The History of the Good Housekeeping Institute

Launched on May 2, 1885 in Holyoke, Massachusetts, Good Housekeeping magazine described its lofty mission as "to produce and perpetuate perfection — or as near unto perfection as may be attained in the household."

Today, Good Housekeeping along with its legendary consumer product testing facility the Good Housekeeping Institute and consumer emblems, the Good Housekeeping Seal and Green Good Housekeeping Seal, is an American institution. Purchased in the U.S. by Hearst in 1911, Good Housekeeping now has nearly 17 million readers of the print and digital editions, 45 million readers on its website, and almost 5 million social media followers.

Throughout its history, Good Housekeeping has been the go-to magazine for American women, providing them with news, trends, real-life and fiction stories, advice, recipes, and product recommendations. Famous writers who have contributed to the magazine include Somerset Maugham, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Betty Friedan, whose 1960 seminal article "Women are People, Too" was a precursor to her groundbreaking 1963 book The Feminine Mystique.

The Good Housekeeping Stran-Steel House at the 1933 Chicago World's Fair was a showcase for affordable, fireproof, prefabricated housing that blended modern technology and furnishings. Countless celebrities, political leaders, advice gurus like Heloise and Peggy Post, and famous chefs have been featured in the magazine.

Yet what sets Good Housekeeping apart from all other women's magazines is that its beauty, home organizing, cleaning, nutrition, cooking and home appliance, consumer electronic, and other product recommendations are based on the expertise of the Good Housekeeping Institute. And the thousands of recipes that are printed in the magazine, online, and numerous Good Housekeeping cookbooks are all triple tested in the Test Kitchen at the Good Housekeeping Institute.

Founded in 1900, the Good Housekeeping Institute was, at first, called the Good Housekeeping Experiment Station. The invention of electricity had introduced many new labor-saving home appliances but few consumers had any real knowledge of their operation and maintenance. With the goal of studying "the problems facing the homemaker and to develop up-to-date firsthand information on solving them," the staff at the GH Experiment Station tested products and housekeeping methods and published articles about their discoveries and observations. They also reprinted advice from readers who wrote them. One reader offered a cure for callouses (she used olive oil and cotton); another reader advised about how to launder lace drapes; and another gave tips about the best way to clean a meat chopper.

Concerned about adulteration and misbranding, home economists on staff also tested foods for purity and published, starting in 1905, a "Roll of Honor for Pure Food Products" each month. All this testing (at what was now called the Good Housekeeping Institute) resulted, in December 1909, with the beginning of the "Tested and Approved List" of all household products that were found to meet the Institute's standards of excellence. Good Housekeeping's Seal became so well known that, it has become part of the lexicon with celebrities, governments, manufacturers, basically — everyone — using it.

Today the Good Housekeeping Institute is located in the Hearst Tower in New York City and staffed by chemists, biologists, nutritionists, engineers, home economists, and culinary experts who evaluate thousands of consumer products each year, from microwaves and mascaras to vacuums and towels. These reviews are highlighted in the magazine and online. When products are evaluated for the Good Housekeeping Seal and the Green Good Housekeeping Seal — which both represent Good Housekeeping's two-year limited warranty, promising a replacement or refund up to $2,000 if a Seal product becomes defective within two years of purchase (certain exclusions apply) — promotional materials for the product are also reviewed.

From its beginning, Good Housekeeping has been a champion of consumer interests. Here are some of the highlights of Good Housekeeping's advocacy for American families.

1885

Good Housekeeping publishes its first issue in May 1885. The magazine's full title is Good Housekeeping: Conducted in the Interests of the Higher Life of the Household.

1885-1900

Good Housekeeping regularly publishes articles about food safety and food adulteration. Including ones about milk dealers adding water and dangerous preservatives to their product (September 1887), candy being contaminated with pulverized asbestos and other hazardous ingredients (February 18, 1888), adulterated chocolate (1886), spices and coffee. What begins as reportorial items in the magazine changes toward the end of the century when Good Housekeeping takes a more active role in calling for government action.

1900

Good Housekeeping opens the Good Housekeeping Experiment Station.

October 1901

Good Housekeeping launches a campaign for national pure food law ("A Campaign for Pure Foods: How Every Individual, Family, and Organization May Promote This Great War") and urges readers to write in for a packet of information about how to participate in the campaign.

