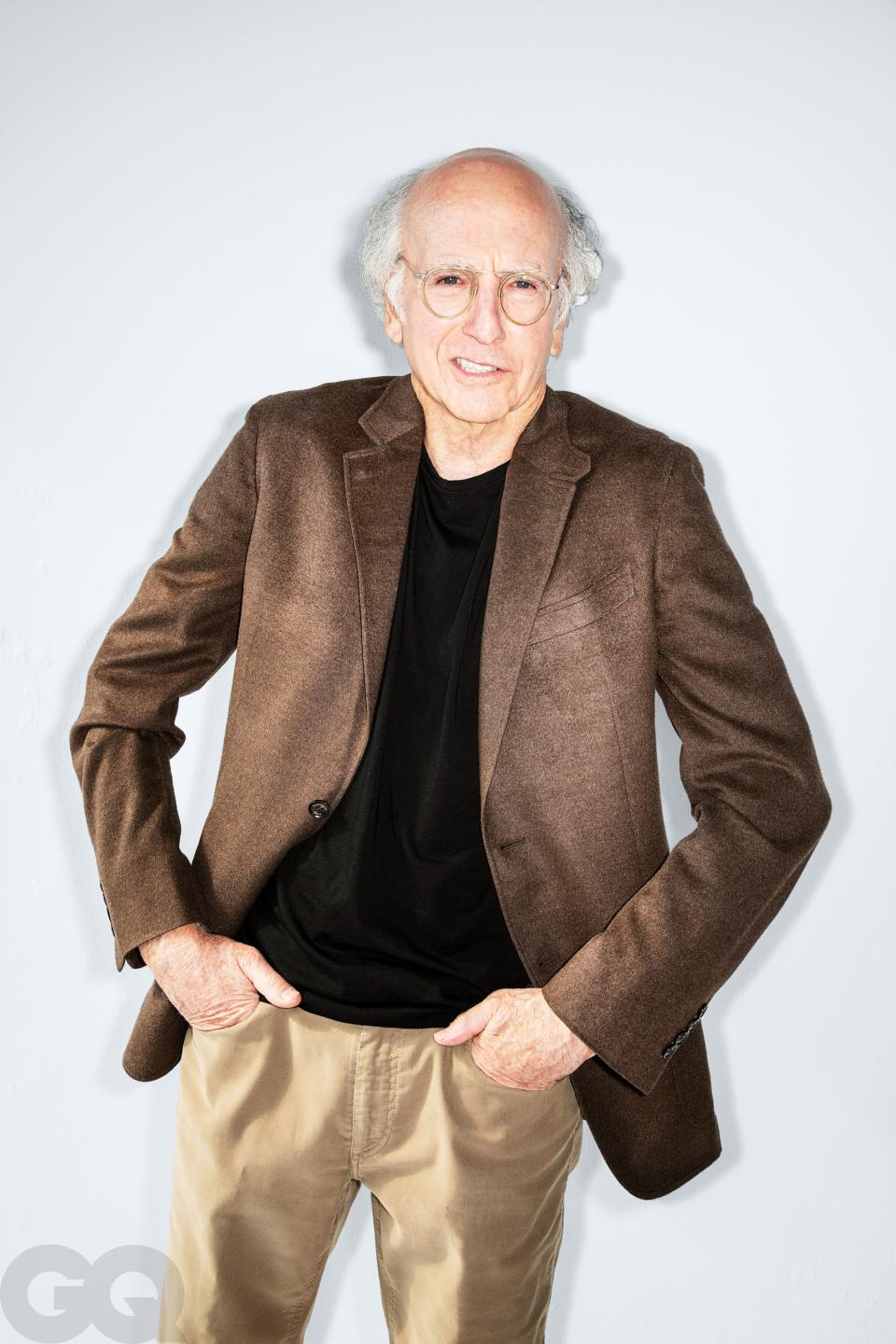

The kid is wearing a T-shirt reading “EAT MORE AVOCADO,” one of the designs for sale at this Venice Beach café at which he's a server, along with “WE SELL DESIGNER KALE” and “BEET IT.” He's waiting on me and Larry David, who is of course dressed precisely like Larry David—gray knit hoodie, dark long-sleeve T-shirt with a white shirt beneath that, beige jeans, and sneakers. David chooses or approves all the wardrobe for Curb Your Enthusiasm, and then he keeps all the clothes, from blazers to socks, creating a seamless visual loop between Larry and the character he calls TV Larry.

