Housing development Bel Vista’s recipe for a healthy and happy life

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

No mere nostrum, modesty could be prescribed today as the key to happy living. Our current culture of ostentation has engendered recommendations for possible antidotes in minimalism, Marcus Aurelius’ stoicism, and ASMR videos, but a look back at the housing development Bel Vista in Palm Springs reveals an architectural medicament.

In the middle of the 20th century, there was much thought published around the topic of modern design. Mary and Russel Wright’s “legendary guide to stylishly efficient decorating, entertaining and home maintenance” entitled “Guide to Easier Living” was one of the most influential books of the time, promising “1,000 ways to make housework faster, easier and more rewarding.”

Originally published in 1950, the book was re-released by publisher Gibbs Smith in 2003 “to reintroduce the Wrights’ time-tested and proven methods for maintaining an inviting and efficient home. From ways to make household chores as fast and painless as possible, to how to organize a room for maximum living space, the Wrights pioneered a new informal way of living for a newly suburban American public.

The Wrights’ ideas revolutionized American living and the way everyday people dealt with the unending job of keeping a home in order. These methods and ideas are just as relevant — if not more so — today as they were a half-century ago.”

Julie V. Iovine, writing in the New York Times in 2001, noted, “While other industrial designers like Raymond Loewy, Donald Deskey and Gilbert Rohde focused on corporate offices, Wright understood that the American middle class needed help at home. The Depression and World War II had erased the old domestic landscape. Servants were no longer affordable; formal parlors were impractical; private bedrooms de rigueur, even for children. Beneath the banner of ‘convenience,’ consumerism was on the rise. And Wright was at the ready. With the help of Mary, his wife, muse and in-house marketing maverick, he resolved to teach Americans how to modernize their homes, down to their compartmentalized sock drawers.”

Alexandra Lange reviewing the book reissue in the Times in 2010 gave a now-amusing example of the recommendations.

“The book includes a chart demonstrating the Wrights’ ‘family cafeteria setting’ for dinner required 36 dishes, rather than the conventional 82 — and this when home dishwashers were still relatively rare," he wrote. "One of the most liberating ideas… was the ‘New Hospitality:’ you could serve dinner as a buffet, even from the kitchen counter. Guests could fill their own plates and clear them. You could serve a stew in a single pot rather than the traditional meat, starch and vegetable. A buffet, they added, worked best with lightweight and sturdy ceramic plates made to be stacked.”

But the Wrights, known for their beautiful tableware designs, were intent on transforming actual architecture, not just interior implements and furnishings. “We look forward to the day when living room, dining room and kitchen will break through the walls that arbitrarily divide them, and become simply friendly areas of one large, gracious and beautiful room,” they wrote.

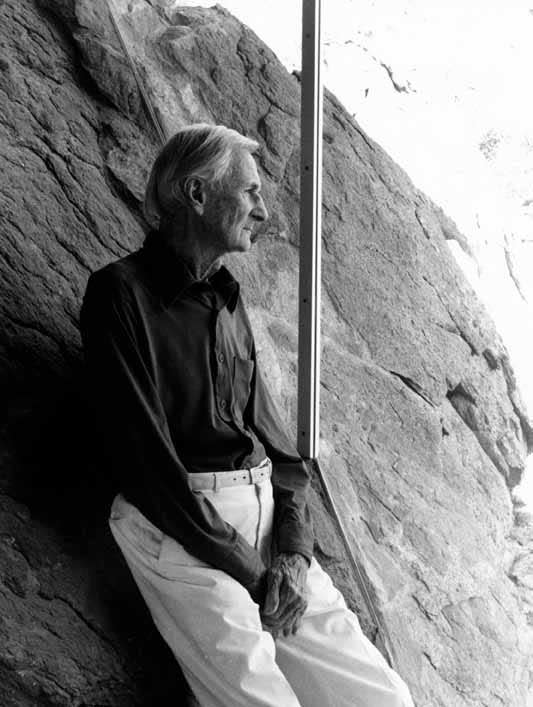

Architect Albert Frey was also thinking similarly. First writing in Architectural Record in 1931 with A. Lawrence Kocher in an article entitled “Real Estate Subdivisions for Low-Cost Housing,” Frey advocated for design solutions for small lots that would eliminate monotony of housing tracts, simplify floor plans and feel organic.

In his 1939 book “In Search of a Living Architecture,” Frey posits that “the natural environment influences the built environment” in a stunning statement not previously codified. By then, Frey was living in Palm Springs, and realized his theoretical musing for a small subdivision of 15 homes in his Bel Vista for developers Culver and Sallie Nichols.

Bel Vista, located on Calle Rolph between Tachevah and Paseo El Mirador, was originally planned as affordable workers’ housing and demonstrates Frey’s sophisticated design sensibility. Todd Hays, writing for the nomination to the National Register of Historic Places, observed, “Frey’s goal was to devise a plan that was both affordable and created distinct identities for each home at the street-front. The simple solution called for one single plan to be flipped, rotated, and placed with an altered setback from lot to lot. Different exterior finish colors were used to further differentiate the homes from one another.”

Inside, the homes featured a living and dining space adjacent to the kitchen, balanced by three bedrooms and a bathroom filling out the opposite side of a mostly simple square of a floor plan. Innovatively using outdoor lanai and covered carport to expand living space, the houses also had doors from the bedrooms and the dining area to the outside, instead of just a single front and back door. The yards included a service area for drying laundry enclosed in a curvilinear brick wall, which contrasted satisfactorily with the square shape of the rest of the little house.

One of the best-preserved of the tract is Bel Vista House #2 at 1520 E. Tachevah, which originally sold for $13,500 in 1946, presumably at a profit. (It recently sold in late July, 2023 for $895,000.) The house is sublime in its modesty, with Frey fully realizing the possibilities of simple desert living as a cure for modern existence.

In the decades after World War II, American homes slowly lost their separate, formal parlors and dining rooms. As servants disappeared, so did the separate kitchen; if mothers were doing the cooking, they needed a pass-through to keep an eye on the kids. If mothers were working, they needed wipeable mats, linoleum floors and a minimum of objects to dust and silver to polish. Convenience foods came into vogue, along with convenience materials and methods.”

Lange thinks that “the most fascinating part of the Wrights’ book is how thoroughly most of their ideas have been absorbed into our lives ... though, the slimming down of our domestic lives never quite reached its full potential. We might have cleaner lines and more convenient storage, but our furniture is bigger. Instead of one room in which to have a party, play games and watch TV, we have three. And the labor saved by single-pot meals, dishwashers and plastic mats hasn’t translated into more leisure time ... they told us how to simplify our lives, but we complicated them again.”

Frey’s Bel Vista illustrated a sophisticated understanding of those simplifying concepts and certainly comported with the Wright recommendations for easier living. Lange observed, “A 1955 advertisement for the ‘Guide’ read: ‘Let America’s Best-Known Designer Show You How to Have a Home That Almost Runs Itself!’ The Wrights were marketing more than just goods; they were among the first designers to sell a way of life.”

In Bel Vista, Frey realized the dream of a modern and modest house that practically ran itself and was the perfect recipe for happy living.

Tracy Conrad is president of the Palm Springs Historical Society. The Thanks for the Memories column appears Sundays in The Desert Sun. Write to her at pshstracy@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: Housing development Bel Vista’s recipe for a healthy and happy life