Home Is Where the Jamaican Beef Patties Are

If you visited the Jones family household anytime in the late ’80s or ’90s, you might have found a Jamaican beef patty shoved in between the sofa cushions. Or under someone’s pillow. Or tucked into a bookshelf. These are the measures that must be taken when one lives in a house with eight siblings, two grandparents, any number of visiting aunts and uncles, and a mother who can only roll out 24 of her famously flaky, juicy, meat-stuffed, turmeric-tinged patties at a time. (Which may sound like a lot, but do the math.)

“Look, I’m number seven of the siblings,” says Shani Jones. “When you’re one of the youngest, you have to either stick up for yourself—or hide your patties. So I hid mine under the couch.”

These days, Shani no longer needs to squirrel away her patties. Instead, she makes them herself, using an industrial grade Hobart mixer and a dough sheeter that can roll out 250 at a time. The recipe is the backbone of her catering company, Peaches Patties, named in honor of Shani’s mother, Victoria Jones, a.k.a Peaches.

But shortages still happen. Shani’s company is one of the only Jamaican food purveyors in San Francisco, and the beef patties are the most popular item on her menu.

The story of the Jones family patty recipe begins before Shani was even born. Her father, Martin, left his hometown of New Orleans at the end of the Great Migration, heading west to San Francisco. Her mother, Victoria, was a nursing student in Trenchtown, Jamaica. The two met through a penpal company. “It was like eHarmony or Match.com back in the day,” Shani says. “My mom had penpals in Senegal, in Cuba, all over. But she and my dad really clicked, so one day, he decided to come out and visit her in Jamaica.”

One trip was all it took. Six months later, Victoria had relocated to San Francisco. She married Martin and never looked back. But she brought her patty recipe with her, handed down from her own mother, and raised her eight children in a house suffused with Jamaican culture and cooking.

Jerk chicken, fried plantains, peas and rice, beef patties: These were the flavors of Shani’s childhood, but home felt like an island of sorts, in the middle of a city largely devoid of Caribbean community. “Even today, there’s not much of a Jamaican diaspora out here,” she says. “Most of it is on the East Coast.”

Growing up, Shani did her best to assimilate with an outside world that differed largely from her interior one. She got good grades, made friends, followed the rules. But it wasn’t easy; cultivating emotional barriers became a survival tactic. “Black people here are marginalized,” she says. “We are looked at and treated differently. In order to keep on functioning, you need a certain degree of numbness.”

It wasn’t until she moved across the country for college that Shani saw things could be different. Studying Mass Communications at the historically black Clark Atlanta University, she found a vastly different community, where black people held positions of power—professors, doctors, politicians—and Caribbean culture thrived. Even Atlanta’s grocery stores were better, with shelves upon shelves packed with jerk seasoning and Scotch bonnets and bottles of Pickapeppa sauce.

After graduation, Shani visited her mother’s home country for the first time. “As soon as I got off the plane in Kingston and went outside, I don’t know what it was, but it rushed over me,” she recalls. “I felt this calmness. Like, wow, okay, I’m home.” She ate patties at a local shop and visited her ancestral stomping grounds—the verdant Saint Elizabeth countryside where her grandmother grew up, her mother’s high school and community theatre and nursing academy in Trenchtown.

“Jamaica was an awakening moment for me,” she says. “I wasn’t numb anymore. I was grieving for the first time, that disconnection I grew up with. I never knew that I could actually feel that relaxed before.”

When she returned to San Francisco, Shani was determined to regain this sense of connection. “I came back and realized there was still no Jamaican food outside my mom’s house,” she recalls. So, while pursuing a PhD in Organizational Leadership and Management and driving for Lyft, she returned to her mother’s kitchen to recreate some of her family’s classic recipes—juicy jerk chicken thighs, veggies stewed in creamy coconut curry, and of course, the famous beef patties. But this time, they weren’t just for family. They were for friends, then strangers. Small events, then larger ones. As word spread, so did demand.

“I started having casual conversations while I was doing Lyft rides,” Shani says. People would ask her if she did rideshares full time. “No,” she’d tell them, opening up about her PhD, her fledgling business, her struggle to balance it all with a gig economy salary and San Francisco’s rapidly rising cost of living. “Within those conversations, three separate times, people asked me: Have you heard of La Cocina?”

She had not. But a bit of Googling led to a free orientation workshop, which led to an application, which led to an acceptance. And suddenly, Shani was a member of one of the country’s most successful nonprofit food incubators, an organization dedicated to helping Bay Area women, immigrants and people of color to open their own successful businesses.

Through La Cocina, Shani learned how to brand her business. She moved production out of her mother’s kitchen—a space she’d outgrown—and into La Cocina’s shared industrial kitchen space. There, a pastry chef taught her how to scale up the patty recipe, from batches of 24 to 250. And it was La Cocina that helped Shani find a retail space: a kiosk at 331 Cortland Marketplace in Bernal Heights, sidled up against other food sellers from all over the world, many of them fellow graduates of La Cocina.