So Larry David is sitting there, using his very Larry David voice to discuss very Larry David things: breakfast preferences (today, scrambled egg whites, grilled onions, and sliced avocado), the relative pleasures of killing flies and ants (flies are more satisfying), and yes, clothes, about which, unsurprisingly, David has Thoughts. The son of a garment-district salesman, David has always approached clothing with something of a tailor's eye. The very first Seinfeld gag was about shirt-button placement; the first Curb Your Enthusiasm centered on a crotch cut too big, thus simulating an erection. He has a code: One should wear only one “nice” piece of clothing at a time. “Otherwise it's too much,” he says. “Too dressed. You have to be half-dressed. That's my fashion theory, since you asked: Half Is More.”

In nearly two decades of interviewing people for this fashion magazine, I have rarely spent even this much time discussing fashion. But then I've seldom profiled a Fashion Icon. Is there a more recognizable, self-assured, incredibly specific wardrobe to be found anywhere in pop culture? The tear-shaped Oliver Peoples glasses alone have now approached a Groucho Marx or John Lennon level of personal identification. David has worn them since the early 1990s. He used to own only two pairs, until a suitably paranoid producer recently went on a worldwide hunt and came up with a few backups. They were the first thing he grabbed last October, when the Getty Fire forced him to evacuate his Pacific Palisades home.

“Jerry said I dressed like an Upper West Side communist,” David says, referring to the Jerry with whom he created Seinfeld, back in 1989. I think of the look as Alpha TV Writer: In a profession where status is measured by how casually and comfortably one can arrive at work, David's wardrobe qualifies as a kind of normcore bling.

In the course of all this pleasant kibitzing, David's decaf Americano has gone tragically tepid. He beckons to the Avocado Kid, who has hovered nearby.

“Let me ask you,” David says. “To make this a little hotter, you have to make a whole new thing, right?”

“Or dilute it,” says the server. “But we'll probably just make a whole new thing.”

“I'm going to tell you in advance, I'm only going to drink about this much of it,” says David, fingers measuring a tiny pinch.

“It is what it is,” the kid says agreeably.

“You know what? Put it in the microwave.”

“We don't have a microwave.”

“Okay,” says David. “Let's forget it.” The kid shrugs, apologizes, and withdraws as David and I return to our discussion, which has now moved on to his disdain for the supposed innovation of UNTUCKit shirts: “Like nobody ever wore their shirt out and noticed that it was too long? We all noticed.…”

But lo! Just as he gets rolling, the server returns, having seized the initiative and bearing a fresh hot carafe of Americano. “I just had him make another one,” he says proudly as he tops off our cups. “Great, thank you,” says David. And then he pauses a long moment.

“But…just for the sake of discussion…” He purses his lips, raises his eyebrows. “Shouldn't you have brought a new cup?”

“What?” says the server.

“So you don't put it in the old, cold coffee. Here, let me see.” He takes a delicate sip.

“Is it hotter?” asks the server uncertainly.

“It's a little hotter,” concedes David. “But don't you see how you defeated the purpose?”

The kid has a small grin frozen on his face. On the one hand, there is a real customer-service situation to be reckoned with. On the other, he must feel, as I do, deeply disoriented, as though he has passed through the looking glass and into an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm. It's like getting a living room concert from the Rolling Stones.

A few more seconds and the server snaps out of it, finding his line. “Well…live and learn,” he says, smiling. “Every day I'm working on my craft.”

David grins too, gratified by the repartee. “I know, I know,” he calls after the server as he moves away. “I know you're going to be a great waiter someday!”

I have, in the line of duty, met actors who seem like they are continuing to play their most famous roles in real life—Pierce Brosnan, say, who ordered a martini in the opulent hotel where we met without so much as a knowing Bondian wink. Never before David, though, have I been around a celebrity whose actual persona so immaculately and surreally matched their onscreen one.

