The Hotshots of Helltown

The canyon was burning. It was a dark night in early November, a new moon, and as the three friends looked out from the dusty rim of Butte Creek Canyon, in the foothills just outside Chico, California, they could see fires dotting the whole length of the landscape at their feet. Dharma LaRocca, Jeb Sisk, and Jason McCord had grown up down there, in a hippie community called Helltown that had once been a gold-mining camp. Now in their 40s, the men knew the territory better than anyplace else on earth. But as they watched the blaze curl like lava among the sycamores and hundred-year-old cottonwoods, they couldn't help imagining they were someplace faraway and exotic. Hawaii, maybe, or Mars.

The fires in the canyon represented the leading edge of a conflagration that had been burning since early that morning. Already it had consumed 20,000 acres, and it was now threatening homes in every direction. Taking backroads in Jason's truck, the three men had driven to the canyon rim, at the top of a rugged dirt track called Center Gap Road, after hearing a rumor that the 20 or so houses that composed Helltown were soon to go.

With the power out, the fires in the canyon offered the only illumination for miles, but the burning shrubs of manzanita and bottlebrush, and the booms of propane tanks exploding like distant artillery, helped the men orient themselves within the crumpled terrain. In front of them was the Steel Bridge, a local landmark not far from where Jason lived with his wife, Maria, who was also Dharma's sister, and their four children. But when they figured out where his house should be, they saw only a pall of black smoke. Repeating the exercise all along the creek, they looked for their parents' houses in Helltown, for the place in neighboring Centerville where Jeb lived with his daughter, and for the cemetery where Dharma had buried his wife after a car accident in 2012. From this vantage point, it looked like the canyon as they knew it had been obliterated. “It's gone,” they told one another, though they could each see very well for themselves. “All gone.”

While they watched the fires, the men saw a sudden slash of headlights in the smoke below. They wondered who could still be down there, so long after the fire department had come through waving evacuation orders. It was a truck, that much they could tell, bouncing back and forth in short sprints. Eventually, they realized what they were seeing—or, rather, who: It was their friend and neighbor, a 39-year-old off-duty firefighter I'll call Sam.

Sam, it turned out, had been in the canyon since midafternoon. Like the others, he'd grown up there, and he now lived just outside Helltown, in a house not far from his parents' and his uncle's. Earlier that day, Sam had been up north, three hours away, when he got a text from a friend that the canyon was being evacuated. Driving 90 miles an hour, he worked through a mental checklist the whole way home. Once back in the canyon, he went house to house, pulling furniture and propane tanks off porches to deprive the fire of ready fuel. Now that the flames were getting closer, he was racing in his truck to extinguish spot fires wherever he found them.

When the trio noticed the headlights, Jason called Sam on his phone. “Is that you down there?” he asked. “What are you doing?”

“I can't leave,” Sam told him. “I've got to protect my home.”

Dharma, Jason, and Jeb had come up to the top of Center Gap uncertain about what they'd find. At best, they figured, the rumor they'd heard would prove untrue, and they'd be able to slip back into the canyon to set free the horses and other animals their families left behind during their hasty evacuations. At worst, they'd at least be present to watch Helltown burn. None of them had expected to discover a close friend fighting an uncontrolled fire all alone.

From the top of Center Gap, Sam's efforts looked quixotic, possibly crazy. But seeing him down on the canyon floor made an otherwise impossible decision easy. “I think we can get down there,” Jason told Sam, studying the route that descended the canyon wall.

“Dude, are you sure?” Sam said. From where he stood, he could see the road, too. “I think it's on fire.”

When Jason nosed his truck over the rim, he and the others discovered that Sam wasn't wrong: Fires were burning on both sides of the road, all the way down. Near the Steel Bridge, the men found Sam cutting down a fence with a chain saw. The heat off the flames was palpable.

“Grab a shovel or grab something,” Sam told them. “I'm pretty glad to see you guys made it.”

