What Is Hydrocephalus?

Medically reviewed by Nicholas R. Metrus, MD

Hydrocephalus occurs when there is a build-up of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in the brain. A network of connected cavities within the brain—called the ventricles—produces CSF. CSF helps cushion and nourish the brain. In people with hydrocephalus, the ventricles become larger and fill with more CSF than is normal.

Hydrocephalus can affect people of any age, but it is most common in infants and older adults. It affects roughly 1 in 1,000 babies born in the United States. A specific kind, called “normal pressure hydrocephalus” (NPH) affects about 40 in 1,000 people over age 80.

Types

There are two main types of hydrocephalus: communicating and non-communicating (also called obstructive). Communicating hydrocephalus can be divided into two sub-types: normal pressure hydrocephalus (NPH) and hydrocephalus ex-vacuo.

Communicating: This type occurs when CSF is blocked after it flows out of the ventricles. It is called "communicating" because CSF can still go from ventricle to ventricle.

Normal pressure hydrocephalus: This type generally only affects older adults, and usually after a stroke or injury. CSF drainage becomes blocked over time, slowly causing a build-up. Enlarged ventricles due to CSF build-up eventually push on the brain.

Hydrocephalus ex-vacuo: This type occurs when a medical event such as a stroke or injury damages the brain, causing the brain matter to shrink. In response, CSF fluid builds up in the excess space.

Obstructive (non-communicating): This type occurs when CSF is blocked in the areas connecting the ventricles.

In addition, hydrocephalus is distinguished between being primary (also called "intrinsic" or "congenital") and secondary (also called "extrinsic" or "acquired"):

Primary hydrocephalus is typically present at birth, occurring from developmental problems with the brain, ventricles, and related structures. It may also sometimes be called “congenital hydrocephalus.”

Secondary hydrocephalus, which can happen at any time of life, is caused by some problem that obstructs the flow or reabsorption of CSF, like a brain tumor.

It’s also important to distinguish a chronic hydrocephalus from one that emerges quickly, termed “acute hydrocephalus,” as they have different treatment considerations.

Hydrocephalus Symptoms

Symptoms of hydrocephalus can vary based on age, underlying cause, other medical issues, and severity.

Infants

Some possible symptoms in an infant could include:

Abnormal increase in head size

Bulging soft spot (fontanel) on the head

Difficulty feeding

Vomiting

Irritability

Downward deviating eyes

Older Children and Adults

Hydrocephalus in an older child or an adult can look a little different, although some of the same symptoms, like seizures, sleepiness, and irritability, might also be present. For example, they might also have:

Declining school or job performance

Symptoms of dementia, including changes in cognition or personality, among other

Vision problems

Chronic headaches

Poor coordination

Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

For adults with NPH, the three most important symptoms to consider are:

Difficulty with coordinated walking, symmetrically, with feet feeling “stuck”

Cognitive impairment

Urinary urgency or incontinence

These may take months or years to develop.

Acute Hydrocephalus

Acute hydrocephalus is a life-threatening medical emergency that needs immediate treatment. It can cause the brain to be squashed against the skull, called “brain herniation.” This can lead to serious symptoms like coma or cardiac arrest.

What Causes Hydrocephalus?

CSF flows in one direction through a complex pattern of ventricles and channels until it is released into a space just outside the brain and ventricles (called the subarachnoid space). From there it is absorbed into blood cavities that eventually flow back to the heart.

If anything blocks this normal flow, CSF can build up, enlarging the size of the ventricles. Thus, any kind of obstruction in the ventricles or subarachnoid space can lead to hydrocephalus, as can anything that blocks CSF from being absorbed back into the blood.

Primary Hydrocephalus

Many children born with primary hydrocephalus have known medical genetic syndromes or developmental birth defects. In these cases, the brain and ventricles might not develop normally before birth. Some of these include:

Dandy-Walker syndrome: A condition that occurs in utero causing the cerebellum (the part of the brain located at the back of the skull) to not develop normally

Spina bifida: A birth defect that causes malformations of the spine

Chiari malformations: Malformation of the bottom part of the brain that causes part of the brain to bulge through the back of the skulls

X-linked hydrocephalus: A genetic form of hydrocephalus

Tuberous sclerosis: A rare, genetic disorder that causes non-cancerous tumors to grow in the brain and around the body

Sometimes infants are born with hydrocephalus even when no known genetic or developmental cause can be found.

