We Can Honor Representative John Lewis By Doing Much More Than Renaming a Bridge

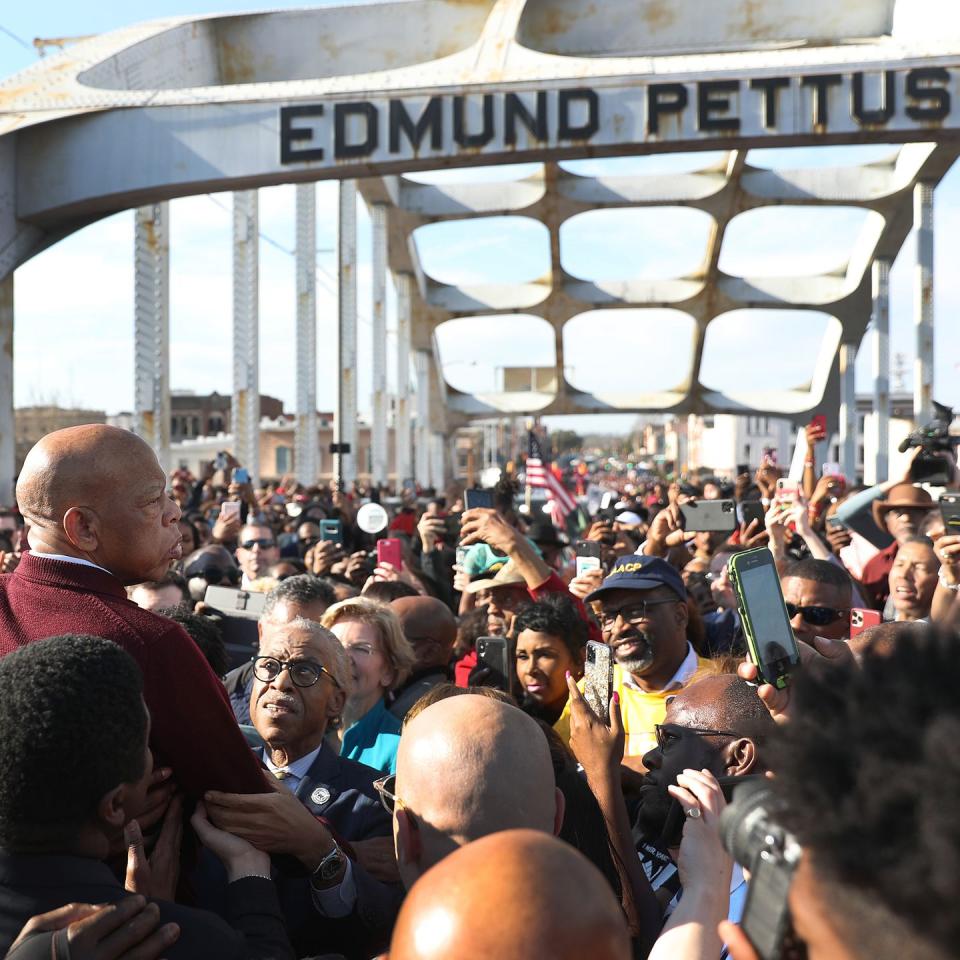

“I remember the day started out cold,” Representative John Lewis told me of the day he set out to march across Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge in 1965. “Cold enough to see our breath as we walked.”

It was March 7, 2015, and I was standing with Representative John Lewis just outside the Brown Chapel AME Church in Selma, Alabama. Fifty years earlier, a young Lewis, then chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), had knelt in prayer with some 600 courageous black folk before embarking on that fateful march. I'd asked him what he remembered.