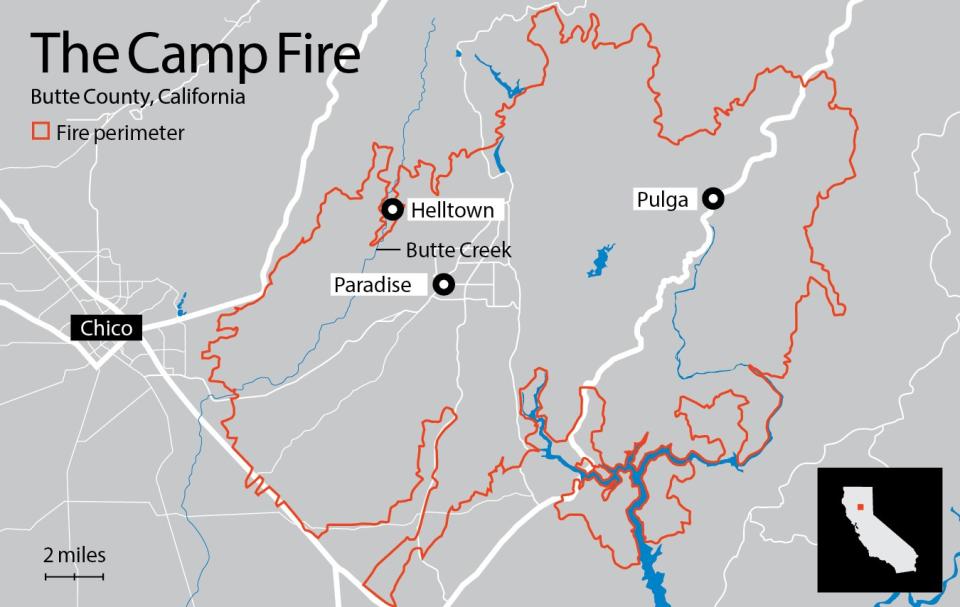

Dharma, Jeb, and Jason had no way of knowing it yet, but the fire they'd driven into would soon register as the deadliest and most destructive in California's history. Called the Camp Fire, after a road near its ignition point, the disaster made international headlines for the devastation it caused in Paradise, a densely forested town where hundred-foot pine trees were charred to blackened toothpicks and neighborhoods were reduced to piles of gray ash.

The Camp Fire would rage for 17 days, consuming an enormous swath of Butte County, a chunk of the state that shares little with the California of popular imagination. Though it's largely rural, and as securely uncoastal as Scranton, Pennsylvania, in many ways Butte County is pura California. Founded in 1850 as one of the state's 27 original counties, it was the direct product of the Gold Rush. About 50 miles north of Sacramento, Butte shares the same corner of the same Central Valley that Joan Didion once described as “a place in which a boom mentality and a sense of Chekhovian loss meet in uneasy suspension.”

By 2 a.m. the men were flagging. Their soles had melted, and their clothes were pocked with burns. They wondered how long they could hang on.

That suspension, however uneasy, held firm for the better part of 160 years. But this past fall, the Camp Fire introduced a new mode of loss, one whose literary prophet was less Chekhov than late-career Cormac McCarthy. By eight o'clock on the morning of November 8, only 90 minutes after its inauspicious start near a small artists' community called Pulga, the fire was roaring west, consuming a football field's worth of land every second. By nine, an apocalyptic firestorm was racing through Paradise, making its own weather and causing fist-sized embers—bits of burned books, utility bills, even plastic—to fall all over town. By noon, the smoke down in Chico was dense enough to perform an ad hoc eclipse, blotting the sun and dropping the ambient temperature several degrees.

Within about 24 hours, the fire would burn 70,000 acres, an area five times the size of Manhattan, and chase 50,000 people, almost a quarter of Butte County's population, from their homes. By the time the fire was fully contained, more than two weeks later, it had killed 85 people, burned 153,000 acres, and caused more than $16 billion in destruction, making it the world's most expensive natural disaster of 2018.

The smoke was visible from the canyon by 7:30 that first morning, a yellow-gray plume against the clear blue late-autumn sky. As it accumulated, the mass took on the shape of a thunderhead. Eventually it commandeered the entire eastern horizon, like a rogue sunrise.

Dharma, who worked at his family's organic winery and lived at the base of the canyon, 15 miles from Helltown, called his mom, Judy, when he heard about the fire on the news. She was untroubled. She and her husband had moved to the canyon in 1975, a time when the place was still populated by a contingent of epigone gold miners. Dharma's parents were back-to-the-land macrobiotic vegetarians who became enthralled with Butte Creek and the spirit of self-reliance that flourished there. They fell in with a tight community of hippies who played music together, swam naked in the creek together, and raised their children together. Dharma, Jeb, and Jason were all part of that brood.

When you'd lived in the canyon for as long as Dharma's parents had, you developed a sixth sense for fire. You knew how dry it could get in the summer, when the temperatures topped a hundred degrees, and you knew that the same narrow roads that buffered you from the sprawl of Chico also meant that any help from town would be a long time coming. You remembered the fires of the '80s and '90s that had swept through the canyon, when the Helltown hippies had traded 12-hour shifts on fire watch. But you also recalled that all those fires had blown in from the west. None had come from Paradise, up over the ridge in the east.

The Camp Fire, however, was different. When Dharma got word that the flames were nearing the canyon, he jumped into his truck to go persuade his mother to leave. He soon hit a roadblock and was told that an evacuation order was in effect. Dharma had to call his mother three times before she picked up.

