The Holy Mountain

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Only 20 hours after lockdown was declared in California, in March 2020, my mother was rushed into the hospital in an ambulance. She was losing blood, fast. The phone had rung in our little apartment in Western Japan, and the ambulance driver had asked me if I really wanted to send my 88-year-old loved one to the ICU. A hospital, in those early days of the pandemic, felt more dangerous than anywhere. As my mother’s only close living relative, I had to say yes, and then I secured a seat on the next flight back. Minutes later, a friend sent an email: No visitors were allowed in hospitals. I was as close to my mother in Japan as I would be up the road in Santa Barbara.

What could I do? I hastened across the park in my quiet neighborhood and down a flight of barely noticeable steps to the local Shinto shrine. I threw coins in a wooden box and clapped my hands to summon the gods. I prayed for them to protect my mother, and the whole uncertain world. Then, walking back through the bright spring sunshine, I began to think of Koyasan, the mystical mountain three hours away at whose top stand 117 Buddhist temples and 200,000 graves, guarded by centuries-old cedars.

I’d traveled to the holy mountain twice with the Dalai Lama, my friend for 48 years now. Amid the rusting maples and deep silences, I’d heard him remind us that “death is part of our life.” We prepare for job interviews, a driving test, even a first date. Might it not be useful to ready ourselves for the one non-negotiable fact of life?

All of us could feel death breathing down our necks during the pandemic. In Japan, however, the Dalai Lama’s invocation of the Buddha’s First Noble Truth—the reality of suffering—carries particular force. For 1,400 years or more, my adopted home of 35 years has been living with warfare and earthquakes and fires and tsunamis. Reality, my neighbors seem to know, is the only home we have. If we’re going to find paradise anywhere, it has to be right here.

I remembered my first trip to the templed mountain, 14 years before. I’d met a Swiss monk in a funky café along the hushed main street. “In Europe,” he’d told me, “people talk of mountains as ‘ladders to heaven.’ Here in Japan, people come to the mountains in order to die.” Or, perhaps, to find what never dies. Twice every day, I watched monks in robes carry fresh meals on an elegant stretcher of sorts to Kobo Daishi, the founder of the mountain’s Buddhist order, who stopped breathing in the year 835 but is believed to be sitting still in meditation here.

Most of us are in no hurry to think of the end of things. Yet as the English novelist E.M. Forster wrote, “Death destroys a man, but the idea of death saves him.” Not knowing how much time I—or anyone around me—had, during the pandemic, reminded me to reflect on what was really important. On what I loved most and how I could stay close to it. Living next to death moved me to think about how to live.

As I called the hospital every day—my low-tech mother and I even enjoyed our first FaceTime conversation, thanks to an enterprising nurse—I found a strange comfort in thinking about the mountain nearby. In Japan, the dead are believed to have moved only to another room, from which they still at times return to look in on their loved ones. My Japanese wife, Hiroko, seemed to be expressing a universal truth when she said that her parents somehow lived more fully in her after they were gone than when they were down the road.

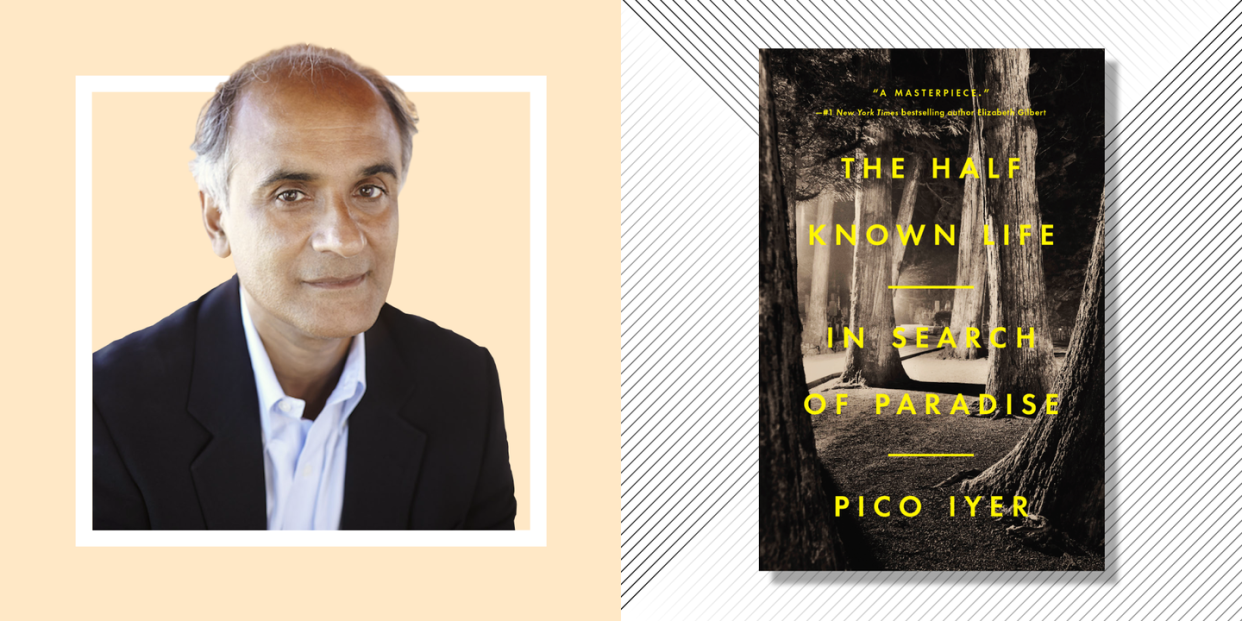

The Half Known Life: In Search of Paradise

amazon.com

amazon.comThus Koyasan became the center of my meditations as I waited to fly back to see my mother. And I embarked on a book about paradise, drawing on 46 years of constant travel to Jerusalem and Kashmir and inner Australia and Varanasi. Most of us long for a better world or self, but how can we ever find that in the midst of real life—and in the face of death? I traveled to Iran, whose culture long ago gave us the word pairidaēza. I visited the Shangri-La–worthy temples of Ladakh. But it was Koyasan that taught me most deeply that even a dark mountain can be paradise, if only we could see it in the right light.

Finally, many days after she was admitted to the ICU, my mother was released, and I flew back to be by her side. I thought back to the holy mountain and understood at last:

It’s the fact that nothing lasts that’s the reason that everything matters.

You Might Also Like