The Hudsucker Proxy —Yeah, That's Right, The Hudsucker Proxy —Is the Coen Brothers’ Most Underrated Film

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

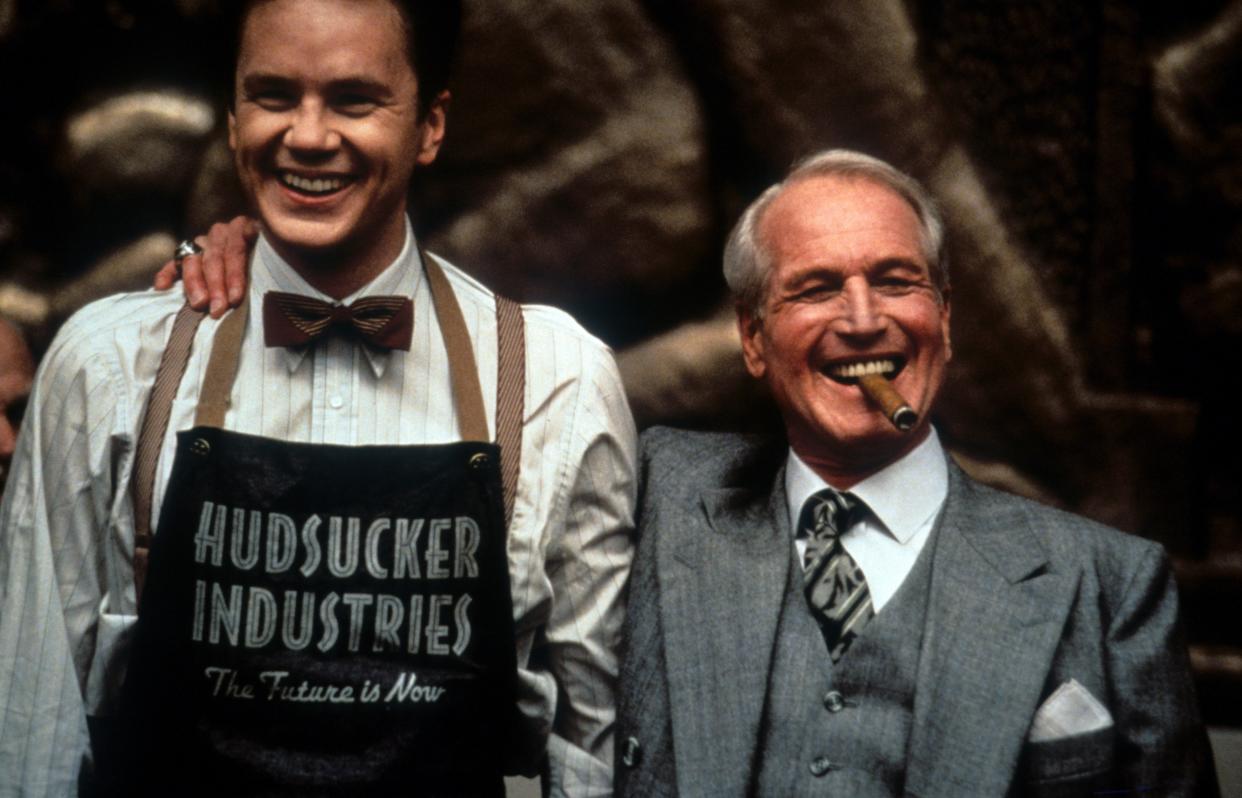

Warner Bros./Getty Images

If there’s one Coen Brothers milestone people are likely to celebrate this year, it’s the 40th anniversary of the pair’s first feature, Blood Simple, which made its debut at the New York Film Festival in the fall of 1984. Their remake of the 1955 dark British comedy The Ladykillers, which turns 20 in March, probably won’t get the same fanfare—which is reasonable, since it’s simply a bad movie. Yet, it would be a shame if the thirtieth anniversary of their most underrated film, The Hudsucker Proxy, went unnoticed.

There’s something interesting about the Coens’ two flops that came out in years that ended with a 4. The Ladykillers is a mess, but they followed it with the 2007 Best Picture-winning adaptation of Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men, which led into an unimpeachable run of movies including A Serious Man, their remake of True Grit, and Inside Llewyn Davis. There’s a similar narrative with The Hudsucker Proxy. After it was mostly panned by critics and ignored by moviegoers, the siblings gave us Fargo, The Big Lebowski, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, maybe their most beloved streak of films overall. The big difference is The Hudsucker Proxy, unlike The Ladykillers, shouldn’t be considered a bridge to better offerings; it should be counted among them.

But it isn’t. At least, not as much as it should be. I blame it on the year it was released. 1994 was the year when it felt like the word “indie” first started getting overused by the mainstream press, more often to describe an aesthetic than an ethos. This was the year of cheaply-made classics Pulp Fiction and Clerks, but also big-budget ones like Speed, The Crow, and Natural Born Killers. Hardly scrappy, independent releases—but the vibe of all those films, as well as the stars, and even the soundtracks (all filled with post-punk luminaries, Wax Trax! Records alumni, and even a little Leonard Cohen for good measure) felt designed specifically for Gen. X audiences.