1902

Good Housekeeping publishes a piece by Harvey Wiley on "Injurious Food Adjuncts" which addresses the problem of formaldehyde in infants' formula, milk and cream.

1906

Congress passes the Pure Food and Drug Act, which was endorsed and supported by Good Housekeeping.

1908

Good Housekeeping staffers persuade a builder and an architect to install the Experiment Station sinks at a comfortable 36 inches, which establishes the standard height for all kitchen sinks and counters. Before this, sinks were built low to the ground, requiring users to bend over.

1909

The Good Housekeeping Seal launches with a list of twenty-one consumer products are listed in the issue. Any product that withstands the investigation of the Institute staff is eligible to be included in the newly developed "Tested and Approved" products to be published in the magazine.

1910

The Experiment Station is renamed the Good Housekeeping Institute, a facility on the street level of the Good Housekeeping building in Springfield, Massachusetts which included a model kitchen, domestic science laboratory, and test stations.

1912

Thomas Edison predicts in a GH interview the liberating impact electric household appliances will have on American women.

Dr. Harvey Wiley, "the Father of the Pure Food and Drug Act," leaves his position in the Bureau of Chemistry at the Department of Agriculture (now the FDA) in Washington to become the GH Institute's director of the Bureau of Foods, Sanitation and Health. His articles in Good Housekeeping about deceptive food labeling and practices and food safety problems as well as his answers to reader questions in the "Question Box" feature often reflect wisdom and insights that are way ahead of their time.

Who was Dr. Harvey Wiley? It's a sweet story: Honey turned Harvey Wiley, M.D., the Institute's longtime Director of Food, Sanitation, and Health, into a passionate consumer advocate. Born in 1844, Wiley fought in the Civil War, went to medical school, then taught chemistry. In 1878, fiddling with a polariscope, a device for measuring stress in glass, Wiley examined various transparent foods and was shocked to learn that what companies were passing off as pure honey was mainly glucose. Thus began his lifelong campaign against mislabeled and dangerous products. He spent 29 years as the chief of the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Bureau of Chemistry, where he fought for the passage of the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act. At GH from 1912 to 1930, he alerted readers to food frauds such as the treatment of spoiled vegetables with chemicals to "revive" them. In 1911, Wiley sued Coca-Cola for failing to label the soda as containing habit-forming caffeine. He lost the headline-making case, but it paved the way for future truth-in-labeling laws.

1913

At a time white rice and white bread are touted as "pure," Dr. Wiley urges Good Housekeeping readers to recognize the nutritional benefits of whole grains.

