Hiroki Nakamura’s Guide to Shopping, Eating, and Hot Spring-ing in Tokyo (and Beyond)

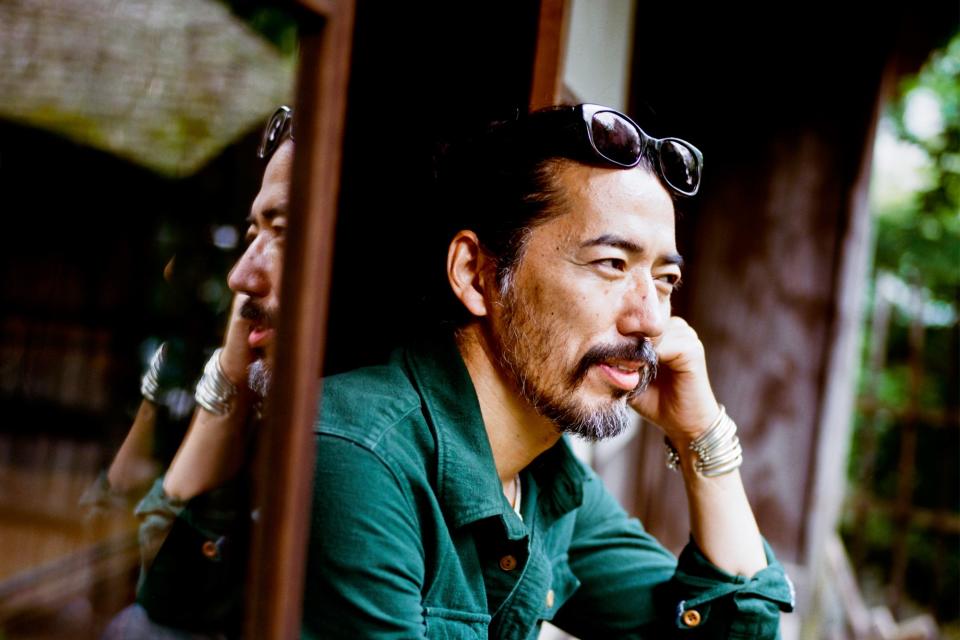

In his pop-up store in New York City, which ran from September to December, designer Hiroki Nakamura sat down on a sofa with oatmeal-hued cushions in front of a matching black walnut wood coffee table. Both were made by the late and legendary Japanese-American woodworker George Nakashima, who incorporated Japanese joinery and Shaker and modern styles into his work and pioneered the “free edge.” Nakashima, whose memoir was called The Soul of a Tree, wrote in spiritual terms about his materials, and sitting in front of that coffee table, you could feel its soul, too.

“Why does this table speak to me?” asked Nakamura, the philosophic designer behind the cult Japanese workwear brand Visvim. “I want to find out.” It’s the sort of question—why some objects have a spiritual power and others don’t—he has been pondering since he was a teenager hunting for vintage Americana in Tokyo, and it's a way of looking at his craft that he shares with Nakashima. Also like Nakashima, he draws on cross-continental influences for his clothing line: a trademark blend of Native American and Old West sensibilities along with traditional Japanese textiles and workwear.

It was curious to see pieces from Nakashima, whose work is also on display in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, in a temporary retail space, where throwaway white display cases are more typically the norm. But nothing is quite usual about Nakamura’s approach to selling clothing.

Until this past year, the 18-year-old brand had no standalone stores outside Japan, where it now has seven locations. Last July, Nakamura debuted his first American store, with his signature fringed “FBT” moccasin sneakers, worn indigo denim, and nylon kimono jackets, in New Mexico of all places. “I love Santa Fe, all the craft, all the culture. I wanted to start with something not so commercial,” said Nakamura, when asked why he didn’t begin his international expansion in a larger U.S. city. “I still need that connection to my soul. It’s a business, but I don’t want to forget where I started from. If I forget, my product will lose its spirit, you know what I mean?”

The soulful nature of Nakamura’s clothing is what draws fanatical collectors like Kanye West, Eric Clapton, and John Mayer, who reportedly wears little else. Nakamura is known for meticulously sourcing materials like Egyptian Giza cotton, the highest-grade cotton in the world, and using old-world techniques to create brand new garments. He is particularly keen on the craft of the everyday. “Between the 1920s and 1960s in Japan, there was a big craft movement, the mingei movement,” says Nakamura. “I was inspired by that movement. I like things designed for a purpose, for a reason. I think those things are beautiful, too. There’s a reality to them.”

With that attention to craft and quality in mind, we asked Nakamura where he goes to shop, eat, and get inspired in Japan. Here are his favorites.

