‘The Holdovers’ is an Elite-Tier Addition to the Boarding-School Movie Canon

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Seacia Pavao

From a distance, the campuses look just like those of the small colleges that dot the Acela corridor, the ones with the quirky mascots and the endless acapella groups. But wait for the class bell to ring and you’ll realize: Oh—the people walking out of these stark colonial buildings are children.

The American boarding school holds a special place in the national canon. It’s a staple setting on high-school reading lists (A Separate Peace), permeates preppy fashion, and provides an intriguing data point in a person’s bio, whether on Raya or in polite conversation. Boarding school is shorthand for things Americans otherwise tremble to talk about: class, inheritance, youth, potential, exclusion, secrets, intelligence, extroversion, power, fate.

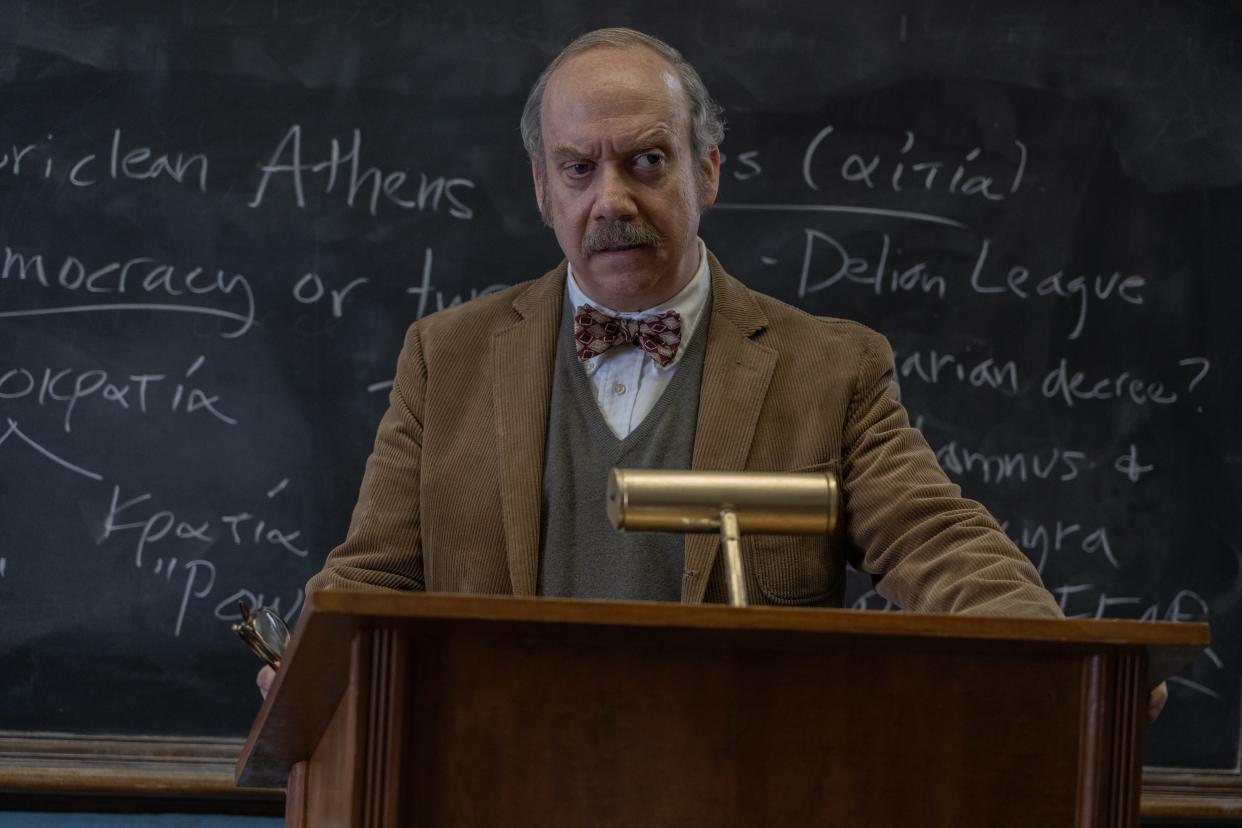

This winter’s The Holdovers is already one of the most humane, nuanced entries in the strangely durable genre of the boarding-school movie. It takes place over the 1970-1971 winter break at fictional Barton Academy, where snow pummels the campus and the Vietnam War ripples around the campus’s patrician buildings. Five boys have been left behind to weather the holidays under the watch of Paul Giamatti’s Mr. Hunham—the flinty, odd, wholly committed Classics professor—and Da'Vine Joy Randolph’s Mary, the head of the school’s kitchens, who works tirelessly as she grieves for her son, a Barton alumnus recently killed in Vietnam. Then one boy’s family, in a wonderfully American display of noblesse oblige, whisks all but one of the holdover students off to the ski slopes (the family chopper lands on a campus green and transports them to freedom), leaving behind the defiant, haunted, fundamentally decent Angus Tully (Dominic Sessa) to spend the holiday with the two adults.

What unfolds both deepens and subverts the boarding-school tropes as we know them. The Holdovers’ verisimilitude is unmatched. Director Alexander Payne filmed on location, shooting at Groton, St. Mark’s, Northfield Mount Hermon and Deerfield. The audience receives what OG preppy poet and St. Mark’s alum Robert Lowell called “the grace of accuracy”: the ageless stainless-steel pots in the kitchens; the narrow white hallways in the dorms, the terribly bright New England light lancing through old windows; athletics as a place of communal purification. Human accuracies radiate too. Hunham’s deepest academic passion isn’t vaguely Classical. He loves Carthage, the empire that resisted Rome and sent their biggest badass to lead armored elephants across the Alps. The vibes extend to the cast. Giamatti is a Choate alum. Sessa was cast when he was at Deerfield.