“Get the animals, and get in your car, and get the hell out of there,” he told her.

“It's Pulga,” she insisted. “I'm listening to the radio now.” Pulga was 11 miles away.

“No, it's creeping over your hill,” Dharma said. “It's near the canyon.” Finally, his mom emptied her safe, packed a suitcase, and left.

In Paradise, the fire was a surprise that everyone was expecting. The town had grown up under a dense overstory of ponderosa pines and black-oak trees. According to one legend, it was this forest that earned Paradise its name, after a white settler found relief from the valley's heat in the cool of the trees. (Another story credits a miners' saloon called the Pair-o'-Dice.) Over time, the place became a shaded refuge for retirees, a quiet town of 27,000 where a Social Security check stretched further than it did down the hill in Chico.

The forest made Paradise, but many thought the forest would also be its undoing. The town was a paradigmatic example of the so-called wildland-urban interface, where houses and vegetation exist in a proximity that makes fires easy to start, quick to spread, and difficult to fight. For decades, firefighters in the area had predicted that a major fire would come to Paradise soon, and given how few roads led out of town, they worried it would be disastrous. “The threat to life is exacerbated by the large numbers of elderly and disabled persons, including a hospital and care facilities,” a report produced by a local nonprofit noted in 1998. “Many people will have considerable difficulty evacuating in the event of a major fire.”

Twenty years later, high winds, six months without significant rain, and the vegetation-drying effects of climate change brought those predictions to tragic reality. On November 8, at around 6:15 in the morning, PG&E, the local electric utility, registered an involuntary outage from a transmission line near Pulga. Fifteen minutes later, an employee in the area spotted a fire next to the tower that had been supporting the line. Cal Fire, the state's Department of Forestry and Fire Protection, has not yet definitively established that a spark from the utility line started the Camp Fire, but earlier this year PG&E acknowledged to its investors that its equipment was likely to blame.

Outside the canyon, the fire was causing whole towns to take flight. Anastasia Kontaxaki, a surgical nurse at the main hospital in Paradise, had already begun her first procedure of the day when the first spot fires arrived that morning. Just after 7:30, a colleague entered the operating room and announced that the building was being evacuated. It took a half hour more to finish the surgery.

Still in her scrubs, Kontaxaki joined a crush of nurses and nursing students wheeling patients in beds and wheelchairs to the emergency department to be evacuated by ambulance. Once the last patient was gone, she went to the parking lot to find her car. The smoke outside was dense, the sky was pink, and the wind was whirling ash like snow in a blizzard. Intending to drive down to Chico, Kontaxaki quickly found herself locked in traffic.

Already the fire was so big and so fast that there was no question of trying to put it out. The first responders in Paradise had two main priorities. One was to keep the roads headed out of town open as long as possible. The other was to set up temporary refuge areas to protect people who couldn't escape. Neither task was a given, and a car was not necessarily a safe place to be. The first five confirmed fatalities from the fire, and several more thereafter, were people who died in or near their vehicles while fleeing the flames.

Kontaxaki was nearly one of them. After sitting without moving for ten minutes, she was overwhelmed by the instinct to run. Though Kontaxaki had bad phone reception, she managed to send a text to her husband. She told him she loved him, and figured it would be the last he'd ever hear from her. Then she pulled her surgical mask and goggles onto her face and set out on foot.

It didn't take long for Kontaxaki to realize her mistake. Despite her mask and goggles, the smoke and the heat caused her eyes and nose to water and run. Fortunately, a man driving a minivan asked if she needed a ride. He was evacuating his wheelchair-bound sister, along with three older women. Kontaxaki climbed inside.

She wondered if she'd made another mistake when she saw the fire jump across the road in front of the minivan. The driver turned the car around and drove back through the massive ponderosas burning on both sides of the road. Eventually, after a few more near misses, they made their way downhill. The sky turned from black to bright blue. When Kontaxaki got phone service again, she called her husband, who was near Chico. She asked the driver to take her to him. The traffic there was stop-and-go, so Kontaxaki got out and walked among the cars until she found him. He gave her a hug, and she broke down crying.

Kontaxaki e-mailed the teachers at her kids' school, in Chico, and said she was coming to pick them up. Her fourth-grade daughter hadn't heard anything about the fire. “Why are you wearing work clothes?” she asked when her mother showed up in her classroom. “Why do you smell like smoke?”

How far is it from heaven to hell? In his Theogony, the Greek poet Hesiod said a bronze anvil would need nine nights and ten days to fall from the heavens to earth, and just as long to fall from the earth's surface to Tartarus, the home of the damned. Other authors would have other ideas—Milton pegged it at three times the radius of the universe—but according to the all-knowing Internet, the straight-line distance between Paradise and Helltown is just under three miles.