Secondary Causes

In the United States, hydrocephalus after a brain bleed (which can be caused by injuries or complications of other conditions) is the most common kind of secondary hydrocephalus in children. Most of these infants were born premature, which puts them at high risk of such a brain bleed (called an “intraventricular hemorrhage”).

Infections such as meningitis are another key cause. Inflammation and debris from infection may cause blockage or scarring of the ventricles.

Trauma is another important cause. For example, of former members of the military who suffered a moderate to severe traumatic brain injury, up to two-thirds have long-standing hydrocephalus.

Hydrocephalus can also occur from cancer, either because the cancer is blocking the flow of CSF or because the cancer itself is making larger than normal amounts of fluid.

Causes of Normal Pressure Hydrocephalus

The cause of NPH is less clear, which is why it is sometimes referred to as idiopathic normal pressure hydrocephalus, or iNPH. Idiopathic means that the cause is spontaneous or unknown. Scientists hypothesize that irregularities in the flow of CSF may increase physical stress on brain tissue and blood vessels. This may lead to reduced blood flow to the area, inflammation, and metabolic changes that lead to the symptoms associated with hydrocephalus.

Diagnosis

As part of diagnosis, your healthcare provider (usually a neurologist, or a doctor who specializes in the brain and spinal cord) must rule out other conditions that can cause similar symptoms or imaging findings.

Taking a thorough medical history and conducting a physical exam are key parts of the diagnosis process. These can give a lot of clues that some type of neurological process is going on. Doing a special exam to look at the back of the eye—called a fundoscopic or ophthalmoscopic exam—also gives clues about increased pressure inside the skull.

Testing

Sometimes an ultrasound of the head is helpful as part of the initial diagnosis if hydrocephalus is suspected. It is an inexpensive imaging test that can be performed right at the bedside.

However, more detailed imaging is needed as well. These tests can confirm hydrocephalus, and also give more information about its severity and specific characteristics, including a potential underlying cause (e.g., a brain tumor).