The simplest explanation is that they are the same person. Or close enough that it would be hard to fit the page of a script between them. David bestows his own travails and kvetches on TV Larry, of course. But also his existence is so circumscribed—“My whole life is spent in three places: home, the office, and the golf club,” he says—that some things that happen to TV Larry because they happened to Real Larry wind up happening to Real Larry again. When we leave the restaurant to retrieve David's Tesla Model S from a lot, he initially attempts to give the valet ticket to a dark-skinned guy in a reflective vest who just happens to be standing near the entrance—a mistake exactly like one made by TV Larry way back in season four.

For all these circles within circles, the Case of the Diluted Americano is cut-and-dried: “Am I supposed to not say something?” he says.

“Yes, you're supposed to not say something,” I say, feeling like a Pollyanna.

“So most people would not say something.”

“Of course not.”

“Even if he didn't know me, I would have said something,” he insists. “After all, what did I do? I pointed something out. I didn't insult him or anything.”

It is almost reflexive—for reasons of temperament and ethnicity—to describe David as “neurotic.” Sitting there with him in what I had already begun to think of as Larry World, I start to believe maybe this is exactly wrong. It occurs to me that Larry David may be the most self-actualized person I have ever met.

In truth, my time in Larry World begins several weeks before we meet in Venice. For one thing, we've talked on the phone, during which call David has assured me that this whole thing—story, photo shoot, magazine cover—is going to be a disaster. “I'm trying to figure out who to pay to get out of it!” he said. This is something he's done before, with other writers about to attempt profiles, but there's no reason to believe it's not heartfelt. He's talked to my editor, too, warning that if the plan is to get under his surface, I might as well give up now: “Believe me, there's nothing there!”

Also, for several weeks, I've been immersed in watching or rewatching the 90 episodes of Curb Your Enthusiasm that precede the 10th season, about to begin on HBO. It is not uncommon, in the midst of such binges, for the fictional universe of the binged show to bleed into the tenor of real life, but this is an especially hard case. My world suddenly seems filled with egregious slights and social transgressions, a vast parking lot of carelessly parked cars. An editor emails to offer me an assignment. I write back with the sign-off “Nice to meet you,” though I realize, as I click Send, we met years before. “No worries,” he writes back, after pointing this out, but it's the last I hear of that assignment. I can't help but notice a friend's habit of letting me pay for the Uber when we go out to dinner but then arranging for another friend to drive us home for free. I decide, after a year of thinking about it, to ask the woman who cuts my hair about the protocol of tipping her, since she also owns the salon. It goes really terribly. Larry World, I start to see, consists less of a series of imaginative events than a perpetual state of combat, righteous or otherwise, with the universe. It is exhausting.

To some extent we all live in Larry World; it's why Curb's theme song, “Frolic,” works laid over nearly any video on YouTube. I should admit, though, that I may be especially susceptible. David and I grew up in adjacent Brooklyn neighborhoods and attended rival high schools, albeit 25 years apart. He is such a kaleidoscopic amalgam of men I grew up surrounded by—grandfathers, uncles, great-uncles, teachers, Jackie Mason, Alan King, Woody Allen, Mel Brooks, men in black socks trudging across the sands of Coney Island selling knishes: all the alter kockers of my Brooklyn Jewish youth—that I can't always be sure I haven't known him my entire life. So deep is the ancestral chord he strikes in me that whenever I hear the opening tuba of “Frolic,” I practically taste whitefish.

It's something of a mystery to me that the sensibility seems to resonate as vividly everywhere else in America. Twenty-two years after it went off the air, Seinfeld remains omnipresent, a staple of local TV in places across the country where people don't know their Boca from a babka. Netflix recently secured the streaming rights to the series for a reported excess of $500 million.

“I want someone to explain it to me,” David says, when I ask about the enduring appeal. “I really don't get it, other than—and it's not very profound—it's funny. And when something's funny, people like it.”

Meanwhile, Curb has been with us since shortly after the last presidential impeachment. It was the comedy component of HBO's invention of prestige TV, arriving hot on the heels of The Sopranos, whose creator, David Chase, once told me, in what I took as at least 75 percent seriousness, that he thought he and David could have switched places, with Chase writing the comedy and David the drama. Now Tony Soprano is long gone, along with Don Draper, Walter White, Vic Mackey, and the rest of his cohort. Only Larry persists: The Last Difficult Man.

