History: Celebrating the vision, engineering that made Palm Springs Tram possible

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Daniel Burnham, the architect of the 1893 Columbian Exposition, knew how to think big. For that fair, he conjured up from his imagination an entire city, complete with roadways, lakes, bridges, parks and enormous buildings. He counseled thinking on the grandest of scales:

“Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men’s blood and probably themselves will not be realized. Make big plans; aim high in hope and work.”

Half a continent and half a century away, in 1930s California, the publisher of The Desert Sun newspaper Carl Barkow and electrical engineer Francis Crocker aimed extremely high in hope and work. They were exceedingly parched during the heat of the day on a road trip to Banning and looked up at the peak of Mount San Jacinto wishing they could be magically transported from the harsh desert up to the cool snow.

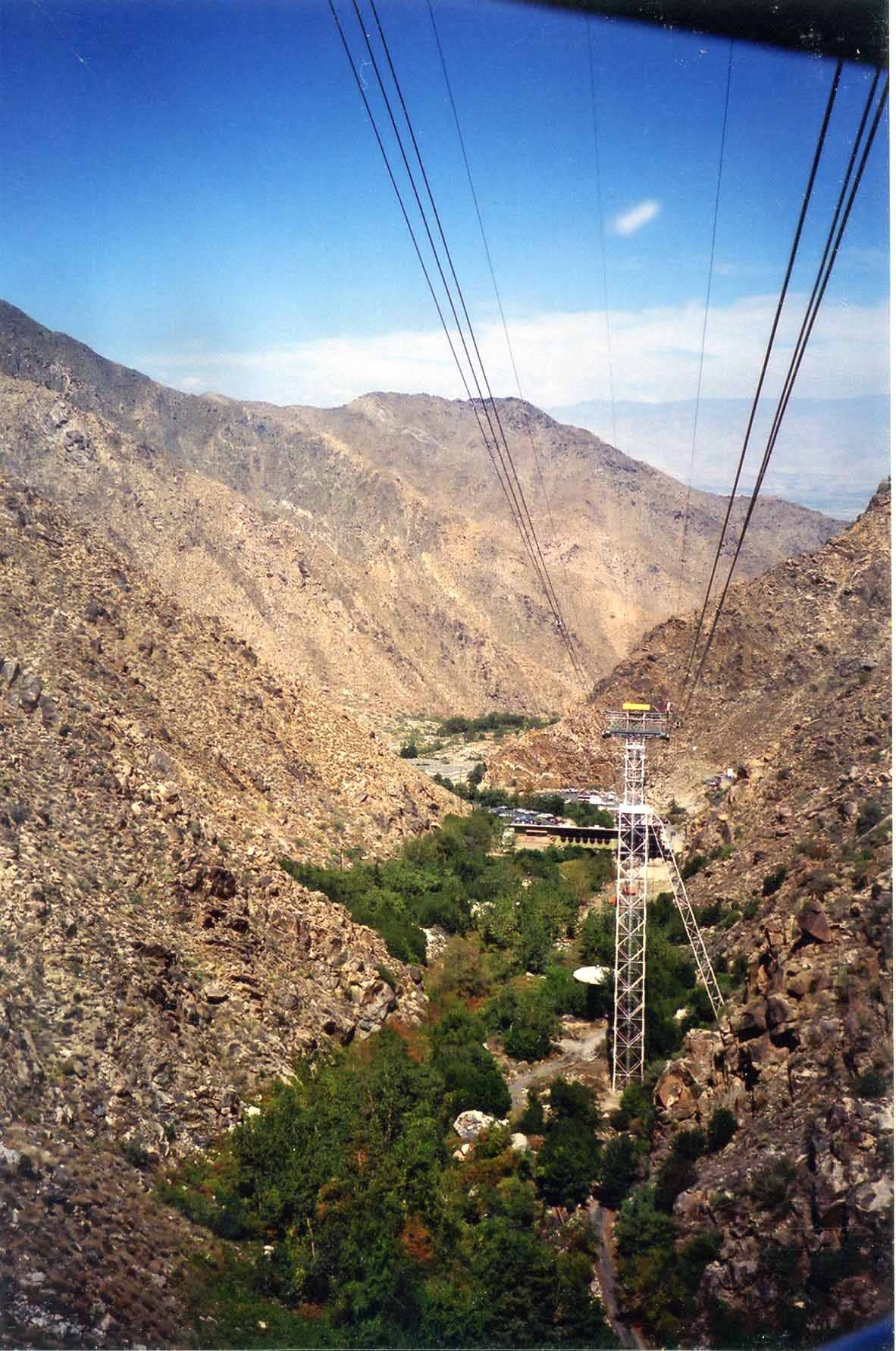

It gave Crocker an enormous idea. The engineering feat required by Crocker’s imagination was unprecedented in its scope and daring: a funicular from the valley floor to the mountaintop. It was no little plan.

