I Hiked the Ancient Trans-Bhutan Trail When It Reopened After 60 Years — Here's What It Was Like

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

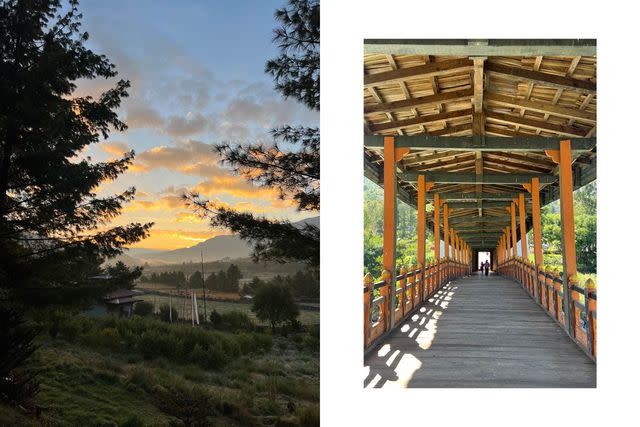

The 250-mile trail officially reopened in September.

Heather Richardson

Hearing my breathing, you might have thought I’d just finished a flat-out 400-meter sprint. My erratic panting was alarming enough for Tshering Tobgay, my Bhutanese guide, to kindly pause for frequent breaks along the 2,000-foot ascent — a trail steep enough in parts to force me onto tiptoe. Eventually, we reached the top, 11,150 feet above sea level, and I plopped down on a convenient wooden bench. A cool breeze rustled the leaves. A gap in the tall, slender blue pine trees revealed a swath of thick, lush forest at the bottom of the valley and a range of shadowy peaks beyond.

The first climb of my 10-day, 90-mile hike along the Trans-Bhutan Trail (TBT) was, thankfully, the hardest; I soon acclimatized and found my climbing legs. This was fortunate because in the mountain kingdom of Bhutan — a tiny country sandwiched between China and India — there's no shortage of uphill slogs.

Heather Richardson

Heather Richardson

The TBT runs 250 miles across the middle of Bhutan, connecting trails from Haa in the west to Trashigang in the east, topping out at around 13,000 feet. The paths lead through dense pine and rhododendron forests, around crumbling Buddhist stupas, across frothy blue rivers, up to high mountain passes with fluttering Tibetan prayer flags and views of snow-capped Himalayan peaks, through tiny farming communities and rice terraces, and into pocket-sized towns on the valley floor.

While serious trekkers will be drawn to the northern Himalayan region of Bhutan, the beauty of the TBT is its accessibility. As walkers are never too far from a road and the luggage-carrying support car, it’s easy to mix and match sections to suit fitness and ability, and hikes can be cut short on the fly — a relief on a day I was already struggling with an upset stomach before encountering a swarm of angry bees.

Heather Richardson

Although officially reopened on Sept. 28, the only new thing about the TBT is the name; the trails are hundreds of years old. Up until the 1960s when the first roads were built, everyone — traders, pilgrims, messengers — had to journey on foot or by horse, mule, or yak. Parts of the TBT were used by Bhutan’s second king to move between his summer and winter residences from the 1930s to the 1950s. On one section, I was joined by 64-year-old Dawe Tshering, who was a postal messenger using these paths to verbally relay messages between villages before roads and phones reached his community in the early 2000s. He’s only ever led five tourist groups along this trail — most take the road, he said — but the marketing of the TBT will likely see many more people hiking through open fields, past yak herder camps, across bubbling streams, and into the forested valley below, hosted for a hearty lunch of buckwheat pancakes and spicy dried beef in a village along the way.

The idea of restoring these cross-country footpaths came from Bhutan’s fifth king, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuck. The Bhutan Canada Foundation funded the clearing and signposting of the trails — carried out by teams of local volunteers during the pandemic — and the establishment of TBT, a nonprofit organization that created a series of itineraries for international tourists. By tidying and marking the trails, TBT also hopes to encourage more Bhutanese to use these old paths.

Heather Richardson

Today, even in places connected by roads, the king is known to hike between villages — and it seems some have taken to emulating His Majesty’s love of walking. We met a group of local dignitaries at the sacred site Toeb Chandana — the legend goes that Drukpa Kunley, the Divine Madman, shot an arrow from Tibet, which landed here in a still-preserved 15th-century staircase — and I noticed that all their hiking boots, lined up outside the temple, looked suspiciously new.

I visited shortly after Bhutan reopened its borders on Sept. 23, following a 2.5-year closure during the COVID-19 pandemic. It was a difficult time; tourism is the second biggest industry after hydropower. But the government didn’t want to reopen until most people over the age of five had been vaccinated.

Heather Richardson

This cautious attitude extends to Bhutan’s tourism strategy, which has followed a "high value, low volume" model since first welcoming travelers in 1974. To that end, the daily Sustainable Development Fee was upped this year from $65 to $200 (previously exempt regional tourists now pay $15). It’s not a universally popular decision in Bhutan. As wealthy travelers who can afford the tax will typically favor luxury hotels, tourism professionals fear that mid-range properties, guides, and Himalayan trekking operations are likely to lose business under the new entry requirements. One of the positives of the TBT is that the trails are punctuated with many such hotels and homestays, which may prompt some visitors to diversify their accommodation choices.

It is possible to loosely link a circuit of luxury hotels with day hikes, but I opted to bookend my trip with high-end resorts instead. On arrival, I stayed at Six Senses Thimphu (the brand has five hotels in western and central Bhutan), which overlooks the fast-growing capital, the giant golden Buddha statue, and the snowy peaks beyond. It was a blissfully tranquil place to recover from a long, three-flight journey. A traditional, herb-filled hot stone bath nearly boiled me alive, but many swear by the piping hot waters for a restorative soak.

Heather Richardson

While hiking the TBT, I stayed at three-star hotels, homestays, and campsites.

At a camping spot in central Bhutan, I awoke one morning to find my water bottle frozen solid. Peering outside, I found the surrounding farmland fields covered in pearly frost over which ice-blue mist hovered in the weak early light. It’s testament to the snugness of my camping bed that I didn’t notice the sub-zero temperatures overnight. At another site, my sleep was less restful thanks to dogs incessantly barking and the village cows farting directly outside my tent.

In the east of Bhutan — a quiet, rural region, far less visited than the west — I stayed with a Buddhist lama named Ugyen Wangdi. He’s lived there his whole life and — unlike many who have relocated to the capital of Thimphu in recent years — has no desire to move elsewhere. “It’s simple,” he said of his valley, its scattering of whitewashed stone houses with corrugated metal roofs set between crop fields, rice paddies, and forested hills. “Peaceful.”

Heather Richardson

When I told him I lived in South Africa, he opened Google Earth on his phone to find the country and, zooming out to the continent, had many questions about Africa: Are there sacred sites? Forests? Religion? Do people like chili? (Chili is a staple, much-loved ingredient in Bhutanese cuisine.)

One of the things I most enjoyed about the TBT is that it connects communities rather than circumvent them as many hiking routes do. My experience was far richer for the people I met, the homes I was welcomed into for lunch or to sleep, and the villages and towns we walked through. After all, that’s why these trails were trodden into existence over hundreds of years — to connect people. They say you should take the road less traveled, but in this case, taking the paths most traveled was a wise choice, too.

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.