“My Imaginary Relationship With Layton Kor Got a Little Weird.”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This article originally appeared on Climbing

Arriving in Colorado in my cherry-red Dodge van, running my hands anxiously through my mullet, I pulled onto the campus in Fort Collins half awake and half dreaming of what lay in store for my new life in the mountains. It was 1989.

At 18, I was a serious and determined kid, crossing a threshold from my suburban existence in Illinois to a new horizon at the foot of the Rockies. Although I liked trolling the mall for girls and drinking behind the 7/11 as much as the next sleeveless boy, I'd never felt quite at home in the tracts of the burbs. I'd been scheming my escape since I was a junior in high school, when I hatched a weird mission to become a rock climber. I read some articles in National Geographic and knew about John Bachar, which I pronounced Bah-KAR as in Bacardi, and pumped iron in PE in preparation, but I'd never actually seen any rock climbing.

For my plan to succeed, I'd need to surround myself with those of like mind, and that's how I found myself at Colorado State sight unseen, and signed up for the Outdoor Adventure floor in Edwards dorm--a co-op designed to bring together students with similar interests and goals. Why they thought that would be a good thing is beyond me, as two-thirds of the floor was failing at the end of the semester, but that's another story. As I unloaded my belongings from my rank van, I just hoped somebody could show me a few knots.

It turned out that most of the denizens of Edwards 2nd SW preferred smoking pot and playing Nintendo to actual adventure, but still, a small group coalesced around the same philosophy Don Whillans' crew had found so helpful 30 years earlier: party hard, climb harder. In short order, we scaled many of the campus buildings by night, started bouldering above town at Horsetooth Reservoir, and began to dream up plans for the "greater ranges" (Eldorado Canyon, for example).

After only a few weeks, our inexperience combined with relentless teenage energy was like a race car drifting into the wall. It was only a matter of time before bones would start breaking, or worse. So in lieu of an actual mentor, we adopted a symbolic patron, a leader, a saint to whom we could dedicate our efforts and lay down our lives as young men often do.

I first heard his name during a slide show at the Mountain Shop adjacent to campus. Our R.A., Andy Meading, had gathered up the worthy to see Earl Wiggins and Katy Cassidy promote their new book, the classic Canyon Country Climbs. Their desert pics melted my suburban face off, while the Finger of Fate route on the Titan in Utah blew my mind. That thing is around here somewhere? I had never seen anything as majestic and bizarre as Castleton or Standing Rock, and attached to these incredible tower climbs was one impossibly cool name: Layton Kor.

Layton Kor. Like core. To the core. Back at the dorms, I couldn't stop prodding my more experienced friends about what it would take to climb something like the Titan. "Aid climbing," they said, but none of us had much idea what that was.

"What about this Kor guy? Do you guys know anything about him?"

My friend Scott Fitzgerald handed me the book CLIMB! by Bob Godfrey and Dudley Chelton, saying, "There's some stuff about Kor in there." I read and reread it over the next few days.

Kor states in his book Beyond the Vertical, "I grew up on a diet of [Hermann] Buhl, [Emilio] Comici, and [Ricardo] Cassin." For me, it was Kor, Erickson and Briggs, but mostly just Kor. At the end of the 1980s, American climbing was at a crossroads of sorts. The first sport routes had sprouted up under great controversy, but the steamroller that sport-climbing would become was still idling. Bouldering had just started to take on a life of its own, too. Our little crew, steeped in the storied ascents of the past, started practicing direct aid--first on the rock wall in the study room on our floor, then outside on cracks at Horsetooth and Lumpy Ridge.

That winter, as our skills on rock, ice, and snow grew, sometimes the other half of our philosophy--the party hard half--got in the way. So in the way, in fact, that for five weekends in February and March of 1990, I found myself reporting to jail for vandalizing a cop car one drunken night. Each Saturday morning, while my bros were gearing up for whatever adventure had been proclaimed the booze-soaked night before, I pedaled my bike over to the courthouse and turned myself in until Sunday night.

However, during one of those dark days, a seemingly mystical visitation occurred. The "Weekenders" program is really more of a sleep-away camp for losers than true jail. We'd spend the day doing public service and nights sleeping on cots in the basement of the courthouse. One night, after painting curbs all day, I was despondently leafing through a stack of ancient National Geographics in the lounge area when I flipped by a yellowed-out picture of the Titan. Wait, what? Desperately, I pushed the pages back until I found, "We Climbed Utah's Skyscraper Rock."