1914

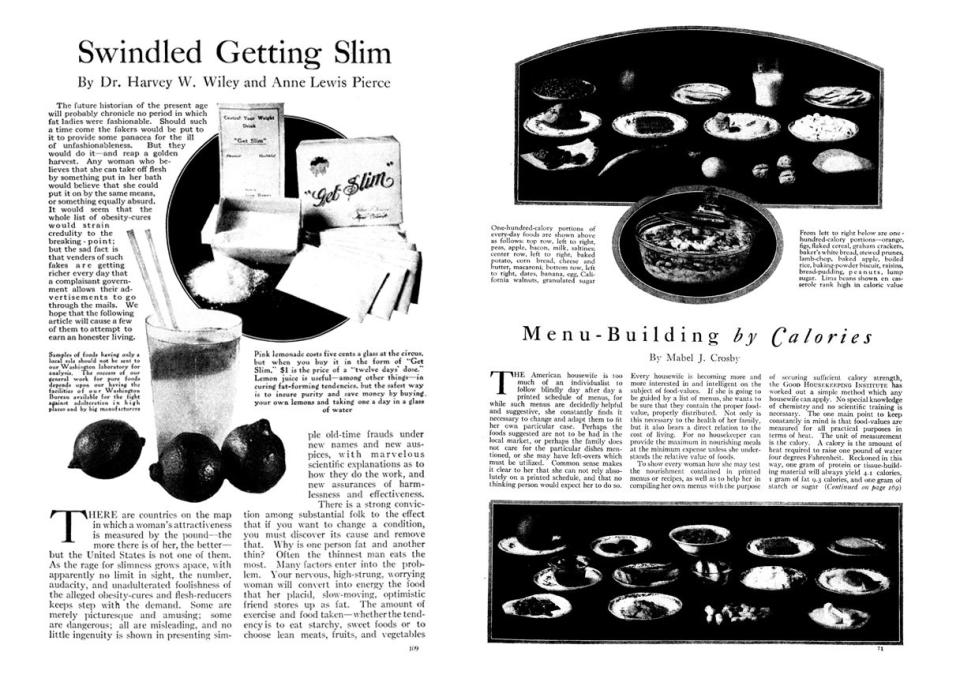

An article entitled "Swindled Getting Slim" warns readers about fad diets, "Don't believe anyone who tells you that you can reduce your weight with no injury to your health without dieting, exercise, and right living … Overeating and under-exercising are the main causes of too much fat."

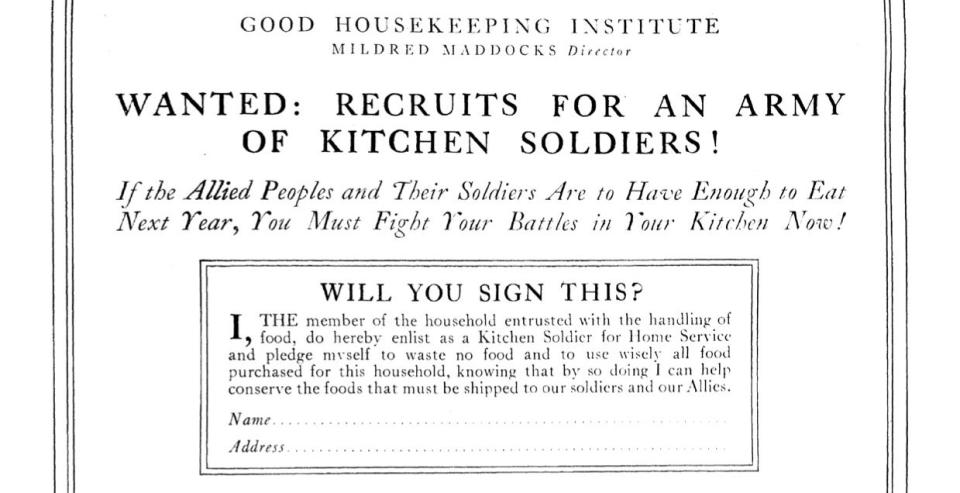

1917

An editorial depicting women's domestic work as part of the U.S. military effort solicits women as "kitchen soldiers," asking readers to sign a pledge to conserve food. "Once you have enlisted as a Kitchen Soldier, your kitchen is your battlefield. There you must fight your fight….When you hit upon a good idea, sit down and write to us. Tell us how you found that you could get along without some food that may mean life and comfort to a soldier in a foreign trench. Tell us new combinations, new substitutes, new shortcuts. We want a flood of letters bearing your discoveries."

1921

Dr. Wiley urges Congress to pass the Maternity Bill of 1921, which allocates federal funds for improved infant care; this bill eventually leads to lowered infant-mortality rates.

1927

Dr. Wiley warns women about the dangers of too much sugar consumption: "The trouble with sugar is we use entirely too much of it. At present time we consume about 100 pounds of commercial white sugar per person per annum."

1928

Dr. Wiley alerts readers about the dangers of tobacco, "Cancer of the lips, tongue, and throat is much more prevalent among men than among women, I consider this due to the use of tobacco, particularly smoking."

1930s

Women enter the factories and spend less time at home; food editor, Dorothy Marsh, begins her "60-Minute Menu" series, which helps women cook a nutritious meal after long a day at work.

1932

Way before the role of sugar in tooth decay is firmly established, GH warns readers, "an excess of sweets encourages the development of the organisms in the mouth which attack tooth enamel and thus initiate the first stages of decay."

1941

The Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval is changed to the Good Housekeeping Seal. Products advertised in the magazine that bear the Seal are tested by the Good Housekeeping Institute and are backed by a two-year limited warranty.

1943

The Institute's Baby Center opens, which anticipates American servicemen coming home and the "Baby Boomers."

1952

Good Housekeeping stops accepting cigarette ads due to harmful effects on health. This is 12 years before the Surgeon General issues a report on the health hazards of smoking.