Around five o'clock that first evening, while Sam was frantically clearing combustible fuel from around his family's houses in the canyon, he saw the fire tip over the ridge from Paradise. Fire does not usually move fast downhill, but the winds propelled it into the canyon with terrifying speed. It was, he'd say later, “like a dragon was barfing fire. It threw up all over the hill.”

By the time Dharma, Jason, and Jeb caught up with Sam below the Steel Bridge that night, the winds had eased. The newcomers were relieved to see that the situation on the canyon floor was not as dire as it appeared from the ridge. North of them, a sliver of land that included Helltown, Jason's house, and much of Centerville was still unscathed.

None of the three men had come prepared for the task they were about to undertake. Jason, who co-owns a fertilizer company, was wearing a blue North Face jacket and sneakers. Dharma and Jeb, a finish carpenter, were in hoodies and jeans. Sam, in Carhartts, hiking boots, and a ski cap, gave them an impromptu lesson in firefighting. Wildland fires move by spotting, throwing embers ahead of themselves that blossom into flames. Left unchecked, those spot fires spread until they connect back with the main body of the blaze, effectively pulling the whole mass forward. But the time spot fires would need to ignite gave the men a crucial opening. If they could stamp out the embers—or, failing that, scrape a circle of bare earth to isolate them—they might be able to check the fire's advance.

Sam told his friends to keep their backup plans at the front of their minds. They should always know where the fire was, where the wind was blowing, and which direction they'd need to run to keep themselves safe. Jason should keep his truck away from power lines and pointed downhill. If things got bad, the men could huddle under the span of the Steel Bridge till the danger passed. If things got really bad, they could jump in the creek.

With the most immediate threat coming from the east, Sam said, they needed to hold the line at Centerville Road, the nearest approximation to a natural firebreak he could find. Keeping the fire on the far side of the road would give them a fighting chance to keep it out of Helltown until the professionals showed up. Given the disaster in Paradise, and the fire's approach to Chico proper, when that might be was anyone's guess.

Once the men got their instructions, Jason went to his house and drove back the tracked excavator he used on his property. Dharma and Jeb grabbed shovels from the truck and started working up and down Centerville Road. The job was hard but not complicated, and it kept them focused all night. While Jason used the excavator to dig lines around vulnerable buildings, Dharma, Jeb, and Sam kicked down fences, scratched firebreaks, and threw dirt on burning embers. They used their shovels and boots, even a kayak paddle, to knock down small spot fires. Around one in the morning, Sam warned the others that the fire was closing in on the old Centerville School, a squat yellow wooden building that was built in 1894. The schoolhouse was the nearest thing to a community center the area possessed. Bands played there in the summer, Santa visited in December, and potlucks were held year-round.

As the flames poured down the ridge, threatening to envelop the schoolhouse, Jason brought the excavator around. He started cutting a line with his scraper blade. “Watch my back,” he told Dharma.

“Dude, it's all around you,” Dharma said.

“I got it, I got it,” Jason assured him.

The fire hit the line just as Jason finished scraping. He pulled the excavator away in time, but not before one of its tracks popped off the wheels. As the excavator limped around the corner of the schoolhouse, Dharma watched the abandoned track light up and disappear in a puff of black smoke. Like a breakwater, Jason's line stopped the fire from advancing any further. The schoolhouse was saved.

By two, the men were flagging. The soles of their boots had melted from stamping out fires, and their clothes were pocked with burn marks from embers. They had no water; the only liquids they had on hand were two half-bottles of wine from Dharma's family vineyard and a few kombuchas.

For six hours the men had held the line at Centerville Road, and for six hours the fire had showed no signs of abating. But just as they were wondering how long they could hang on, the winds started blowing in their favor. All night Dharma had been thinking of his wife, Kelly, who was buried in the Centerville Cemetery near a friend named Callie, who had died of a stroke at 27. “Callie and Kelly gave us a little love,” he told the other guys. “They're looking out for us.”

Down in Chico, the family members of the four men knew none of this. A cell tower at the top of Center Gap had burned, leaving the canyon without service. At a friend's house, where several Helltown refugees had gathered, Dharma's sister, Maria—Jason's wife—tried to calm everyone down. The men knew the terrain in the canyon better than most people, she reminded the others. They were all strong swimmers, and they knew several abandoned mining caves where they could shelter in an emergency. Still, there was considerable concern. Dharma's girlfriend and 15-year-old son were on the verge of panic for much of the night, and his father was so worried that he didn't sleep.