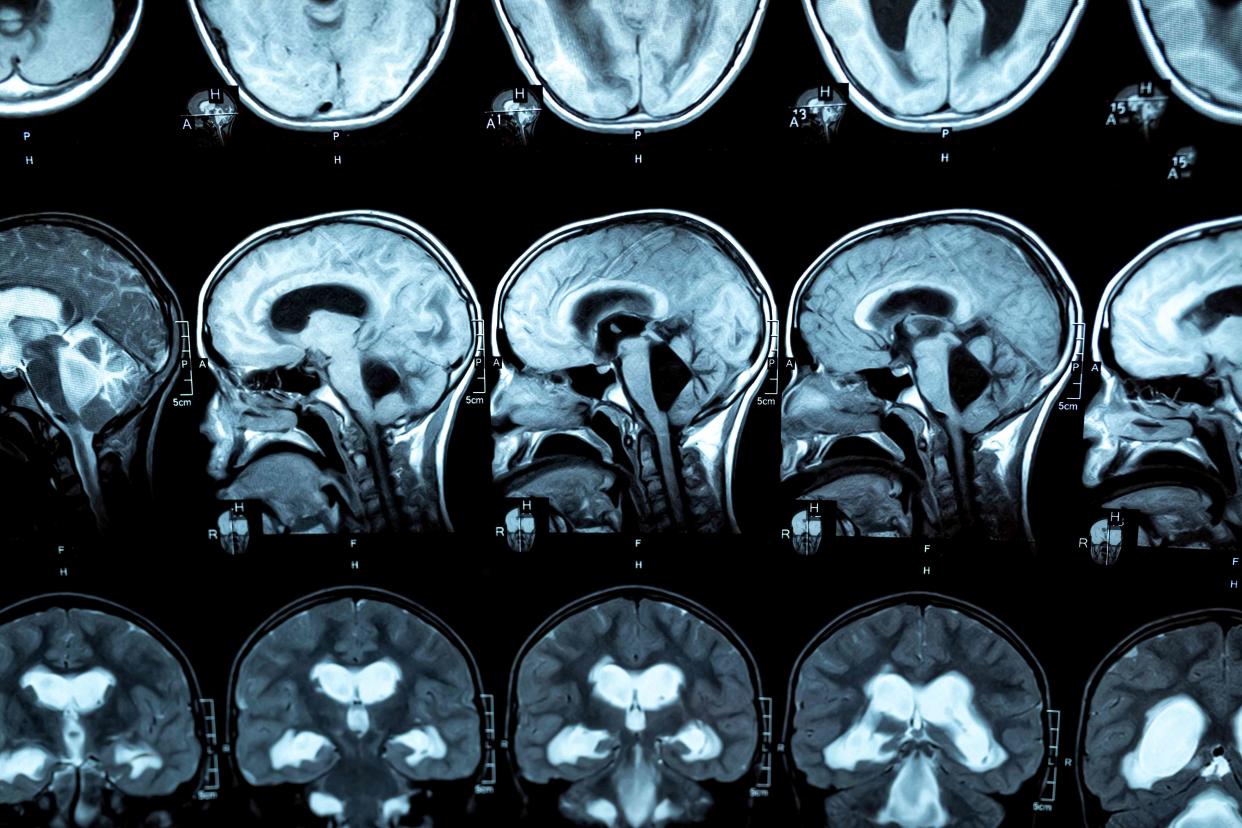

Typically, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the best imaging technique to get detailed information about the nature of the hydrocephalus and help plan for treatment. However, acomputerized tomography (CT) scan can also give some helpful information if MRI is not available.

Neurologists may also use a lumbar puncture to get more information about hydrocephalus. For example, it may show that the pressure of your spinal fluid is normal as it comes through the needle, such as in NPH. However, it may need to be used cautiously if you are at risk of having problems from high pressure on the brain.

Additional tests may be needed in specific circumstances, such as blood cultures to test for hydrocephalus with possible underlying infection, or specific genetic tests in an infant born with hydrocephalus.

Treatments for Hydrocephalus

Treatment for hydrocephalus can vary based on its underlying causes, severity, and patient age. The goal is to stabilize you in the short term but eventually address the underlying cause.

Non-Surgical Options

Some sort of surgical intervention is usually needed to treat hydrocephalus. However, sometimes a surgery might not be able to take place right away, or you might be at very high risk from surgery. Some potential non-surgical treatments include:

The drug Diamox (acetazolamide), which is a diuretic that can help reduce fluid build-up

The drug Osmitrol (mannitol), which is used to decrease intracranial pressure and brain mass

Hyperventilation (making you breathe faster), which can decrease your intracranial pressure and relax your brain

One or more of these may be particularly important if you have very high pressure inside the brain.

Procedures and Surgeries

Some procedures for hydrocephalus temporarily remove some of the excess CSF and reduce symptoms. For example, this might mean performing repeating lumbar punctures—commonly called a spinal tap—which is when a needle is inserted between two vertebrae to drain some CSF.

However, more permanent treatment requires surgery. In some cases, the surgeon may be able to simply remove the source of obstruction, such as a tumor, to correct the hydrocephalus.

However, most of the time surgeons need to surgically implant some sort of shunt to help drain away excess CSF. The surgeon places a flexible tube so that it can drain from inside a ventricle and guide the CSF to another part of the body, such as the space around the organs in your belly. This kind of shunt, called a ventriculoperitoneal shunt, is the most common type.

Fewer patients may be able to be successfully treated with a different procedure, called endoscopic third ventriculostomy. This less invasive procedure uses a small flexible tube, a tiny camera, and small instruments to create a space where the third ventricle can drain.

Co-Occurring Conditions

Epilepsy is one of the most common co-occurring conditions in people with hydrocephalus. For example, of people who have had shunt treatment for hydrocephalus, around 20% will still have symptoms from epilepsy. In addition, other neurological problems may not completely resolve.

Infants born with congenital hydrocephalus also often have a co-occurring condition, such as spina bifida.

Living With Hydrocephalus

The outlook for people with hydrocephalus varies widely, partly depending on the cause and rapidity of diagnosis.

Many infants born with severe hydrocephalus are likely to have brain damage and long-term physical disabilities, and some even die from their related medical conditions or from medical procedures to treat the hydrocephalus. However, many people with less severe disease go on to lead relatively healthy lives after surgical treatment.

Ventricular shunting is effective at treating symptoms in about 60% to 80% of people with NPH. In some people, symptoms like dementia and headache completely go away. However, prompt diagnosis is critical, as people don’t respond as well to shunting if they have had long-standing symptoms.

Although many people do well with their shunts, some shunts do eventually malfunction or fail. It’s important to seek immediate medical care immediately for any recurring symptoms of hydrocephalus.

For more Health.com news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Health.com.