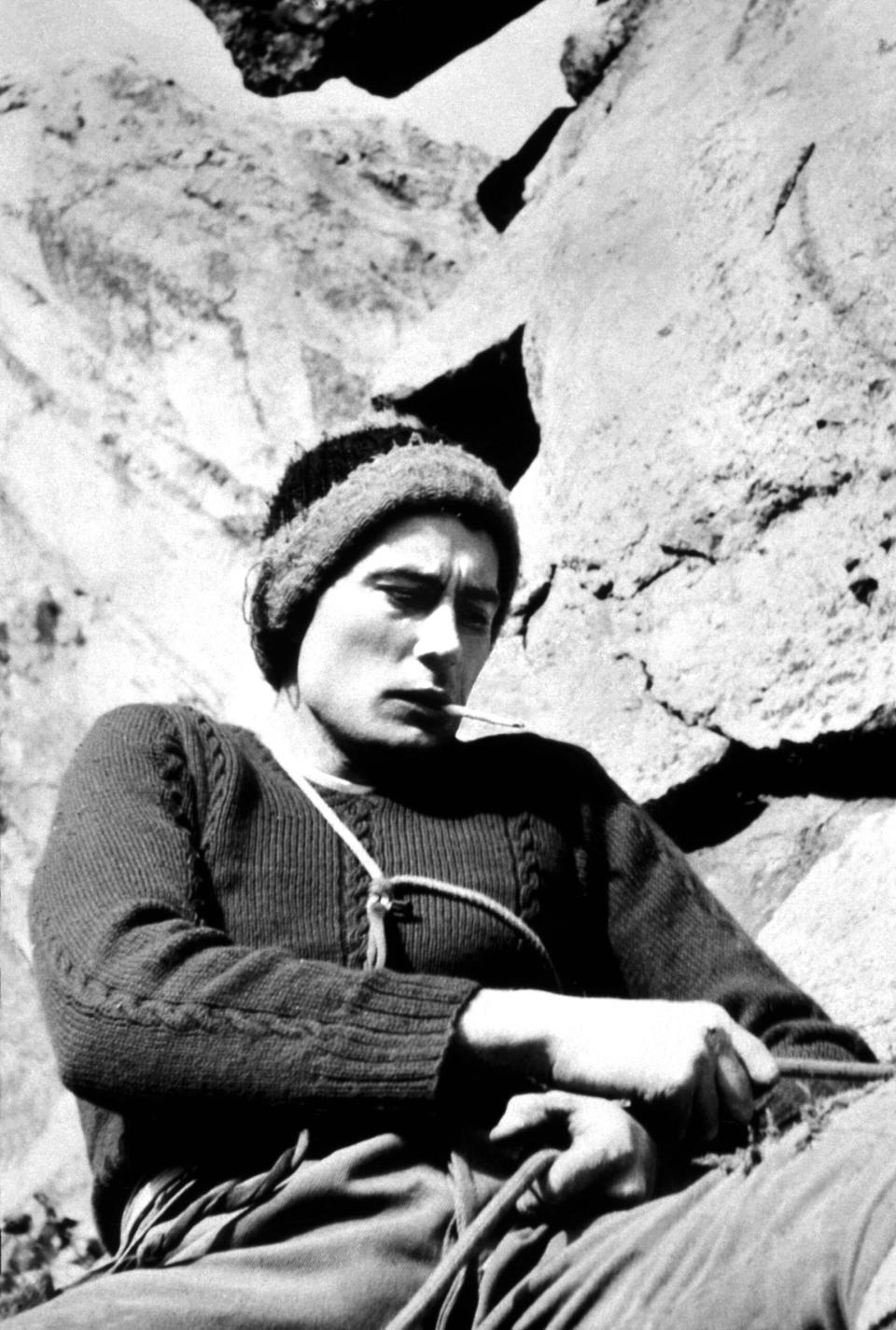

The 1962 article, by Huntley Ingalls and shot by Barry Bishop, chronicled the first ascent of the Finger of Fate on The Titan in Utah's Fisher Towers. In jail, I read about the FA of the Titan, and looked at classic saturated pictures of Kor and friends on the biggest, coolest tower in the desert. I looked around the room at a couple of pale, mopey men and pulled the magazine closer to my chest. This was mine. It was like a band that I discovered before it went big. That night I hid the issue on the bottom of the pile, and on the last weekend, I walked out with it. When I laid it before Scott, also a Kor devote, I jokingly whispered, "Behold."

For the next year or so, I will admit, my imaginary relationship with Layton Kor got a little weird. I became obsessed with not just climbing in general, but repeating Kor routes. I started signing Kor to the occasional "Do you want to climb tomorrow?" note left for my friends. Reading about his endless drive and energy, I vowed to climb every day if possible. I scrawled, "The mountains are my mistress" on the door to my room to symbolize my dedication, which, of course, did nothing to encourage actual female visitation.