Unrepentant white-male bad behavior may be slightly less fashionable these days, but Larry's crimes and misdemeanors are so well established that they feel grandfathered in. (This may be tested by a #MeToo plotline in season 10, about which I am permitted to say no more, given the modern fetish for TV secrecy. “Larry wants every show to be like a pimple,” says executive producer Jeff Schaffer. “You have no idea it's coming; just wake up in the morning and it's there.”) For the most part, Curb has sailed into the third decade of the 21st century unmolested by events and changes outside—or, really, even inside—its bubble. Wars may rage, despots may rise, divorces may be endured, both onscreen and off, TV Larry will still find time to obsess over the intricacies of party invites and thank-you calls.

“Come up with one example where I've done something bad. I don't think you'll find it.”

“Everybody's worried about the big things, like climate change and corruption,” Schaffer says. “Somebody's got to focus on the little things.”

Curb Your Enthusiasm, at the beginning, had the distinctly casual feel of a victory lap, its title poking fun at the notion of expectations. “In the early days, we'd get the call from Larry himself: ‘Can you come down tomorrow?’ ” says Ted Danson, who began appearing in season one. “You know, bring whatever clothes you want. There were no trailers. You kind of sat in your car until they were ready for you. It was really sort of guerrilla TV making.” (David can lay at least partial claim to the Dansonaissance that transformed the fading beefcake of late Becker into the white-haired sexy praying mantis we get to enjoy today.)

Ten seasons in, the production may be more professionalized, and the budgets bigger, but the show is made more or less as it always has been: David and Schaffer—a former Seinfeld staffer and creator of the Curb-influenced The League who has been on board since season five—labor over outlines for each episode. The scenes themselves are improvised. Though Curb has been a Grand Central Terminal for famous cameos, the process is not for everybody. Some actors come in trying too hard to be funny. Others have trouble negotiating the tricky landscape of exactly how to insult Larry. On the one hand, he loves abuse and is notorious for bursting into laughter whenever somebody lays into him. (“Do me a favor, just quote me in the article as saying, ‘I adore Larry David,’ ” Danson told me, dissolving into giggles. “He'll hate that!”) On the other hand, it is not exactly open season.

“There's a few things you should never do in an audition with Larry,” says Schaffer. “One is that unless the scene absolutely calls for it, don't start to cry, because then the scene is just over. Two, try not to touch his face. Just don't. And three: There's a difference between insults for comedy and just being plain insulting. Larry is sensitive.”

“I've been called terrible names,” David says. “ ‘Old’ used to really bother me, cut me to the quick.” He says he only expects that others abide by the same code he follows himself: “I never cross a line where I'm commenting on somebody's looks. Never would I say anything that could personally hurt or insult somebody.”

I have always understood Curb Your Enthusiasm to be about the existential horrors of being rich. The show makes the most sense to me as the continuation, on some transdimensional plane, of the last moments of the Seinfeld finale, in which the four characters are revealed to be in an ever repeating hell of their own petty narcissistic making. The Larry of Curb, as I imagine him, is George Costanza set horribly free, untethered now to civil society by even the flimsy bounds of the need for employment: The Stranger in Brentwood.

This, David wastes no time in letting me know, is all nonsense. To his mind, TV Larry is no antihero. He is a real hero.

“When I was told that there were moments in the show that made people cringe, I was shocked. It never occurred to me,” he says.

“What do you think is the animating emotion of the show, then?” I ask.

“I just thought people were going to enjoy it. I'll tell you this: If something made me cringe, I don't think I'd put it in the show.”

“So Larry is just a truth teller?”

“Yes.”

“He doesn't cross the line at all?”

“He's expressing himself.”

“And it's admirable.”

“Totally. When you think of the way we conduct ourselves in life, how much bullshit we have to endure, how much bullshit we have to listen to and how much bullshit comes out of us just to avoid hurting someone's feelings. All these rules we set up for ourselves.… I don't think I'm a bad guy. I'm honest. I'm not mean. I'm never cruel. Come up with one example where I've done something bad. I don't think you'll find it.”

I mention a scene, from season seven, in which TV Larry stops a little girl, Jeff and Susie's daughter, from singing at a party. He smiles.

“To me that's too funny to be mean. When it's funny, it's not mean. It's just funny.”

Are there things TV Larry does that he wouldn't do?

“I wouldn't do anything,” he says. “Would I ever stop a girl from singing in my life? No. Would I stand there thinking, ‘Boy, I wish I could stop her?’ Yes! That's why there's a show.”