The Hudsucker Proxy, on the other hand, looked like it was made for Boomers or even their parents. And while people today who have been raised to (think) they know everything and can learn whatever they want by scanning Wikipedia or watching a few TikTok videos, the promise of a screwball comedy mixed with a little bit of magical realism, starring Tim Robbins, Jennifer Jason Leigh, and Paul Newman in one of this finest late-era roles, seemed for—in the words of the New York Times Grunge Lexicon—lamestains confined to the harsh realm. The audiences wanted the Mighty Ducks shooting knuckle pucks and Tom Cruise and Brad Pitt as hot vampires—not Jennifer Jason Leigh talking fast with a Mid-Atlantic accent like she’s going to report one more story with her ex-husband Cary Grant.

A film like The Hudsucker Proxy failing when it was released was simply bad timing. But the thing about good films that are released at the wrong moment is that, sooner or later, they’re rediscovered and looked at in a different light. In this case, we have the Coens' entry into the canon of Boomer morality tales, a micro-genre of films from the first-half of the ‘90s that were billed as comedies, so a lot of people went looking for laughs and not deep existential questioning. These were movies that asked if all that “Greed is good” stuff from the previous decade was really the way to go. 1990’s Joe Versus the Volcano, Albert Brooks' Defending Your Life and Steve Martin’s L.A. Story the following year, and another film starring Robbins, 1992’s The Player—all of these films playfully ask what the point of everything is. Tom Hanks, as the titular Joe who is going to jump into a volcano, thinks he’s going to die so he finally starts to live. Albert Brooks plays a guy who dies and wakes up in the afterlife, where he has to defend his actions on Earth. The Hudsucker Proxy, on the other hand, wrestles with that old idea of “losing your soul.”

Robbins plays a small-town rube with a good heart. He’s proudly from Muncie, Indiana, the city where husband and wife sociologist team Robert and Helen Lynd conducted their 1920s studies of what they’d go on to call “Middletown,” the quintessential small American city. Hudsucker takes place in the last weeks of 1958, and Eisenhower’s America is made to look a lot like it was designed by Fritz Lang, all cold, clean, and modern. Just shy of a decade earlier, in January 1948, The New Yorker published John Cheever's story “O City of Broken Dreams,” in which a family travels by train from their own fictional Indiana Middletown to New York because some big-city producer has led them to believe the husband, a bus driver, has the chops to make it as a playwright, even though he’s only written the first half of one play. They quickly find how unrelenting and cruel a place like Manhattan can be, and that’s how the tale of Norville Barnes from Muncie starts. He’s a big, sweet goon who has an idea he’s sure will change the world, and in true Coens fashion, it’s simply a picture of a circle. The first time you see it, the words of the great Daffy Duck come to mind: Boy, what a rube.

But it turns out that Norville isn’t such a rube—he’s just an American guy with a big idea. An idea that turns out to actually be something more than just a gag, but I won’t spoil what the circle he’s drawn turns out to be. American history is filled with people known for coming up with one great idea, whether it’s Saumel Morse and his code or the Wrights and their flying machine. We tend to champion those people and their “American ingenuity,” but sometimes overlook the darker side of the money and fame it may bring. Norville doesn’t realize it, but he’s being set up for a fall. The only reason his circle makes it off the paper and onto production lines is because Newman’s Sidney J. Mussburger and the other stockholders at Hudsucker Industries want to tank the company stock so they can repurchase it all for chump change after the president, founder, and namesake unexpectedly jumps out the window from one of the top floors of a very high building. The stockholders don’t expect Norville to actually succeed, but then he does, and the swell guy from Muncie quickly switches over from the light into the darkness. It goes to his head and he’s content for a moment, but then he panics when he realizes that he doesn’t know how to replicate his success. How low is he willing to go for more?

There are Coen films that might deal with more personal themes—grappling with trying to write what you want and finding commercial success after becoming a critical darling in Barton Fink, the semi-autobiographical Minneapolis suburbia of A Serious Man. But coming after their first string of acclaimed movies all in a row, and just as the brothers were approaching or hitting middle-age—Joel turned 40 in 1994, Ethan is three years younger—Hudsucker feels like their most introspective. It’s a story of a person literally from the middle who gets to what the rest of America would consider “the top.” He’s in the office on the highest floor and a million miles away from Muncie, Indiana. He loses himself—but in a rare glimmer of hope in the Coens' sometimes unforgiving universe, he’s able to find his way back. Not to Muncie, but to wherever it was he last had his soul.

The movie has a happy ending, something that felt out of place in 1994. Vincent Vega walks out of the diner at the end of Pulp Fiction, but the viewer knows we’re seeing the middle of the story, and John Travolta’s character ends up dead on a toilet in Butch’s apartment. Woody Harrelson and Juliette Lewis as Mickey and Mallory Knox escape the cops and start a family at the end of Natural Born Killers —but they’re still both lunatic mass murderers. There isn’t much to compare The Hudsucker Proxy with from its class of 1994 movies except one other film that interestingly also stars Tim Robbins and was also a box office bomb when it was first released. Today, that movie, The Shawshank Redemption, is widely considered one of the greatest ever made.. I don’t think The Hudsucker Proxy is necessarily in that league, but it’s certainly far better than the reputation that’s stuck with it for the last 30 years.

Originally Appeared on GQ