I read Kor's book Beyond the Vertical over and over, and could quote it liberally and probably annoyingly. When Eric Bjornstad's seminal guidebook Desert Rock arrived on the shelves that summer, I read it like a novel, highlighting all the Kor routes for easy reference. The pages about the Titan became dog-eared and greasy.

Sometime in there, it occurred to me that despite deification, Layton Kor was, in fact, an actual human, and still alive somewhere, and therefore, could be contacted. The thought was shocking. It was well-known that he had given up climbing decades before, and for all practical purposes, fallen off the face of the earth. One day Scott and I asked our friend Larry Coates, a seasoned climber from Boulder, if he knew what had happened to Layton Kor. Larry thought that he was living in Glenwood Springs and was still a brick-layer.

I was self-aware enough to realize that my worship was partly tongue-in-cheek and based on a myth, and that reality might shatter the whole thing. Still...where's Glenwood?

*

The Dominoes guy pointed. "Yeah, just up there. Right at the end of that cul-de-sac."

A few days prior, I had been studying at the campus library when I walked past a bank of all the phone books in the state. On a whim, I'd looked up "Kor, Layton" in the Glenwood Springs book, and there he was! Layton Kor? In the phone book just like everybody else? I glanced up to see if anyone was as blown away as I was. I scribbled down the address and casually walked away whistling.

Days later, we were sitting in my dark, idling van just down the street from his house: two pilgrims about to reach their shrine.

"Let's come back tomorrow, dontcha think?" asked Scott.

"Yeah, he's probably sleeping."

It never occurred to us that we were flat-out stalking Layton Kor. It also never occurred to us that he might have a family--wife, kids, maybe a dog. I guess we just figured he was sitting in his house ready to welcome us in, pop some beers and regale us with tales of his ascents.

At about 10:00 the next morning, Scott and I, our copies of Beyond the Vertical tucked under our arms, simply rocked up and knocked on Layton Kor's door. A woman answered, "Can I help you?"

"Uh, is Mr. Kor home?" Mr., that's good, show respect.

"Which one?"

"Uh, which one?" Which one? WHICH ONE? THE Layton Kor, first ascent of Yellow Spur, first winter ascent of the Diamond, the Eiger...

"Jamie or Layton?" she offered.

Oh, his son, right. "Um, Layton?"

"Layton doesn't live here any more."

Probably seeing the light drain from our eyes, the woman, Layton's recent ex-wife, Joy, invited us in to sit awkwardly in her living room. She was nice but to the point as she asked us what we were doing on her doorstep asking after her now ex-husband. We mumbled about just wanting him to know that he was still relevant to some young climbers ... even though everyone is into sport climbing now ... which we think is lame. We wanted to get him to sign our books, and ... just meet him.

She let us dribble off. "Well, you just missed him. He went to the Philippines a couple months ago. Some of his stuff is here so he will be back. I'll mention you came by."

Sweetly, Joy actually chatted with us for a while and asked us to climb with her the next day. As we left, I asked her if this had ever happened before.

"Usually, they call first," she said, and laughed.

The next day Joy, a nurse, was called for work instead, and we headed back to Fort Collins. The flame dimmed slightly but probably for the better. Layton Kor was only a man, had an ex-wife who might not think he was such a great guy. No problem. His legacy is in his climbs. That's where we would worship.

By spring break of 1991, we felt we were ready for a climb like the Titan. At that point, it had probably not seen a dozen ascents, and half of those were by other illuminati besides Kor. The Fishers were still a quiet place where you'd rarely see any climbers past the relatively benign Ancient Art.

Scott and I set up camp near the base and started up the grooves of the first pitches. Neither of us had pounded much iron, and techniques like tying off pins were merely ideas from stories about the old days in Yosemite or Black Canyon. Being so thoroughly steeped in the lore seemed to pay off as we went higher. We goofed off for the camera on the stances we recognized from the photos in Nat Geo and were naively delighted to find bolts from Kor's 1962 ascent, not realizing what death-bombs they had become. Day one went off without incident, and we descended fixed lines to the ground congratulating one another on our radness.

The final bolt ladder to the summit was still primarily the original "bolts," which were just one-inch nails pounded into an expanding lead sleeve with a poorly designed homemade hanger. I blithely high-stepped up the ladder, caught up in that same problem so many of Layton Kor's partners had complained about: his massive reach. As I strained to clip a newer bolt, the one holding me blew and sent me and my rack of iron winging about 20 feet nearly back to the belay. Once I righted myself and realized I was fine, I quickly unclipped my new religious relic from the rope and held it up to show Scott: a genuine homemade Kor bolt.