Of course, as the Case of the Diluted Americano made clear, the line is hardly absolute—and less so all the time. TV Larry may have begun as an avatar for all the things Real Larry wished he could say but couldn't, but the longer the former exists, the more the latter can get away with. This pays dividends for those around him too.

“We get a social pass,” says Ashley Underwood, his girlfriend of two years. “We'll be at a dinner party, and Larry will take his last bit of food and just stand up for us to go. I just shrug. He gets the laugh, and I get to ride his coattails.”

David knows you did not like the Seinfeld finale. When Curb ends, he's resolved, it will do so without ceremony.

“I guess you might as well come to my house,” David says, with what can be described as enthusiasm well curbed. So I find myself winding my way up the hills of Pacific Palisades, streets lined with the hodgepodge architecture of Westside wealth—Tudors, Colonials, Mission Revivals—sidewalks empty except for gardeners and the occasional power walker with tiny dogs in tow. This, too, is indisputably Larry World: It is as easy to imagine David on Mars as it is in Silver Lake.

Looking clear through the entryway when David throws open the door, out the large picture windows at the back of the house, I get the illusion that we are suspended over a void. David walks us to the patio, which reveals itself to be perched on the wall of a canyon overlooking the dewy green paradise of Riviera Country Club. Soft-glowing viridescent fairways roll out toward distant hills, shrouded in mist and pocked with moon-white bunkers. A single golf cart crawls silently across the landscape as a flock of emerald parrots swoops by. It's like White Wakanda.

“How long before you started to take this view for granted?” David asks. “For me, it's two days. I'm a two-day take-for-granted guy.”

That's why you have people over, I suggest. To experience it through them. David considers this trade-off. “Nah,” he concludes.

He is, nevertheless, a very affable host—engaging, curious, and as many have noted, an easy laugh. David, at 72, is one of those screen people who actually look healthier and heartier in real life—more country-club dad than knish man. There is still, of course, his Diary of a Wimpy Kid body, like two pipe cleaners twisted together; the long hands, gesticulating like startled doves; the gleaming teeth. He walks with a kind of jaunty, dead-armed lope that sometimes threatens to tip to one side, as though he were on the deck of a listing ship. For someone whose comedy is so verbal, he would have made a tremendous silent-film star.

We go on a tour of the house. “For it is Mary, Maaary,” he sings grandly, an old George M. Cohan tune, as he leads the way upstairs with what seems perilously near to a bound in his step. At the top of the carpeted stairs is, actually, Mary, his housekeeper.

“Mary, tell him what a tremendous boss I am,” he says. “El mejor, right?”

“Oh, yeah. Right,” says Mary.

We pass through bedrooms and sitting areas, back downstairs to a home gym outfitted with workout machines and a massage table. On the walls are framed photos of David with his two daughters as babies, others of him with the Obamas. There's a large print of David's family tree, produced for Henry Louis Gates Jr.'s ancestry show, Finding Your Roots, on which he discovered that he and Bernie Sanders are distant cousins. He takes another photo off the wall, a class picture from the first grade at P.S. 253, 1953. It takes only a moment to spot David in the back row, with a toothy grin and elfin ears, and only a moment more to guess which of the paintings hanging over the blackboard, amidst happy animals and flowers, is Young Larry's: It's the one of the boat covered in swastikas.

“I wasn't brought up to think that I was going to be able to do anything,” David says. “It never occurred to me that I could go on and make something of myself.”

David has lived in this house for 10 years, since soon after his divorce. His daughters, now 25 and 23, spent their adolescence here. (The presence of kids is one of the major ways David's life diverges from that of TV Larry, who is childless.) Underwood moved in last year, bringing a fluffy black-and-white cat named Elwood, who now curls up next to David on the living room couch and accepts a good scratch. The couple recently adopted an Australian shepherd puppy whom, after much discussion, David says, eyes twinkling for the reveal, they named Bernie.