The fidelity doesn’t end at the chapel. Few of the movies in the genre leave any space for a world outside the campus, and if they do, it’s usually an analogous boys’ or girls’ school nearby.

Because The Holdovers’ story reaches beyond Barton’s confines, the world at large receives the same care as the campus does. When our trio go to a party thrown by a Barton staffer, the partygoers speak with the dropped r’s of Irish and Italian and Black and Portuguese Massachusetts. Our heroes visit crappy restaurants with gloopy desserts and faux-Tiffany lamps. When Tully gets into a teenage squabble with a boy who’s lost a hand in Vietnam, Hunham chastises him and Tully gets it. As a movie, it’s hard to investigate class if you don’t let the outside world breach the old-money one.

The Holdovers also leans beautifully into an often-skipped-over truth of American boarding schools: they were all designed by Calvinists and Episcopalians seeking to either replicate the grand schools of England or determined to reboot the concept with then-emerging 18th and 19th century educational theories from Europe. I don’t think I’ve seen a film that wears the intrinsic, impossible-to-escape religious spirit of New England boarding schools so meaningfully.

The trio of The Holdovers becomes a trinity. Mary is, well Mother Mary, all decency and endurance. But it’s not a perfect metaphor. We also see Mary drunk and furious with grief when the three characters go to that staff member’s party off campus: La Pietà with a Benson & Hedges, a glass of J&B, and existential anger. When the crew goes to Boston for a field trip, Mary visits her sister in Roxbury. Her family and the glimpse of Black Boston resists the film’s full gaze. We see but do not hear the exact conversation Mary has with her sister. That’s critically important. Their grief and memories and laughter remain a private, familial, holy thing. Mary’s son’s death in Vietnam is Christ-like in that he was clearly a good young man and because in an earlier scene Barton’s smarmy minister callously frames his death as the noble cost of business in America.

Giamatti becomes John-The-Baptist, the unhinged truth teller, aesthetically raw (he has a condition that makes his body reek and he has a lazy eye) but filled with messages about responsibility and life’s purpose that people must reckon with. Even his name—a half pun on “human” and “humble”—marks him as an outsider in a world of confidence and money. And Tully transforms into a kind of St. Augustine, a wild youth with a divine spark predicting the kind of man he will become.

