All About Ice Swimming, the Extreme Sport Where Athletes Compete in Sub-Freezing Water

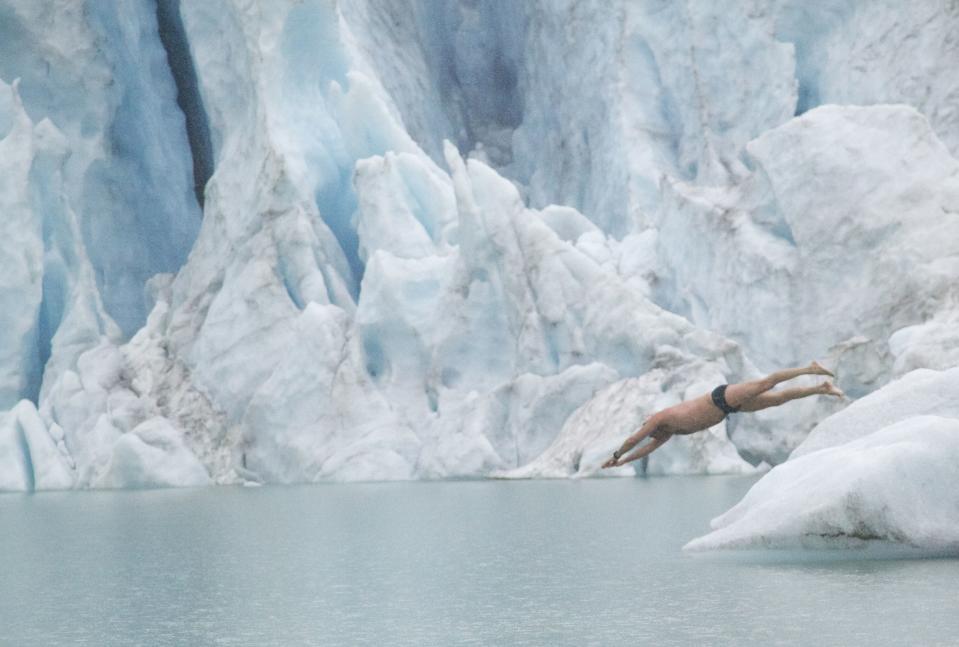

In early 2014, Ram Barkai took a trip to Antarctica. There, Barkai and five others did what most would deem unthinkable: They swam in the Southern Ocean, which was 30 degrees F. Yes, that is below the freezing point of water.

“There was a lot of floating ice of various sizes,” Barkai, 60, tells SELF. “We did swim into ice every now and then, but it’s fine because you’re so frozen you don’t even feel or notice it.”

Thus is the surreality of ice swimming, arguably the most extreme adventure sport on the planet with a small, yet growing contingent of participants. The most recent Ice Swimming World Championships, held last year in Burghausen, Germany, drew 120 participants who swam 1 kilometer (about 0.62 miles) in 36.5 degrees F water—without the warmth of wetsuits.

"I've always been attracted to the mental challenge rather than who has the biggest muscles," says Barkai, ice swimming Guinness World Record holder, founder of the International Ice Swimming Association (IISA), and unofficial father of the sport. And when it comes to mental challenges, ice swimming, with its inherent risk, below-freezing temps, and excruciating recovery process, certainly fits the bill—and perhaps even takes the cake.

In anticipation of the upcoming ice swimming season, which kicks off in November with events in Latvia and Russia, we asked Barkai to explain the history of the sport, what it feels like to swim in such horribly cold conditions, and the physical and mental strength required to survive it all.

Ice swimming became an organized sport in 2009, when Barkai founded the International Ice Swimming Association.

Israel-born Barkai, who grew up by the water and has “always felt very comfortable” in it, started swimming seriously at age 40. Shortly after, he took his new passion to the ocean, swimming in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of his current home in Cape Town, South Africa, which marked his introduction to cold water swimming. “The water is cold all year round,” says Barkai. With long-distance ocean swimming, particularly off the coast of South Africa, “people are worried about sharks, but I say swim for 30 minutes and you will pray for a shark to come ‘rescue you’ because you are so cold,” he jokes.

In 2008, Barkai went to Antarctica with an expedition group and swam 1 kilometer in 32 degree water, setting a still-standing Guinness World Record for the “most southerly swim.”

Ice Swimming 2.jpg

International Ice Swimming AssociationAfter the experience, “I realized there are a lot of urban legends out there [related to ice swimming accomplishments and records],” he says. “One way to determine truth is to have structure and put parameters in place and encourage people to record their efforts.” Thus, the International Ice Swimming Association was born in 2009, and by default, the sport of ice swimming, too. [Note: Ice swimming is not the same as winter swimming, a separate sport covering shorter distance competitions in a wider range of cold water temperatures.]

At its core, ice swimming is a minimalist—but extreme—adventure sport.

Per IISA definition, the rules of ice swimming are specific, yet simple. The sport can take place in a pool, or natural body of water, as long as the water temperature is 41 degrees F or less. Swimmers must wear a standard one-piece swimsuit that doesn't extend below the swimmer's knees and doesn't go beyond the swimmer's shoulders or above the neck line. Wetsuits are not allowed but competitors can wear one cap and one pair of goggles. For safety’s sake, there are just two official race distances: 1 kilometer and 1 mile. Barakai said that this is to make sure swimmers' ambition doesn't out pace what can be done with relatively manageable risk. “Otherwise, some people would probably try to swim longer distances [that are unsafe],” he says. The kilometer race is about speed (there’s a 25-minute cut-off), and the mile is more about the adventure aspect of ice swimming, like traveling around the world to swim in “amazing places,” he says.