All in all, it is a place that in every way radiates great success. None of which, it seems, has accrued to any sense of inevitability—a conviction that had Jerry Seinfeld not caught up with him backstage at the comedy club Catch a Rising Star one night in 1988 and asked him to work on a show for NBC, some other path would have emerged. “Let's face it, if Seinfeld doesn't come along, what happens to me, really?” he says. “Here's what I think: I think I'm living in a studio apartment in New York. I think I'm miserable doing it. I think I hate everything and everybody, including myself most of all. I think I'm a guy walking down the street, screaming at people for slights like a bump-into without a sorry, things like that.”

I say that I find it a little terrifying, the idea that one's direction in life could be so tenuous.

“I do too,” he says. Nevertheless, he's committed to this worldview. “This whole ‘happiness from the inside’ thing…where's it coming from? What am I feeling good about? You have to have some sense of accomplishment.” There was a dark period, as a failing stand-up in New York, when his parents paid for him to seek therapy. “I couldn't have hated it more,” he says. “Because I knew that you need two things. You need money and you need a girlfriend. With no money, there's no girlfriend. Of course, I hated myself deeply, but that's because I didn't have the money and the girlfriend. If I had the money and the girlfriend, I knew I would hate myself a little less.”

David has consistently said that he had no sense of being funny until leaving home for college, at the University of Maryland, where all his Brooklyn mannerisms were suddenly exotic among his gentile classmates. His childhood, in general, seems to have been something of a cipher. He is at a loss to describe what pre-funny Larry David was like. “I don't remember. I mean, I was kind of quiet,” he says. “I wish I could get hypnotized and go back to my 15-year-old body and experience that again. And then go to 10, and then six. That would be interesting.”

Young Larry watched Phil Silvers and Abbott and Costello, read Mad magazine, summered in the Catskills—all the comedy-nerd touchstones of his generation—but without a premonition of a future calling. “I wasn't brought up to think that I was going to be able to do anything. I don't know whose fault that was, if it was my parents' fault or it was just something in me, but it never occurred to me that I could go on and make something of myself,” he says. “Nobody ever said to me, ‘You can do something.’ ”

It was performing stand-up comedy that gave David his first sense of purpose, even if his strange and somewhat antagonistic act didn't exactly vault him to stardom. Stand-up looms as a benchmark of success in David's mind, and something of a white whale. The one-hour special from which Curb sprang was ostensibly about his return to the art form, which, of course, the program's own success derailed. “I suppose it's always been somewhat unresolved in my head. That I didn't do it the ‘right way,’ ” he says. “I used to think, when I was younger, that this was what I was meant to do. That this was my calling, stand-up. I guess it still kind of bothers me that I haven't conquered the form the way I thought I would.”

He could, of course, wake up tomorrow and have a special on the network or streaming service of his choice—with a significant sack of money, to boot—but that only adds to the pressure, and to his ambivalence.

“I have such mixed feelings about it. The one aspect of it I don't like is that they”—the audience—“are in control of how I feel. I have to do something to elicit a response, and if I don't, I'm going to be in trouble. I have to please them, and there's something about that I don't like,” he says. “On the other hand, when I do please them, it gives me a great deal of pleasure.”

Other setbacks bother him less. He knows you did not like the Seinfeld finale. It bugged him for a while, but now he just makes a preemptive joke when the subject arises. When Curb ends, he's resolved, it will do so without ceremony. “I would never do that again,” he says. His feature-length efforts—Sour Grapes, in 1998, and Clear History, released in 2013, during Curb's six-year layoff after season eight—have failed to capture the spark he's brought to the half-hour form. “I don't know; some people are better at short stories than novels,” he says with a shrug. As for David Chase's fantasy of switching places, David says he has never had the urge to write a drama. “If it's funny, I know it's good. Otherwise I'm completely lost,” he says.

Our plan has been to visit Riviera—the last of the places David spends his life—but there's a hiccup. With Larry World up in my head, mindful of a plotline involving F. Murray Abraham as an “outfit tracker,” from the show's most recent season, I have been extra careful not to wear the same pants today as yesterday. As a result, I've got on jeans, which are verboten at the club.

“This is all because of your stupid show!” I complain.

“I was not outfit tracking you!” David says.

I say, “Are dress codes not among the social conventions we eschew?”

“Of course.”

“ ‘Bullshit,’ right?”

“Ridiculous!”

“Then why do you follow them?”

David shrugs. “It's golf. Allowances must be made.”