Where to Shop

Whenever Nakamura is back in Japan—he avoids the crazy humid summers, going in winter, spring, or fall instead—he tries to catch the massive flea market at Kyoto’s Toji Temple, which is held on the 21st of every month. If you’re used to parking-lot flea markets with piles of broken plastic doodads, this is a different thing entirely. The Toji Temple, which dates back to the 700s during the Heian period, is a UNESCO World Heritage site, and the vibe is less junk pile than antique treasure hunt. “Most vendors are selling old folk Japanese stuff, mingei stuff,” says Nakamura, gesturing behind him at the large paper koi. “You can find things like this paper koi and old kimono or beautiful handmade bags made out of grape vines.” There are also iron tea kettles, figurines, and boro (patched indigo textiles), plus, as it’s Japan, there are plenty of food vendors, too.

Now that Nakamura splits his time between Los Angeles and Tokyo, he no longer hunts for Americana in Japan like he did when it was foreign exotica to him, but encourages travelers to do so. “In the ’80s and early ’90s, there was a big movement of Americana vintage, so a lot of good American workwear, denim, leather jackets, motorcycle stuff went to Japan,” he says. Meaning that if you’re a collector of American vintage—and if you are, you probably already know—the place to find the best and best-preserved specimens is actually Japan, at shops like Tokyo’s Hinoya and Sunhouse. There are also plenty of smaller shops, as well as the twice-annual Antique Jamboree, held in January and August, that showcases a mix of American, European, and Japanese wares.

When I pressed Nakamura on other places to shop, he kept returning to the Toji flea market and its many, many vendors. But for those whose vacation timing doesn’t align with the larger markets, he recommends Takumi Craft Shop in the Ginza neighborhood of Tokyo. “When you go to Japanese antique shops, you can find things like a miso soup bowl for just $5 from the Edo period, which is like 15th or 16th century,” says Nakamura. “There’s a lot of old things in Japan. It’s amazing.”

If you want to go straight to the source, Nakamura, who has spent decades now seeking out the world’s best craftspeople, suggests excursions to Kanazawa, home to a vast range of traditional crafts, including silk dyeing, musical instruments, and porcelain—as well as a Visvim outpost—and Mashiko, a famous pottery town, where you can find 380 styles of ceramics. Both are about an hour's train ride from Tokyo. “I also love Okinawa,” says Nakamura of the tropical island in southern Japan, which is home to the katazome, a dyeing technique done with rice pastes and stencils. “The color is a little happier, and they use motifs of fishes and shrimps. It’s really cute.”

Where to Stay

“Fujiya Hotel in Hakone is one of my favorite hotels in the world,” Nakamura says of the hot springs resort hotel founded in 1878 in a suburb of Tokyo. “In Japan, there were only ryokan [a traditional Japanese inn] during the Edo period, so when people from U.S. or Europe start coming in the late 19th century, they start building hotel, mixing Japanese ryokan architecture and hotel. It’s super cool.” The Fugiya Hotel is located in an onsen, or hot springs area, and features multiple baths, including one crafted from hinoki (cypress wood), drawing on the local hot spring waters.

Where to Eat

Despite all the eminent kaiseki, soba, and Michelin-starred restaurants in Tokyo, the first place Nakamura told me to go eat was a fruit shop, albeit a world-famous one: Sembikiya‘s flagship in Nihonbashi. “They have the best fruit, like $200 mango,” says Nakamura. “We just order the parfait—it’s so good.” To the untrained eye (or palate), Japan’s fruit prices may seem exorbitant, but Japanese farmers treat their produce in a way that's almost unheard of elsewhere, wrapping fruits individually while they’re still on the tree to prevent bruising or over-ripening. It is common in Japan to give expensive fruit as a gift. “You know shokunin?” asks Nakamura. “It’s craftsmen culture. In Japan, there’s a respect to craftsmanship, which I think is cool. Japanese fruits have been taken care really well, that’s for sure.”

If a simple piece of tenderly cared-for fruit is on one end of the spectrum of elemental pleasures in Japan, sushi is on the other. Nakamura’s favorite sushi restaurant is actually located about an hour outside of Tokyo in Kanazawa. Sushi Dokoro Mekumi, located in a residential neighborhood, has only five or six seats and books out months in advance. “To me, he is the best,” says Nakamura of chef Takayoshi Yamaguchi, who named the restaurant after his wife. “His work is just unbelievable, like art. I like sushi chefs because they’re pushing their craft, like shokunin. They take it really seriously.”

In Tokyo, Nakamura’s go-to is Sushi Sho in Yotsuya. The restaurant is now run by an apprentice of its founder, Keiji Nakazawa, who decamped for Hawaii in 2015. Legendary in Tokyo, Nakazawa pioneered the resurrection of Edo-style sushi, made with aged fish and stronger vinegars, that is the standard in the best sushi restaurants today. “He told me he left Tokyo because Tokyo sushi chefs are too spoiled; they have access to the best material,” says Nakamura, laughing. “In Hawaii, he wants to challenge himself to use local fish and materials. I went there for Thanksgiving, and it was amazing. Somebody like that is really inspiring.”