In contrast to The Holdovers’ subtleties, mainstream boarding-school movies tend to paint only with primary colors. The whales of the genre—Dead Poets Society and School Ties and Scent of a Woman—play the hits: brutal old deans, saintly young teachers, bigoted goons, shitheel cheaters, admission to Harvard. These movies are OK and they will last forever.

As with private schools themselves, it’s the next rung down where the genre gets interesting. All I Wanna Do (1998) has a wonderful cast—Kirsten Dunst, Gaby Hoffmann, Merritt Wever—playing clearly defined characters launching themselves into the 1960s, arcing away from the life of Betty Draper and toward meaningful careers and identities. Selah and the Spades (2009) is notable in that it is set in a contemporary, co-ed school with a Black female protagonist. The story becomes Heathers meets The Warriors, all violent rivalries among the school’s cliques and drug use a plenty. Outside Providence (1999) is a funny, working-class academy fight song set in a second-tier boarding school. It’s essentially the Farrelly Brothers farting their way through a Robert Lowell poem. Maybe I’m biased as a native Rhode Islander, but the movie delights me. Think of it like a palate cleanser, a contrast to other boarding school movies similar to how Rhode Island is to Massachusetts: the weirder, looser next-door neighbor.

I’ll raise my hand for the flawed but underappreciated The Emperor’s Club (2002), the rare movie that centers a teacher’s experiences. Also set in the 1970s, the movie has Kevin Kline teaching classics (surprise!) to a motley crew of underclassmen: The naturally gifted student, the anxious tryhard (Paul Dano), and the charming, vulgar rich kid (Emile Hirsch) who—maybe just maybe—might have a real mind, if only Kline can refine it. What makes the movie interesting is that Kline’s teacher fails. He fudges the rich kid’s grades to get him into the school’s classics competition over Dano’s character. The rich kid cheats in the competition. Kline catches him. It doesn’t matter. He goes onto Yale and inherits his family’s wealth. But Dano’s character is devastated, and Kline is not promoted to headmaster because he’s been too focused on teaching and not on fundraising.

Even in these places, where the life of the mind is supposed to merge with starchy Protestant ideas of labor and character, connections rule. Years later, after Kline’s character has left teaching and has failed to launch his own career as a writer, he’s summoned to the once-rich-boy-now-rich-man’s resort to stage another emperor’s club competition. The prick secretly cheats again, and then announces his senate campaign. Kline returns to teaching, a little altered, a little resigned. The movie works because no one truly changes. Think of it as the sober, weathered version of Dead Poets.

I say this from lived experience: the greatest power that boarding school offers its students is refinement, not change. You come in adoring physics and you emerge well trained in superb laboratories from teachers who actively chose teaching high school over university tenure. You love literature? You’ll have senior electives on James Joyce and on the Harlem Renaissance equal to seminars at top universities. But you really won’t discover anything new about yourself. You will instead excavate yourself in a prestigious pressure cooker living alongside other kids doing versions of the same thing.

The absurd moments of The Holdovers—Tully leading Hunham on a chase across campus; the maintenance crew stripping down the holiday decorations the minute break begins—match the moments of campus chaos I lived through. I remember when a flinty, blisteringly smart zero-fucks-given girl in my class took a job at the town Friendly’s. When the academy’s deans found out, they demanded she give up the job. She instead quit the school and worked a few more shifts until she was recalled home. Our school’s rambling co-ed intramural soccer league was a collection of the last cuts from the extremely competitive varsity soccer teams, overwhelmed international students, fine-arts types who needed a fall sport, and the bad boys and girls who rolled into the games two shots of Southern Comfort deep. We could put whatever nickname, private joke or reference we desired on the back of our jerseys. One boy, beneficiary of a glow-up, lost his virginity to a girl from another prep school on a trip to China over the summer. Legend has it that this summer romance reached its peak on a quiet corner of China’s most famous monument. His goalie jersey the following season read GREAT WALL.