Early the next morning, November 9, Dharma caught a signal from a distant cell tower and was able to get word to his girlfriend. “We need help,” he said. “We've got a lot of homes up here. We're not burned out yet. Call somebody.”

Maria arranged for a Cal Fire bulldozer contractor who also lived in the canyon to take Nyema Jankuska, a friend and neighbor, as well as a few other men, up to the canyon. The contractor, whom I'll call David—like Sam, he couldn't be sure that his bosses would appreciate his freelancing—had been working another part of the fire. As soon as he found someone to take his place, he jumped in his truck and picked up Nyema, who'd brought burritos and water for the guys in Helltown. His credentials got David waved through the roadblock at the base of the canyon that had stymied Dharma the day before. As David and Nyema approached Centerville Road, swerving around downed power lines and toppled utility poles, they saw that the Honey Run Covered Bridge, a Chico landmark that was built in 1886, had burned to the ground.

After checking several houses, David and Nyema found Dharma, Jason, and Jeb on Centerville Road, just below the cemetery. It ought to have been a congenial reunion, but in those first minutes, the three men, delirious with exhaustion, thought David and Nyema were looters. Shovels in hand, their faces streaked with charcoal, they started chasing them, yelling, “Get the fuck out of here!”

As the professionals arrived, they were perplexed by the sight of civilians working the fire with shovels, a chain saw, and an excavator. “We held the line,” Dharma told them.

The confusion didn't last long. David brought a dozer back up Centerville Road and started digging lines. Nyema went to his mom's house to cut trees, clear brush, and blow leaves.

The professional firefighters showed up around noon. Expecting to see the same scorched wasteland the fire had left behind everywhere else, they were stunned to find a cluster of houses still standing. Even more perplexing was the sight of civilians working the fire with shovels, a chain saw, and an excavator. “We held the line,” Dharma told them. “There are a lot of houses up here still untouched.”

By four o'clock that afternoon, the canyon was swarming with firefighters, engines, even a helicopter. Sam briefed the new arrivals, explaining how and where the fire had been moving and showing them where Jason and David had cut defensive lines. He pointed them to a house above the cemetery that was at risk of burning and was gratified to see an engine company arrive in time to save it.

I first heard about what was happening in Helltown while the fight to save it was still under way. Like Dharma and the others, I grew up just outside Chico, albeit on the opposite side of town. Sam and I were on the ski team together at Chico High, and Nyema and I played together in a very amateur rock band. Jason's wife, Maria, was a close friend of my next-door neighbor's, and Jeb's sister was a few years ahead of me in school.

If I wanted to be neat about it, I could say that the Helltown guys were raised among the hippies while I grew up among the farmers, though the truth is that those distinctions had long since eroded. Still, there were differences in tone. In the canyon, they had jam bands that played together for decades, sweat lodges on the creek, and organic food and midwives quite long before organic food and midwives were everywhere. Down in the valley, we had almond and walnut orchards, boot-cut Wranglers and silver belt buckles, and the 4-H auction each spring, where we brushed our hogs with baby oil and balled the tails of our Charolais steers with hair spray. Between us, both literally and metaphorically, lay Chico proper, which for decades had depended on the farmers to stay prosperous and the hippies to stay interesting.

The first night of the fire, I was home in Brooklyn, where I now live. I got a text from one of my closest friends, Joriah Dering, who lives in Helltown with his toddler and his fiancée, Nyema's sister. “Our part of the canyon is starting to burn above the schoolhouse/museum,” he wrote. “Fuck me.” Online maps that made use of satellite and aerial infra-red data allowed me to follow the fire's progress from across the country, nearly in real time. With Joriah's house on my mind, I couldn't help but notice a jagged finger of unburnt territory, shaped like the hinged barb of a harpoon, that dropped down from the north and came to a point below the Steel Bridge.