“With La Cocina, I’ve been able to get more help than I would’ve on my own as far as navigating this industry,” says Shani. “Just having a space to start and grow my business, and people versed in the field who could meet me where I needed them the most—that’s what helped me grow and flourish.”

On December 23, the Marketplace shut down due to rising rents—a problem that’s become devastatingly familiar to restaurateurs all over San Francisco. But Shani is undaunted. Business still booms, and she’ll keep running her catering business—alongside her nine-person staff—from La Cocina’s shared kitchen.

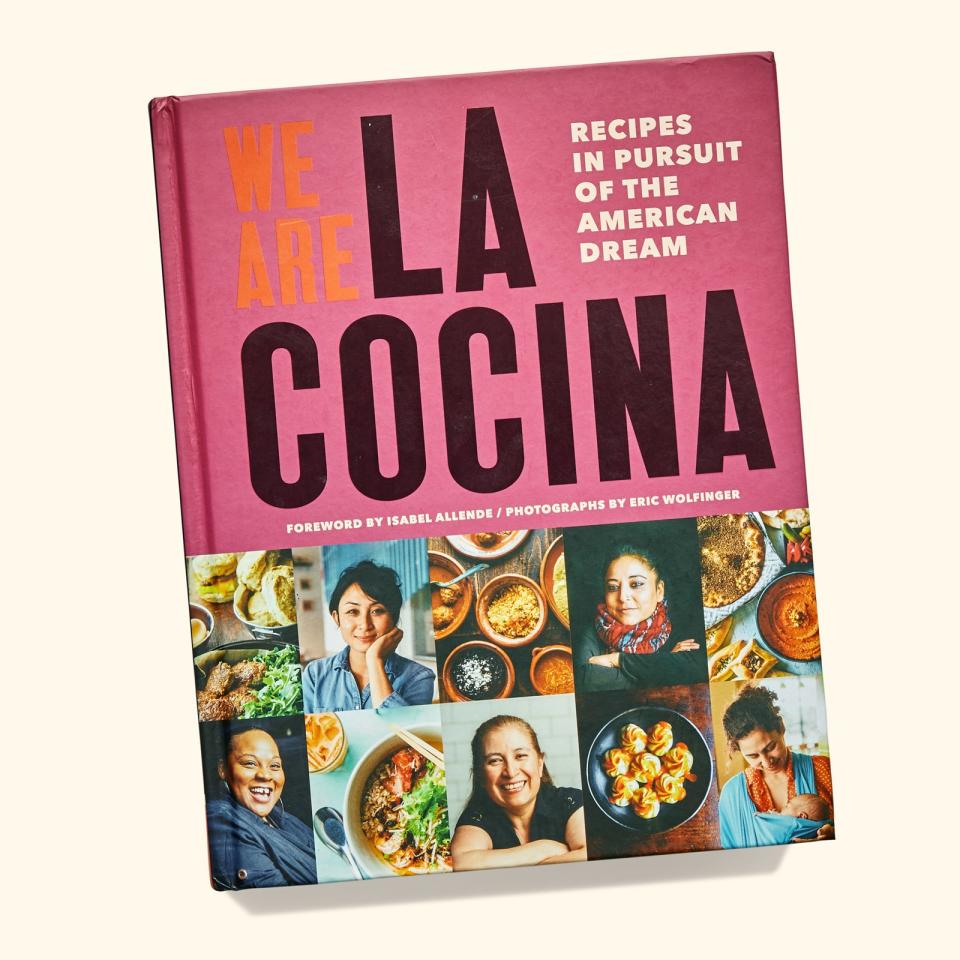

Meanwhile, her beef patty recipe, along with her family’s origin story and her jerk chicken, is now featured along with 80-something other recipes from fellow La Cocina grads in the organization’s beautiful new cookbook, We Are La Cocina. “In this book, I was able to actually tell my story, to show who I am, to share my rich heritage of being American but raised the Jamaican way,” says Shani. “All of the recipes in this book are tacit knowledge, written down on paper to make them explicit knowledge for everyone else.”

Eventually, La Cocina will help Shani and her staff find a new, larger, standalone restaurant space, where platters of oxtail curry and tangy escovitch snapper will share a menu with her husband’s misir wot, a spicy red lentil stew from his own home country of Ethiopia. It will be a nucleus of community, for anyone who needs it.

And occasionally Peaches herself will pop by—incognito, of course; she’s a celebrity now—to stock up on a few dozen of those famous beef patties.

Buy it: We Are La Cocina, $19 on Amazon

All products featured on bonappetit.com are independently selected by our editors. However, when you buy something through our retail links, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Get the recipe:

Jamaican Beef Patties

Originally Appeared on Bon Appétit