Due to the continuing Depression and then second world war, the idea languished. It was an unprecedented undertaking, an unlikely project, literally aiming high. But Crocker had worked on the Hoover Dam, so he understood big projects and asked his friend Earl Coffman, of the famed Desert Inn to help.

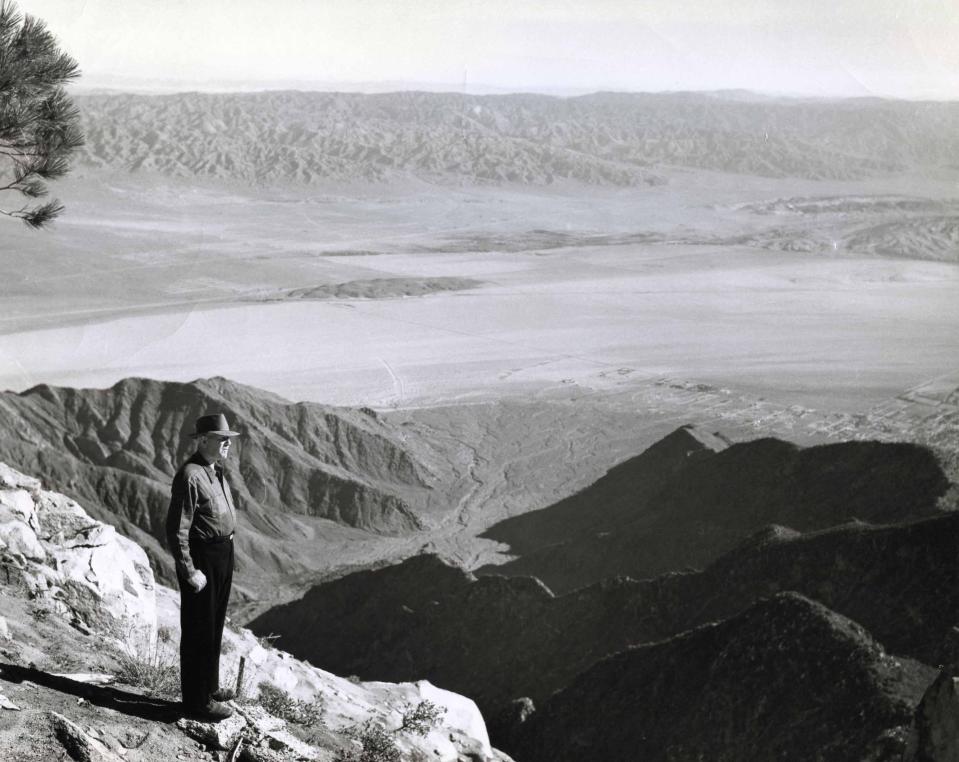

Coffman’s grandmother, Nellie, had gazed down from that same mountaintop in 1908 and decided to make her way to the tiny village of Palm Springs, starting a destination resort town.

The funicular, or tramway, as Crocker and Coffman called it, would allow visitors to have the same view Nellie had enjoyed of the outstretched valley below without the trouble of hiking from Idyllwild.

The idea captured Coffman’s imagination and stirred his blood.

For the ensuing two decades, Coffman worked tirelessly on the tram. He arranged for the financing with a bond. He and Crocker pressed prominent local citizens, from Warren Pinney, manager of the El Mirador Hotel, to George Wheeler, publisher of the Palm Springs Villager, into service. They elected erstwhile mayor of Palm Springs Phil Boyd to the State Assembly to help pass the required legislation. Governors who were not enamored with this big plan twice vetoed the bill that would have created the necessary entity.