1969

Good Housekeeping endorses the Child Protection and Toy Safety Act, which calls for more strenuous screening of toys, and goes further by rejecting ads for toys with sharp edges or small parts that pose chocking hazards.

1972

The Good Housekeeping Institute helps establish clothing care industry standards, which leads to the Clothing Care Labeling Law, which mandates care instructions on garments.

1983

A monthly section devoted to reporting on microwave innovations and microwave recipes.

1998

After a reader whose child was strangled by an ill-fitting crib sheet alerts Good Housekeeping, the Institute tests crib sheets and finds that most are too small or use poor-quality elastic. This causes the sheets to come off the corners of mattress, which increases the risk of infant strangulation and suffocation. The Institute set a new crib sheet standard, which is being evaluated by the American Society of Testing and Materials.

2000

The Institute finds that certain children's bicycle helmets fail to meet the federal Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) safety standards. As a result, the CPSC recalled more than 240,000 helmets, the largest bicycle helmet recall in history.

Also, in 2000, the Institute has consumers use standard fire extinguishers and finds that most are used improperly. The Institute provides advice on how to properly use extinguishers.

2003

The Good Housekeeping Institute tests water toys and finds some that pose serious hazards.

2001, 2003, 2010, 2014

The Good Housekeeping Institute evaluates Halloween costumes for children and identifies some that don't meet federal flammability standards.

2004, 2006

The Good Housekeeping Institute's Nutrition Department identifies packaged foods whose labels misrepresent a typical "serving." For instance, one donut's "serving" was one-third of the donut; a cookie's "serving" was listed as half a cookie.

2005

The Good Housekeeping Institute warns that some children's skateboards and power scooters go dangerously fast and have inadequate brakes and helps draft new safety standards.

2006

The Good Housekeeping Institute moves into the LEED-certified Hearst Tower in New York City, the first "green" office building in NYC.

2006

The Good Housekeeping Institute's Textile Director investigates high thread-count sheets at low prices.

2007

The Beauty Lab tests moisturizers and finds that a $25 cream keeps skin more hydrated for a longer time than the more expensive creams (even the $350 one).

2008

GH engineers test pool alarms and find that three failed. Readers are encouraged to send letters to their representatives in Washington to support the Virginia Graeme Baker Pool and Spa Safety Act, which became effective on December 19, 2008.

The Home Safety Council presents Good Housekeeping with a Beacon Award for accurate and educational reporting and for helping Americans understand what they can do to be safer in and around the house.

Plastic wraps and food storage containers are tested to determine whether potentially dangerous chemicals leach from them into food during microwaving. No BPA or phthalates are detected in our zapped samples.

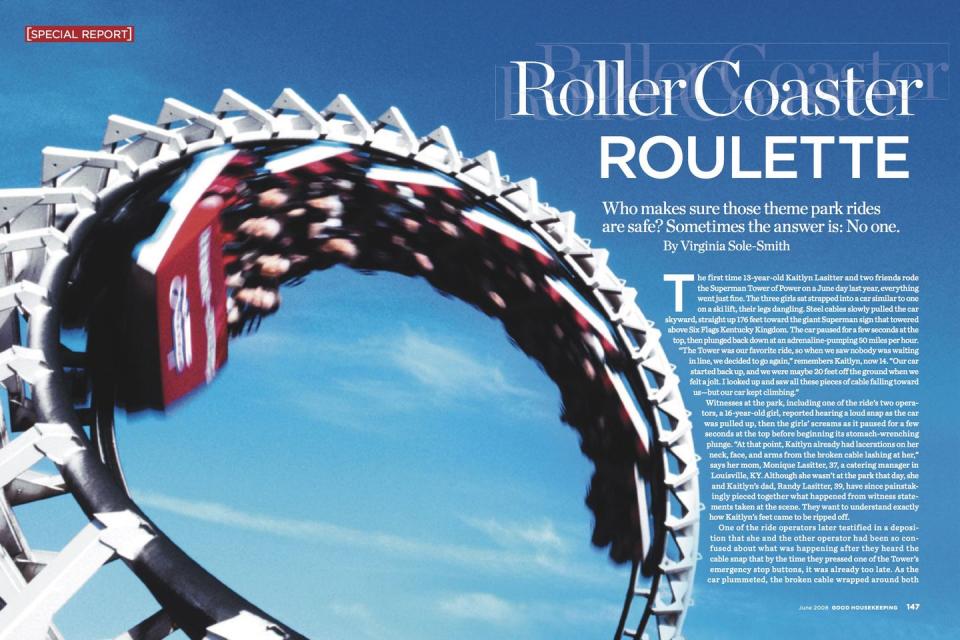

Good Housekeeping publishes a special report called "Roller Coaster Roulette" and asks readers to write their state representatives to co-sponsor the National Amusement Park Ride Safety Act.