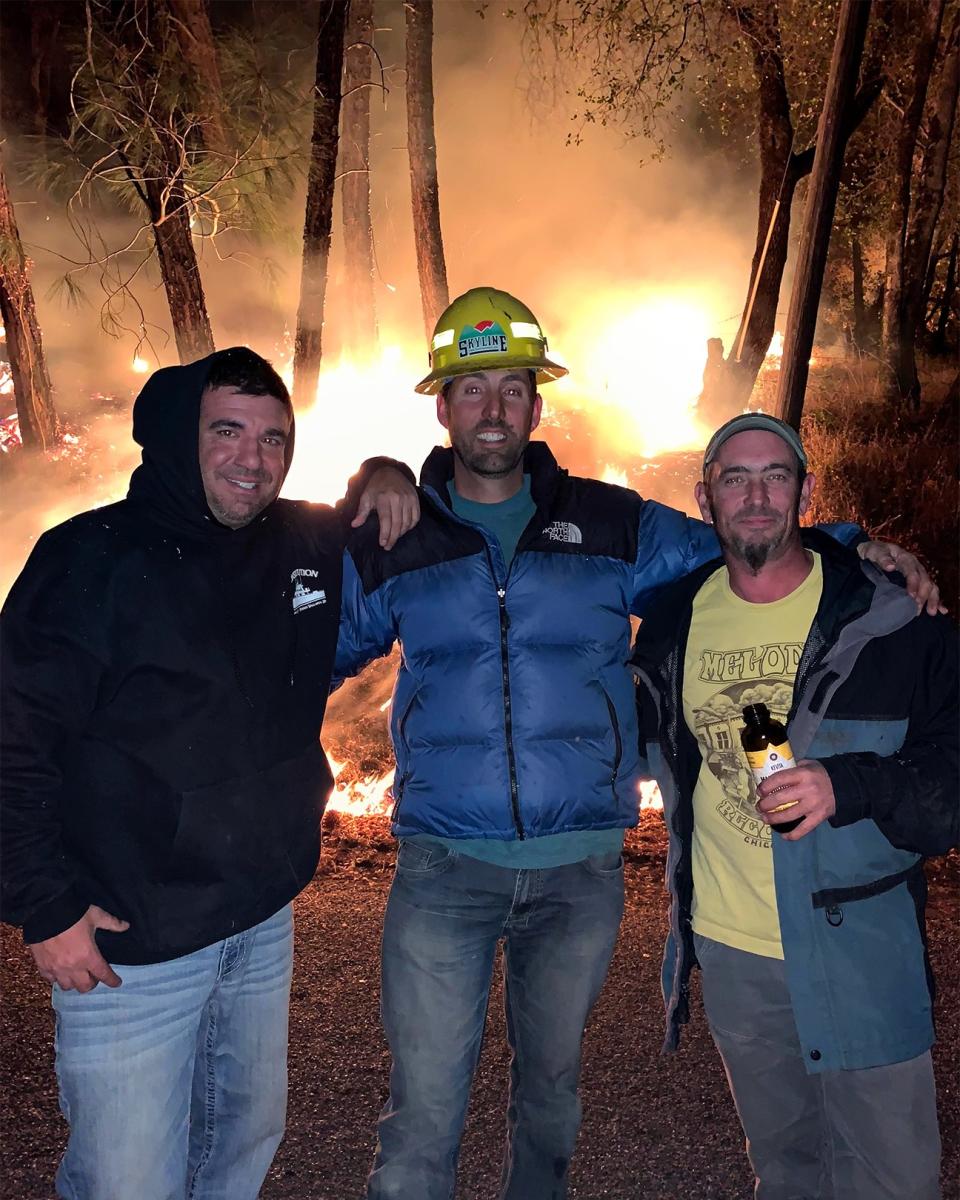

Two days later, Joriah wrote again: “Just got word. Our buddies…are up there with bulldozers cutting fire lines. They've been up all night fighting spot fires, saving houses. Helltown hasn't burned yet. Gotta get through the wind event tonight. 🙏🙏🙏🙏” He sent a picture of Dharma and Jason and Jeb. All three were flushed but smiling.

On Friday afternoon, soon after the professional firefighters arrived, Dharma and Jeb caught a ride back to Chico. Sam, Jason, and Nyema stayed behind to look after their families' houses. Jason offered his property as a staging area for the firefighters. He made signs to show where the engines could pump water from the creek.

All Friday night and into Saturday, the third day of the fire, the firefighters were able to check the flames' advance in part by back-burning: literally fighting fire with fire. By Saturday, when I got Joriah's second text, it looked like Helltown would make it through. Sam lay down at his house—the first sleep he'd gotten in two days. Jason found a bottle of champagne at his place and popped the cork.

Around eight o'clock that night, however, David and Jason heard some bad news: Fueled by gusting winds, the fire had blasted into the northern end of Helltown, where it destroyed two houses and burned so ferociously that the firefighters had to pull out of the area to stay alive.

In that instant, it seemed as though much of their efforts were for naught. Jason called Maria. “Helltown's gone,” he said.

Shortly after midnight, Sam awoke and saw the glow over Helltown out his bedroom window. “Oh, hell no,” he said to himself. He drove up to talk to the dozer operators who'd been working the blaze. Recognizing that the winds were changing course yet again, he concocted a plan. He told the men on the dozers that if they were able to choke the fire where it had entered Helltown, it would have nowhere to go. “We cut this thing off, this fucking fire's done,” he said.

The bulldozer crew cut a broad line at the spot Sam had in mind. Once again he was right: The fire, at least in the upper canyon, was finished.