In total, IISA has several thousand members from 60 countries, says Barkai, though not every member has completed the sanctioned distances. According to Barkai, 272 people have completed the ice mile (as verified through IISA), and more than 500 have completed the kilometer. The biggest competition in ice swimming is the World Championships, which will next be held in March 2019 in Murmansk, Russia, with other competitions scheduled in the interim. Barkai's ultimate goal, he says, is to eventually make ice swimming a sanctioned Olympic sport.

Ice swimming is an inherently dangerous sport—you're basically asking your body to perform in an extreme environment that it's not meant to survive in.

The sport is dangerous for several major reasons, Melissa Leber, M.D., assistant professor of orthopedics and emergency medicine at The Mount Sinai Hospital, tells SELF.

The first: risk of hypothermia. “You could get too cold and blood flow could stop going to your extremities,” she explains, which could potentially cause long-term damage. Hypothermia can also alter your state of mind—“it might be like swimming while being intoxicated,” she says—which could increase your chances of drowning. Lastly, hypothermia could trigger cardiac arrhythmia, or irregular heartbeat, which could then trigger cardiac arrest.

Another big risk is laryngospasm, or sudden spasming of the vocal cords, which make it very difficult—if not impossible—to breathe, explains Leder. This can happen when your body is subjected to an unexpected, dramatic drop in temperature (like going from a comfortable temperature to jumping into 40-degree water, for example), and typically occurs within five minutes of the initial shock.

These risks are why safety is taken seriously in the sport. There is a medical doctor on-site who records the swimmers' medical history before the competition and "approves" them to swim. According to ISSA rules, all swimmers must also have their heart rate, blood pressure, and resting EKG taken 30 minutes before swimming; there's also another exam post-swim. The doctor is also on hand should there be any need for medical assistance during or after the competition.

Both ice swimmers and observers (IISA officials who are responsible for monitoring safety and adherence to the sport's official rules) need to learn the signs that a competitor is in trouble. A couple things observers look for in the water: If a swimmer seems to be sinking or if they're going through the motions of their stroke but not moving forward, it could be because they can't feel the water anymore. If a swimmer seems confused when they get out of the water, that's another danger sign. As a swimmer, another can't-ignore signal is worsening vision.

“It will start to feel like someone is dimming the lights on you,” explains Barkai. “It gets to a place where you get a tunnel vision of light where you can’t see any periphery.” Then, the tunnel will “start to shut down,” he says. At that point, “you know you need to get out [of the water]."

In the nearly 10 years that ice swimming has been a sport, “we haven’t had one death,” says Barkai.

That said, because of all the aforementioned risks, Leber says you should not attempt ice swimming on your own and should always check with your doctor before trying an activity so inherently risky.

The post-swimming recovery process, in some ways, can be worse than the swim itself.

Diving into cold water is an immediate shock to the entire body, says Barkai. But the process of rewarming is equally, if not more, agonizing. The cold water makes your skin “very sensitive,” says Barkai. His support crew has special instructions to handle him gently when he emerges from the water.

Ice Swimming 3.jpg

“You feel like there is ice flowing in your veins,” says Barkai, and regaining the sensation in your extremities can feel like “someone is pulling out your fingernails with pliers.”

Ice swimmers could get “burning pain” in their hands and feet as they rewarm, Leber confirms. “It’s painful more than anything.”

Barkai says sport protocol has swimmers take off their cap and goggles, and roll down their swim suit to dry the skin underneath. Then, they head to a dry sauna—or, if there’s no sauna nearby, a warm car with the heater on full blast—where they’re wrapped in blankets. After the swimmer returns to full coherency, they’re typically moved to a hot shower or hot tub for further rewarming. Coming out dazed and incoherent is common for many ice swimmers, Barkai says.

Ice swimming requires a combination of ironclad physical and mental strength.

In order to survive ice swimming, you have to be a good swimmer—no exceptions, says Barkai. “Because it’s such a hostile environment, you need to be able to cover distance in a reasonable time.”

Yet because the distances themselves are relatively short, ice swimming, Barkai believes, is, at its core, "more mental than physical." Unlike other sports, where physical pain sets in after a certain amount of time, with ice swimming, “the pain starts immediately, and you have to manage it immediately because it just gets worse and worse,” says Barkai. “If you are not mentally prepared to handle that, you will struggle.”

Training and experience helps greatly with this, says Barkai. That’s why when he was training for his swim in Antarctica, he swam in the Atlantic Ocean every single day for 45 minutes, no matter the waves and wind. This helped “push away any mental weakness.”

Another strategy of Barkai's is to "under-think." “Getting into ice water is a scary thing,” admits Barkai. “You undress from very warm clothing until you’re basically naked and then you dive into ice.” But the more time you spend standing on the side contemplating the swim, the less likely you’ll be to actually get in and do it. Barkai has a personal rule (that he’s never broken, by the way), that once he’s undressed, he counts to 3, and must jump in by 3.

And lastly, there’s the acceptance approach. “There’s nothing you can do about the cold,” says Barkai. He tells himself: “There are no tricks, so don’t worry about it. Push the cold away and focus on other things.”