Finally, in 1945, new legislation authorized the tramway and Gov. Earl Warren, who would become Supreme Court chief justice, signed the measure creating the Mount San Jacinto Winter Park Authority. Edmund “Pat” Brown was an important proponent. Coffman was named the authority’s first chairman and Crocker was named the first secretary.

By 1950, the many technicalities and complexities of building a link between the valley floor and the top of the mountain were being solved. Funds for the construction were raised by the sale of $8.15 million in private revenue bonds. (No public funds were used for either the construction or operation of the tramway. The 35-year bonds were successfully paid off in 1996.)

Culver and Sallie Stevens Nichols donated the land for the Valley Station, parking lots and the first tower.

Every bit of architectural prowess the little town of Palm Springs had to offer was enlisted. Albert Frey, Robson Chambers, John Porter Clark and Stewart Williams all contributed, producing stunning mid-century buildings for the stations between which the tramcars would travel.

Construction began in 1960. Helicopters were required due to the steep and inaccessible terrain. Don Landells led the team that carried men and material up the Chino Canyon escarpment. Equipment was disassembled and airlifted piece-by-piece, then reassembled on the mountain. Six pilots flew three helicopters in six-hour shifts for a two-year period, slinging their payloads up the mountain.

Thirty-five full-time construction workers lived in prefabricated houses at the site. They commuted to the job by helicopter on Monday mornings and returned to the valley floor on Friday evenings. The tramway would eventually be designated a civil engineering landmark for this remarkable feat of aeronautic ingenuity.

The original, official souvenir guide to the Palm Springs Aerial Tramway was called Tramway-Land. In its opening pages, Pat Brown, by then the governor of California, proudly greeted visitors with a letter that quoted an inscribed plaque on one of the State’s capitol buildings: “Send me men to match my mountains.”

In June 1963, two such men, the resident engineer and general foreman of the project took the first trial ride on the completed Tramway. Dignitaries would follow after the requisite ceremony and speeches.

Last week 60 years later, the tramway celebrated that first ride. The anniversary is also marked by the publication of a new, exquisitely researched and extensively illustrated book that explores the previously unknown history surrounding the Tram by Steve Lech entitled “Crocker’s Folly.”

Lech, for the first time, chronicles the opposition to the construction of the tram and the first large-scale environmental battle in Riverside County over its construction. (The book is available for purchase at the Palm Springs Historical Society.)

The engineering and logistics of building the tram were perhaps the easier of the difficulties to be overcome. The Desert Sun Editorial Board in 1960 summarized, “Were it not for the opposition of a small but somewhat influential group of conservationists, the Mt. San Jacinto passenger tramway would likely have been built several years ago. While they were never able to block the legislation that authorized the project, their harassment tactics caused numerous delay sand made the work of the Tramway Authority a great deal more difficult.”

“This group of organized conservationists took the position that the scenic and primitive area which the tramway would make accessible to millions should be preserved for the few rugged individuals who could hike or pack in from Idyllwild.”

Lech recounts the opposition and the concessions environmentalists were able to win from the authority in order to limit the deleterious effects on the wilderness.

The Desert Sun continued, “They opposed the project in spite of the fact that the area made accessible was limited in size and could not be commercialized. This protection was assured by a contract between the tramway Authority and the State Park Board. The Desert Sun has always taken the position that thinking on the part of these organized conservationists was narrow and selfish… No one can deny that it would be one of the state’s greatest outdoor attractions…(Conservationists) will find that sentiment has changed over the years—like the engineering advancement that would make it possible to build the tramway in one span instead of two as originally planned.”

Crocker died in 1997 after many trips up the mountain in his improbable but realized grand dream. Decades before, he had looked up with hope and determination at the snow-covered peak of the mountain, made no little plan, and matched it.

Tracy Conrad is president of the Palm Springs Historical Society. The Thanks for the Memories column appears Sundays in The Desert Sun. Write to her at pshstracy@gmail.com.

This article originally appeared on Palm Springs Desert Sun: History of Palm Springs Aerial Tramway