In the days and weeks after the fire, media from all over the world descended on Butte County. For anyone who grew up in the area, it was an unsettling spectacle, for reasons that had nothing to do with modesty. If anything, in fact, our problem was a surfeit of self-satisfaction, a super-abundance of conceit. Possessed of more native pride than we know what to do with, we Chicoans tend to lionize anything that has even a glancing association with our hometown: Sierra Nevada, the Chico brewery that helped launch the craft-beer industry; Aaron Rodgers, the Packers quarterback who played for a local high school; Raymond Carver, who took writing classes at Chico State. But we also know that for a town like Chico to claim a dateline in national newspapers for several days running is, as my physician wife likes to say, a poor prognostic indicator. It's not the sort of place that makes international news when things are going well.

Now, all of a sudden, things were bad enough that even America's homebody president felt obliged to come. Standing among the glossy black trunks of the scorched ponderosas in Paradise, Donald Trump spoke about the devastation. “Hopefully this is going to be the last of these, because this was a really, really bad one,” he said. “I think people have to see this, really, to understand it.”

Paradise is Trump country, and plenty of people were happy to have him visit. But the president did himself few favors with his local fans when he blamed the fire, essentially, on the people who had suffered from it. (Trump claimed that the president of Finland had told him Finns don't have trouble with forest fires because they “spend a lot of time on raking and cleaning and doing things.” The Finnish president later said he told Trump nothing of the sort.) Later that day, Trump compounded the insult by twice referring to Paradise as “Pleasure.”

Nine days after Trump's visit, the day after the authorities announced that the Camp Fire had been fully contained, I returned to Chico and found it in the grip of a deep, nearly tectonic re-orientation. The town had been the obvious destination for most of the fire's evacuees, because of both its proximity and its size. At just over 90,000 people, it was the largest town in an 80-mile radius. Almost literally overnight, its population swelled by nearly a third.

The influx of evacuees meant that the tragedy that had started in Paradise had now come to Chico. RVs and fifth-wheels showed up on city streets all over town. (“If you see it, there's somebody living in it,” one evacuee assured me.) Hotel rooms, Airbnbs, and apartment rentals disappeared from the market, and Chico briefly became, in the unthinking argot of the National Association of Realtors, the “hottest” real-estate market in the country. Restaurants offered free meals to evacuees and first responders, fund-raisers and clothing drives were ubiquitous, and a former Sears at the Chico mall was reconfigured as a FEMA disaster-recovery center.

Other relief efforts were ad hoc, impromptu, invisible to all except to those on the receiving end of them. Houses opened to friends, friends of friends, and even strangers. Donations filtered into Venmo accounts that paid for gift cards pressed into the hands of people still too proud to think of themselves as charity cases. Companies paid their affected employees to come to work and cry with their colleagues, or not to come to work at all. At least one person I know moved out of his apartment to make room for a displaced family.

When conversation turned to Paradise, the talk got melancholy, at times almost despairing. I met several former residents who insisted they would move back as soon as the toxic soil was removed and the charred trees were felled and the incinerated houses were rebuilt. But even they were aware that the choice might not be theirs to make. People need more than houses to live: They need friends to visit, places to work, stores to shop for their milk and beer and Scotch tape. By the time Paradise High School held its first day of classes after the fire—online and in a vacant store at the Chico mall—some 350 students, more than a third of the total before the fire, had enrolled elsewhere. Even the most optimistic estimates predict it will be years before anything like an independent Paradise returns.

Against that backdrop, the rescue of Helltown stood as a small, happy story that no one was too stoic to admit needing to hear. Somewhat to my surprise, Sam was not the only firefighter I spoke to in Chico who said that he, too, would stay behind to fight a fire threatening his home. “There's a saying,” a city firefighter told me. “If you can keep the first house from burning, none of the houses will burn down. Because the house that catches on fire, that puts off the big embers and catches the other houses on fire.”

The authorities, of course, do not recommend this course of action, especially for civilians. Scott McLean, a Cal Fire spokesman who raised his family in Chico, says he understands the temptation to try to save one's home. Nevertheless, he said, “I don't condone it. I mean, 86 people died.” (The death toll has since been revised downward.) “I'm surprised they didn't die in Helltown. I understand the reasoning, but it's stupid.”