Where boarding school movies remain largely frozen in time, American college stories have caught up: The Sex Lives of College Girls feels like an accurate appraisal of the social and sexual politics of a tony, NESCAC-ish school. The Social Network haunts many a millennial striver. The twenty-year-old Undeclared remains relevant to the weird entropy and friends-by- convenience truths of the average college experience.

We could use a contemporary boarding school story. Boarding schools today are Blacker, browner places, more south Asian and east Asian, more Muslim and more Hindu, more publicly queer, with students more ready to raise their voice when it’s time to change the name on a building or fire a shitty teacher. Of course, these moments are filled with a little irony: deeply competitive young people talking about openness and inclusivity in some of the most exclusive and power-and-public-achievement centered institutions in America. The path from “prep school social justice activist” to “rising star at Meta or at Blackrock” is inevitable.

I think the world after boarding school has changed the institutions too. The contemporary college admissions process means that graduates of Exeter and Deerfield are no longer guaranteed spots in New Haven or in Cambridge. Look at any of the school’s college counseling pages. Yes, still lots of Harvard and Penn, but now with plenty of Wake Forest and Wisconsin and Kenyon. No one should ever cry over those colleges, but when in a previous era literally half the class went to Harvard and the other half to Yale, it’s a shift. I remember hearing a teacher at my school say with some sadness that the student’s peak experience at our academy was no longer graduation but instead receiving university admission. I’m still not sure how I feel about that sentiment.

Maybe the biggest change is that the boarding schools are simply more visible to the outside world. In my day one’s only visions of a school were printed lookbooks and the high-stakes pilgrimage of the on-campus visit and interview. Now their websites have a thousand photos of every campus corner, blogs from current students, and videos documenting an average day on campus and the pageantry of the big school rivalry days.

The darkness is more visible too. Student suicides at Exeter and at Lawrenceville made national news. Lacy Crawford’s 2020 memoir, Notes on a Silencing, is a harrowing account about the author’s sexual assault at St. Paul’s in the ‘90s. The Instagram account Black at Andover created a multi-generational record of campus racism from microaggressions to violence.

Some things remain. Though they are fewer in number now, there will be shiny, truly wealthy mediocrities who will slide into Dartmouth or Princeton because they will only ever be someone’s kid. You will have to play a sport every term. You will go to chapel. There will always be classmates better than you at the thing that you believe makes you special.

I wonder if the reasons kids seek these schools out has changed. At least among the people I knew, fewer kids were shoved into it. Boarding school was a choice. Why did I go? I had come to loathe my hometown, felt sad about how I was seen there, and wanted to leave. I was happy to be a nobody somewhere more exciting. For that deeply personal reason, I loved the minor characters in The Holdovers with whom we share only a moment: the Korean student dressed in a resplendent overcoat, weeping to fulfill a family legacy; the authentically cool and nice football player who is both very wealthy and seems only to care about being a teenager; the naïve Mormon boy who will always yield to authority. The mysteries behind these characters—we get no whiff of their dreams or of their fuller stories—spoke to me. It’s hard to explain this tension between intimacy and mystery among boarding school peers. Imagine becoming so close with someone that you feel like siblings, and yet you may never meet their parents nor see their childhood home.

At the same time, you were sharing bathrooms with them at sixteen. You heard them detail crush after crush. You sat with them on a cold slice of colonial land as their beloved cousin died thousands of miles away. You witnessed people you care about fail publicly: dropping pass after pass in a big lacrosse game; being the only one in their theater-obsessed circle not cast in the school’s big Shakespeare production; struggling earnestly in an advanced math class, tanking their transcript and their college plans.

Your version of your school disappears the moment you graduate. As much as these movies—and The Holdovers is absolutely one of the best ones—fixate on the past, boarding school itself is a record of impermanence. If you enjoyed your time there, it is a healthy early loss, an admissions ticket for adulthood. My guess is that The Holdovers will hold a special place for the average alumnus who will not live a public life, invent a chemical compound, win a Pulitzer, execute an international crypto scam and vanish, or pitch a war to the government. The Holdovers, like any meaningful school story, invites you to consider the oldest, most universal high school sentiment of all: In my day, it was like this.

Originally Appeared on GQ