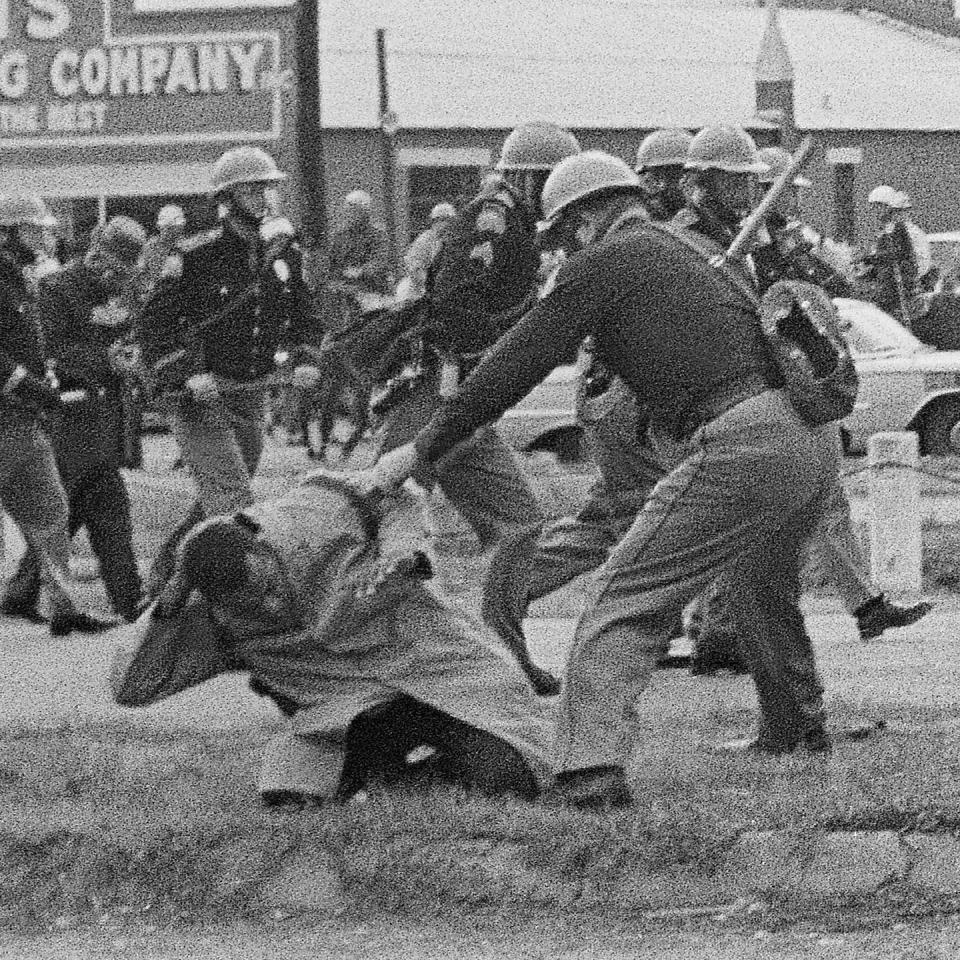

I was accustomed to engaging guests with lighthearted banter during commercials while filming my cable news show, but nothing about standing next to John Lewis in Selma felt lighthearted. Fifty years earlier, a young Lewis, then chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) suffered a fractured skull when he was brutally beaten by one of the 150 Alabama state troopers who attacked the peaceful voting rights demonstrators with clubs, bullwhips, and tear gas.

I’ve seen the historic image many times—Lewis’ on his knees, his right hand covering the first wound to his head, the state trooper holding the collar of Lewis’ trench coat, club raised to strike another blow. I never wondered why he was wearing a long coat on a spring morning in Alabama. Now I knew: Lewis was cold. It was an important reminder that for him, Bloody Sunday was not a metaphor or symbol. It was lived experience, as stark and real as the brutality enacted on his body.

Edmund Pettus was a Confederate Army officer and leader of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan. In the wake of Representative Lewis’s passing, there is renewed energy to strip the iconic bridge of its racist homage, and rename it for Congressman Lewis.

I don’t care about statues or memorials. As a Southerner, raised amid pervasive Confederate iconography, I am not overly concerned with what chunk of concrete or metal will be raised or renamed to honor the late Congressman John Lewis.

He was human, not granite. He felt cold and pain. There is only one monument that can begin to acknowledge the sacrifices and successes of this most courageous legislator of our age: restoration of voting rights by immediate passage of the For the People Act.

Four years after Representative Lewis commemorated the 50th anniversary of his own bloody sacrifice in Selma, Alabama, he presided over the House of Representatives as it passed HR1: For the People Act of 2019. The bill restores key protections of the Voting Rights Act, which was gutted six years earlier by the Supreme Court’s 5-4 decision in Shelby County v. Holder (2013).

Shelby invalidated Section 4b, the criteria in the 1965 Voting Rights Act used to determine which states and localities were required to seek federal approval (also known as preclearance) before making changes to their voting processes. Without preclearance requirements, states were free to enact aggressive measures reducing access to the polls and they did so with breakneck speed and efficiency following the Court’s decision. According to the Brennan Center for Justice the Shelby County decision “unleashed a wave of voter suppression efforts” including voter ID requirements, voter purges, reduction and elimination of polling places, and restriction of early voting days. The long lines, broken voting machines, and voter purges that marred the state elections of Lewis’ own state of Georgia in 2018 and again this year are a disgusting and disturbing inversion of his legacy.

The provisions in HR 1: For the People have the power to breathe life into our mortally wounded democracy. The bill includes provisions to modernize and protect voting systems and to once again require federal preclearance for states with a long history of voter suppression. After successfully passing the House of Representatives the bill arrived in the Senate, where it has been sitting on the desk of Senate Majority leader Mitch McConnell for more than 225 days.

Our ravaged electoral system in the midst of a deadly, global pandemic, means that voting in 2020 is terrifying, potentially even life threatening. John Lewis was intimately familiar with risking your life to vote.

Lewis told me he was not afraid when he faced Alabama state troopers in 1965. “In that moment I was keenly aware that I was prepared to die for what I believed in.” He never wavered—through passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, to leadership of the Voter Education Project of the 1970s, to advocacy of the the periodic reauthorizations of the VRA, to witnessing the Supreme Court “stab the Voting Rights Act in the heart,” to his return to Selma even as he battled stage 4 cancer. His courage is unparalleled.

I have known great men who become smaller as you get closer to them—tall, bright, big-voiced and with fancy titles from afar, but up close their selfishness, unkindness, brutishness, or sexism comes into focus. John Lewis was the opposite. Soft-spoken and diminutive, he could grow to the stature of a titan before your eyes. Universally beloved by his Congressional staff and unreservedly admired by his colleagues, Lewis was consistently and publicly supportive of younger activists making good trouble. He was stern with the powerful, and gentle with the powerless. He even occasionally tweeted about his cats and played with rescue puppies.

I learned something new and was newly inspired by every single encounter I had with him. I wept unreservedly when I learned of his passing. John Lewis was human, certainly imperfect, but likely better than most of us even aspire to be. He deserves roads, bridges, statues, and holidays, but he has earned much more than that—he has earned a living legacy for his life’s work. Lewis lived with an urgent determination to fulfill the promise of American democracy. We have the power to demand that Congress honor his legacy with immediate action to pass the For the People bill into law.

You Might Also Like