The first annual Best Toy Awards are published in the December issue. All toys are vetted by kid-testers and examined by Good Housekeeping Institute engineers to ensure they conform to industry safety standards.

2009

Nineteen thermal containers are tested by the experts in the Kitchen Appliances and Technology Lab and only one is found to keep food safe at hot or cold temperatures.

GH's Textiles Lab alerts consumers that because of chemical processes, bamboo fabrics are no more environmentally friendly than rayon. Months later, 78 retailers are warned by the FTC to stop labeling products "bamboo" as a way to suggest greenness.

Good Housekeeping introduces the Green Good Housekeeping Seal, an environmental emblem that includes comprehensive life cycle criteria.

2010

The Good Housekeeping Institute tests earrings and necklaces marketed towards children at leading retailers for heavy metals, including lead and cadmium. All items contain lead at levels well above the government's limit in children's products and many also contain cadmium.

The Home Appliances and Cleaning Products Lab investigates household products with packaging that may pose safety risks to children, including air fresheners that look like bowls of candy and all-purpose cleaners that could be mistaken for sports drinks.

3-D glasses given out at movie theaters are found to harbor bacteria, with one being potentially lethal bacteria. The Institute recommends bring along an alcohol wipe to movie theaters to reduce bacteria more than 95%.

The Good Housekeeping Institute recruits families across the country with children under the age of 3 to visit local fast food restaurants and request special toys for younger children with their kids' meals. Nearly all of the 15 locations gave out toys to toddlers that are only appropriate for older children due to small parts that pose choking risks.

While evaluating full-size strollers, the Good Housekeeping Institute discovers more than a quarter of those tested pose potential hazards to young children. GH urges the industry to address a loophole in the safety standard regarding the hood's hinges. In 2013, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) votes to approve a proposal to create a federal safety standard for strollers.

2011

Four salon keratin hair treatments are tested for formaldehyde. The toxic chemical is found in all four products, at levels exceeding the Cosmetic Ingredient Review's 0.2% recommended threshold. Later that year, the FDA issues a warning letter to the distributer of one tested brand for falsely labeling the product as "formaldehyde-free" or "no formaldehyde." The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) issues a hazard alert later that year regarding keratin treatments and the risk to salon workers.

Children's rain jackets are tested and found to exceed the Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act's limit on lead and phthalates.

Sand from five out of nine backyard sandboxes across the country test positive for the E. coli bacteria and seven for two types of roundworm eggs.

Good Housekeeping launches an annual review of cars, taking into consideration road and highway performance, gas efficiency and numerous family-friendly features.

Top-brand mugs are found to contain lead and arsenic, although neither leached out during tests. Some registered surface temperatures of over 140°F, hot enough to burn skin and above the voluntary standard. GH urges the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) to mandate that ceramicware pass temperature tests before it can be labeled "microwave-safe."

2012

The Good Housekeeping Institute tests the accuracy of drugstore blood pressure monitors and finds that nearly half of the readings were off by more than five points compared to those by a nurse practitioner. None of the four machines contained accurate guidelines.

Nearly half of workout weights deviate from the weight claimed and in pairs of weights, over a quarter of the mates don't match.

Portion deceptions are discovered at popular national restaurants, including a "Pizza for One" listed on the restaurant's website as having the equivalent of four servings. GH urges readers to check restaurant websites for serving sizes and nutritional information before ordering.

2014

Seven mini flat irons reach average temperatures of 230°F (above water's boiling point of 212°F) posing burn risks to skin and scalp.

2016

The Good Housekeeping "Nutritionist Approved" Emblem is launched. The program is led by the Nutrition Lab (overseen by a registered dietitian) and is designed to help consumers simplify the process of making informed food choices.

You Might Also Like