Moments later, I was teaching myself how to place a bolt with our borrowed kit, and soon, on the summit. Scott and I took the standard photos and felt the same strange mix of elation, relief and mild disenchantment that climbers have always felt on summits. We're here, now let's get the hell off. Yet I also felt a palpable connection between those faded photos from the past in that National Geographic, and my future as I looked across the landscape at the rest of the Fisher Towers and into Castle Valley. I wanted to be on top of them all.

In the next few years, I fell into a pattern that hit the same beats of so many of my idols, including Kor. I worked my way up through the grades at local cragging areas like Eldorado Canyon and Lumpy Ridge. Like those of Kor's generation, I viewed these routes as "practice" climbs' for ethereal greater ascents in the future. Bouldering had become a sport in its own right, but I never shook the attitude that the blocs were merely training for the bigger stuff. Forays back to the desert, often solo, had me repeating some of the hardest aid climbs there, yet no ascent was even finished before I was thinking about the next.

While I was no longer blindly devoted to Kor, I was still steeped in the history of climbing. I returned to Beyond the Vertical periodically. It fascinated me to think a time when the most classic 5.9 routes in Eldo had yet to be done. The sizzle of possibility must have been intoxicating.

Each time I got absorbed in the pages, I found in myself the ability to read between the lines more and more. The book is somewhat epistolary in that much of the narrative is driven by letter-like accounts of climbs by Kor's many partners. Themes run pretty clearly: a man driven, nervous energy, pushy, absorbed in leading everything, burning through partners. Although in college I had found all these qualities admirable, with more maturity, I started to see them as potentially sinister, especially as I started to recognize them in my own personality.

While I had originally glossed over the chapters in the book that pointed towards Kor's eventual disillusionment with climbing, now my own quest for big answers brought new light to his eventual religious conversion. Looking at my dirtbag life in my late 20s--no money, no girlfriend, no roots--I started to wonder if I should find Andy, my old dorm RA who took me toproping for the first time, and punch him in the face.

Instead I dusted off my English degree and got a job teaching high school--a good, noble pursuit with intrinsic rewards and impossible challenges just like climbing. With no place to store my books in my shared apartment, I transported all my guides and climbing volumes, including the most sacred text, to a shelf in my classroom.

I guess I thought some troubled kid might be inspired by them to climb, but I turned out to be the troubled kid. Particularly rough days had me sitting on the little reading couch near my books, leafing through the tomes and wishing for summer.

Reading about Kor quitting had in college felt like a mild betrayal, but now I was becoming a weekend warrior. Yet, even as I held down my teaching job, bits of information started to blip on the radar saying that Kor was climbing again. I was quietly relieved of a tension I didn't even know I carried. Kor had returned to the fold!

I lasted five years before I quit my comfortable teaching job and gave into a harder life with hard climbing on multiple continents. This time I made peace with the sacrifices. I decided that climbing, and stalking the wild places where cliffs reside, is a noble and life-affirming pursuit even if it goes against the social grain.

*

When I place the call, I'm standing in the master bedroom of a giant deserted mansion that I am painting in Aspen. I become acutely aware of the empty echo in the room as the awestruck boy I used to be starts to stammer. "Hi, Layton? My name is Chris Kalous. Ron Olevsky gave me your number..."

It's August, 2011, and 21 years have gone by since I first heard his name in Fort Collins and became obsessed with his legacy. I am finally contacting the real man.

I detect a bit of embarrassment and distress in the quiet voice on the other line. Fighting protracted health issues, Layton is just not feeling well enough for any type of interview. He is simply too tired, he tells me. Nervous and a bit shaken, I thank him anyway. We talk for no more than 45 seconds.

I am disappointed for a moment, but the realization soon settles in that I may never know the man, and that may be for the best. I've spent my life pursuing climbing with a passion similar to what I imagine coursed through Layton Kor's heart back in those early days in Eldo. It has led me around the world, often in his footsteps, to climb in many of the same ranges and see the same vistas. He is a wholly mythological figure to me, created out of tiny scraps of information. I molded him to fit an image that affirmed my beliefs and inspired me to be better. Inspiration is a gift he's unwittingly, and perhaps unwillingly, given to generations of climbers, and for it I am grateful.

*

Chris Kalous is a climber, house painter, and internet personality. His bi-monthly podcast can be found at enormocast.com.

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.