Squeezed, then, into the largest pair of pants Larry David can find in his closet, I sit beside him on the two-minute ride down the hill to Riviera. He keeps his window up as we pass the booth at the club entrance, where a chatty attendant once inspired a Curb plot. TV Larry confronted that annoyance, with predictable results; Real Larry wrote something about it down on his phone, duly transcribed it into one of the large spiral notebooks of ideas he always has working, and lived out his revenge onscreen. Still, when that attendant left, the new one didn't get window privileges.

David parks the Tesla in the space closest to the clubhouse, and we stroll out through the men's locker room and to the first tee. It's an unusually quiet day in the club, and we jump in a cart to take a short spin around. “This is really the only thing I like to do outside,” David says.

“What about swimming?” I ask.

“Hate the water.”

“Bike riding?”

“Never.”

“Hiking?” He makes a noise as though I've suggested a nice case of leprosy.

“The beach?”

“Could not hate the beach more.”

We pass the driving range, where a lone figure, short and wiry, pauses between swings. “That's Johnny Mathis,” says David. He calls, “Hey, John!” Johnny Mathis waves.

“Can you begin to see the appeal?” David says, gesturing at the landscape as we circle back toward the clubhouse. From a nearby green, a fellow member calls out “LD! Living legend!” David raises his hand in a pope-like manner. I begin to see the appeal.

We swing into the clubhouse dining room. David seats himself at the one spot of a four-top not made up with silverware, near a huge TV showing coverage of the Trump impeachment hearings, and orders a salad—debating and then allowing himself the luxury of adding turkey. “Oh, yeah, yeah,” he shouts sarcastically at the screen when the president appears to make a statement. “Stop lying, you asshole!” He is aware that in the wealthy precincts of the club there are sometimes other members nearby who feel differently about the administration. “I talk louder on purpose when they're around,” he says. “To me, if somebody bought Fox News, I would feel the same as I felt when the Berlin Wall came down. That feeling of euphoria, like the world was going to change.”

We head back up the hill to his house. For two days, I've continued to mull the “neurotic” question: Is he or isn't he? To be sure, he is a creature of routine, verging on the compulsive; he must make the trip into his office every day, even if only for a brief visit. He dislikes travel, with all its disruptions. He is an assiduously healthy eater and claims to be something of a hypochondriac, but then admits he doesn't “rush off to the doctor” at every provocation, which I'm pretty sure gets you kicked out of the hypochondriac club. And some of his social hang-ups clearly are not shtick. “I've lost all ability to talk to people at a social gathering,” he says at one point, shaking his head. “I don't know what it is. I just can't even face them. It gets worse all the time. I can't go to parties anymore.”

Still, I'm forced to conclude that Larry David, for all his demands on the world, suffers very little from its perpetual failures.

“People are under the wrong impression when it comes to me being happy or not,” he says. “I think most people think that I'm miserable. Or that I'm a very disgruntled person. But I'm not. I have a very good disposition.”

When it's time for me to leave, David walks me toward the door but then stops. I see the pursed lips and raised eyebrows and brace myself. “Let me ask you a question: At the club, which urinal did you use?”

“Say again?”

“When you went to the bathroom at Riviera. Which urinal?” He pantomimes the layout of the club's men's room. “You walk in, and then there are three urinals—closest, middle, and farthest from the door. Which do you think is the right one to use?”

“Which one do you think?” I ask warily.

The first or second, he explains, on the reverse-psychological theory that most people will choose the third, thinking it the least used, thus leaving the others cleaner.

“Aha!” I pounce. “But you can't use the middle one, because that then forces anybody who comes in to stand next to you, whichever one they choose.”

I am sure now that I could stay here forever, discussing these pressing matters while the California sun rose and set a thousand and one times on Larry World. But we've already reached the door.

“Okay, okay.” David nods as he opens it. “I hadn't really considered the Neighboring Factor. Okay.” And then he sets me free.

Brett Martin is a GQ correspondent.

A version of this story originally appeared in the February 2020 issue with the title “The Incredibly Happy Life of TV's Favorite Grouch.”

PRODUCTION CREDITS:

Photographs by Jason Nocito

Styled by Mobolaji Dawodu

All clothes, Larry's own

Grooming by Johnny Hernandez using Dior Backstage Face & Body Foundation

Tailoring by Yelena Travkina

Produced by Connect the Dots

Originally Appeared on GQ