Improving treatment by helping immune system see cancer

Researchers using new technology to make cancer cells more visible to the immune system say it could lead to a future innovative cancer treatment option.

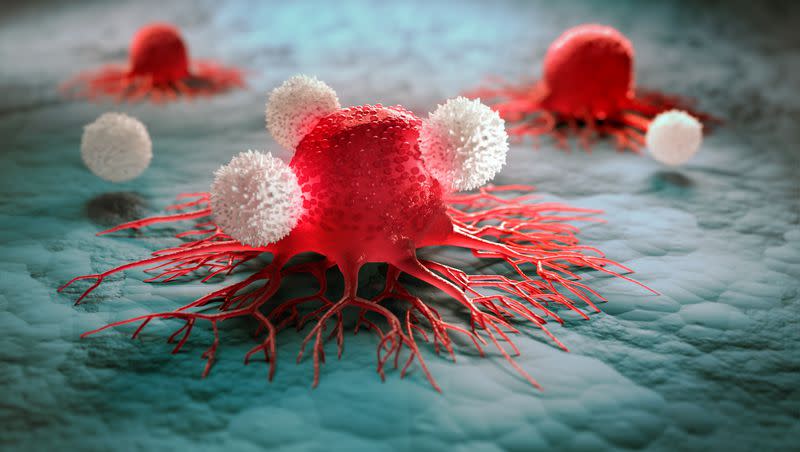

Cancer cells hide from the immune system, according to researchers at Hokkaido University in Japan, Texas A&M Health Center and the University of Missouri. To detect cancer, the immune system has to see the cancerous cells, which only happens if a certain type of molecule is present on the cancer cell’s surface. When cancer cells “face pressure” from the immune system, they shrink those molecules so they won’t attract the immune system’s cancer-fighting efforts.

The molecules are called Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class 1 molecules and they’re described in a news release from Hokkaido University as being on the surface of all human cells.

Researchers at the three universities have developed technology that significantly increases the volume of the MHC molecules in cancer cells, boosting their visibility to the immune system. They published their efforts in the journal PNAS, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Koichi Kobayashi, a professor at Hokkaido University, said the discovery could change how cancer is treated. “Our technology enables us to specifically target immune responsive genes and activate the immune system against cancer cells, offering hope to those who are resistant to current immunotherapy.”

Immunotherapy uses the patient’s own immune system to fight cancer.

The researchers tested their technology in animal models, finding that it shrunk tumors significantly and boosted the activity of the immune system’s cancer-fighting cells. Used with existing immunotherapy, they said, it “markedly enhanced treatment efficacy.”

They said that some of the cancer-fighting activity created hope the technology could be used in the future to treat cancer that has spread to other parts of the body, too.

Cancer research progress

Cancer is a worldwide target for research. Last week, The Jerusalem Post said a study from Haifa’s Technion-Israel Institute of Technology found cell typing based on expression of metabolic genes indicates how a patient will respond to immunotherapy.

Related

A new tool developed at the institute looks at metabolism in immune cells in the tumor microenvironment. Their findings are published in the journal iScience. The research involved cancer patients, rather than usual early studies in lab dishes and animal models, the researchers said.

Per the news article, “Since cancer cells and the immune system cells are found in the same environment, they are fighting over the same resources.” Determining their metabolic demands thus makes it possible to predict how well the immunotherapy will work.

Currently, cancer-fighting immunotherapy drugs are effective in about 4 in 10 cancer patients, the Post reported.

Meanwhile, in the United Kingdom, The Guardian this week reported on a clinical trial of a new messenger RNA, usually called mRNA, treatment to combat cancer. The treatment is being used on patients at Hammersmith Hospital in London and will evaluate the therapy’s safety and effectiveness against lung cancer, melanoma and other solid tumors.

The goal is to help the immune system recognize cancer cells and get fired up to attack them.

But the researchers warn that the work is in the early stages “and could take years before becoming available for patients.”

The article notes that nearly half of people in the U.K. will be diagnosed with cancer at some point. “A range of therapies have been developed to treat patients, including chemotherapy and immune therapies,” the article said. “However, cancer cells can become resistant to drugs, making tumors more difficult to treat, and scientists are keen to seek new approaches for tackling cancers.”