“I don't know if you want to call us stupid dumb-asses,” Dharma told me. “That was four dumb-asses not wanting their families to burn out.” Still, he and the others were keenly aware that they had a lot of luck on their side: At several crucial points, the wind might not have shifted to help them. Mostly they feel grateful that they had Sam guiding their efforts. “He's got the mind of a firefighter,” Dharma said. “He would be like, ‘I think this place is under control,’ and I was like, ‘Really? There's a 40-foot flame there.’ He was like, ‘Yeah, but it's burning out of fuel and the bottom's all done. It'll be fine.’ ” When they'd come back, later in the night, the fire would be out. “He'd be like, ‘Yep, I knew it.’ ”

Not everyone who stayed behind had the same good fortune. Gordon Dise and his 25-year-old daughter, Anna, also lived in Butte Creek Canyon, on a two-acre property a few miles downstream from Helltown. After watching news about the fire until the power went out, Gordon asked Anna to help him rig up a fire hose to their large water tank, which they used to spray down the vegetation around their house.

That night, after eating dinner in the dark, Gordon and Anna saw flames as tall as trees approaching their property. They rushed to pack a box of paperwork, a bag of family photos, and an assortment of clothes. By the time they'd finished, the fire had reached the deck of their house. The blaze was as loud as a waterfall and hot enough to chap their faces like a sunburn. They put their belongings in their car, along with their two dogs, and were about to leave when Gordon ran back to the house.

Anna yelled after him, and when she realized that he couldn't hear her over the roar of the fire, she honked the car's horn. There was no sign of her dad. When she saw her kitchen collapse, she started the car and tried to drive away from the burning house. Only then did she realize then that the tires had melted.

Anna took the dogs down to a ditch that connected her neighbor's duck pond to Butte Creek. She soaked her clothes and hair, and watched her house burn. Temperatures that night were in the 40s, and though she knew it was insane, she was tempted several times to go back to the fire to warm herself. At one point, one of her dogs ran off and didn't return. The other remained with Anna, watching for wild animals.

Though cell service was spotty, Anna eventually got through to 911. They told her they'd send someone to get her, but no one came. Worried that the wind might shift, she kept herself awake all night, watching for hot spots and dousing her clothes whenever they got too dry. The fire at her house burned through the night and spread down to the trailer park across the street.

At dawn the next morning, Anna drank some water from the duck pond before walking over to her house to see if she could find her father. She found her missing dog, alive, but there was no sign of Gordon's body. The heavy burr of chain saws on the main road led her down to a clutch of firefighters who were plainly shocked to see her. They fed her and her dogs before driving them out of the canyon. Twenty-four days later, her father was officially confirmed as a fatality of the Camp Fire. Anna still doesn't know why he went back to the house.

On a cold sunny day in late November, I met with Dharma, Jeb, Sam, Nyema, and Joriah in a parking lot just outside the canyon. Jeb's parents were there, too, as was Nyema's mom. Though it had been more than two weeks since the fire was extinguished in their part of the canyon, the evacuation orders were still in place. A few neighbors had been allowed back to feed their animals, but everyone else was getting antsy.

On the way into the canyon, I rode in Sam's car with Dharma and Jeb. In the lower canyon, the fire had been hasty and capricious, leaving some areas unharmed and burning others completely. All along Centerville Road we saw scorched houses, twisted knots of sheet metal, and trees that had cracked down the middle, as though struck by lightning. “It looks like an atom bomb,” Dharma said when we crossed through one particularly bleak area.

We passed a stone house that the flames had rendered a blackened pile of rubble. Sam recalled seeing the owner during the first night of the fire. “He was just sitting there, and he's like, ‘Man, all I'm gonna do is just watch the fire now.’ His house had already burned down. He was like, ‘Yeah, I said goodbye to it, and I'm just gonna watch it.’ I think he went to bed for a while under the bridge. It was trippy.”

At the Steel Bridge our small convoy was stopped by a baby-faced National Guardsman in a Humvee. He said that he couldn't let anyone through, which made the Helltown crowd furious. “I saved my home from burning,” Jeb told the guardsman, “and now I can't get into my own home.”

Before long, a few sheriffs and highway patrolmen arrived. “I know you're frustrated,” one of the patrolmen said. “The bottom line is that until the body count gets recovered, they're not opening these things up. I'm going to tell you frankly, they're not concerned about you guys being out of your house. They are preoccupied right now with 700 dead bodies.”

It was understandable, even if we would soon learn that there were nowhere near 700 bodies to be found, but also aggravating. The evacuees had been out of their homes for nearly three weeks. They wanted to go home.

Finally, a few days later, the Steel Bridge opened again. Not long after the evacuation orders were lifted, a placard was affixed to the street sign at the base of Helltown Road:

Thank you: All firefighters & emergency personnel

Butte Creek Canyon Volunteer Fire Co.

Our secret weapon: the Helltown Hotshots

Robert P. Baird has written for the ‘London Review of Books’ and ‘Harper's Magazine.’ This is his first article for GQ.

A version of this story originally appeared in the May 2019 issue with the title "The Hotshots of Helltown."