Hey, Newscasters: You Should Cry More

Since the coronavirus pandemic first began, news anchors have been much more vulnerable on the air.

During a Today show broadcast on March 27, Hoda Kotb became choked up and started to cry after speaking to New Orleans Saints quarterback Drew Brees about how the pandemic had affected his hometown, and a $5 million donation he made to relief efforts. When Hoda couldn’t finish the segment, her co-anchor Savannah Guthrie kindly took over. A clip of that moment has been viewed over 2.7 million times on Twitter, and it wasn’t Brees’ name that was trending.

We love you, Hoda. ❤️ pic.twitter.com/rocZr8J4EE

— TODAY (@TODAYshow) March 27, 2020

CNN’s Erin Burnett cried interviewing a woman whose husband had died from COVID-19, and Don Lemon wiped away tears when talking about his friend and anchor Chris Cuomo’s diagnosis. In more positive news, Anderson Cooper shared that he had become a father, but expressed dismay that his own parents and brother hadn’t lived to meet his son. These moments each caused a stir across social media, and it’s easy to see why people connect so strongly to them. It’s nice to know we aren’t alone, and that the public personalities we uphold or idolize can be overcome by feelings, too. But that doesn’t mean it’s an easy needle for the on-camera talent to thread.

Maura Lewinger on CNN's @ErinBurnett is the longest but most valuable and articulate interview of someone that has lost someone to COVID-19 I've seen. Erin had a little trouble talking but I was a mess. Erin, thanks for allowing Maura to share her story for so long. #gutted

— Jerry Max Hunt (@Ryserfan) April 3, 2020

“We learn how to protect ourselves in war zones, how to sanitize your water if you are in a hurricane zone or natural disaster, how to get through a kidnapping. But, emotionally, when you are talking to people and they’re trusting you and sharing intimate details of their lives and their fears and their hopes, you carry that with you,” says Amna Nawaz, senior national correspondent and primary substitute anchor for the PBS Newshour. “The ability to put it where it belongs in the story is a challenge for journalism, but I do think there is a place for it,” she says. As a psychiatrist who’s also trained to remain neutral, I understand the desire to keep emotions out for the sake of professionalism. But I’d argue that, as Nawaz says, there is a time and place for it — and, during a pandemic, that’s the here and now.

With death rates remaining high, and some states rushing to reopen, a new likely related inflammatory illness affecting young children, and stark warnings that the virus is not going away anytime soon, emotions now seem to be as high as ever since the coronavirus arrived stateside at the end of January. Aside from scientific progress, which takes time, and clear governmental leadership and strategy on how to get and stay safe, what we need is to see that the people who share this stressful, emotion-filled, ever-changing news feel it, too. We need to feel like our emotional tidal waves, from anger to sadness and back again, are normal and validated. We need — okay, we want — to see our newscasters cry.

I love that Hoda showed her emotions! There is only so much people can take reporting this day after day. She cried for all of us 💕

— Liz Duchaney (@LDuchaney) March 27, 2020

The strong fan reactions that follow can even surprise the newscasters themselves. Amna Nawaz tells InStyle she received a lot of positive viewer mail after she reached out to touch a father’s hand at his son’s hospital bedside as he started to cry. She says, “It was just one of those moments where you wouldn’t think twice about it in real life, right? If you are sitting 3 feet away from someone and they start to cry, obviously you reach out and you put your hand on their hand or arm and try to comfort them, because you are a human being and that's what we do. I think when there's a camera there, maybe people think that the whole dynamic changes, but to me it doesn’t. I’m still a human being and I'm still talking to another human being. If that's the instinct in the moment, that's what I'm going to do.”

RELATED: Savannah Guthrie and Hoda Kotb Are Changing TV for the Better

As a psychiatrist, I understand completely the push-pull she describes between being yourself and doing your job as it’s traditionally been modeled. Like journalists, therapists are taught to remain detached and to disclose very little about ourselves, so patients can focus on themselves. That distance becomes harder to maintain when I am tired or dealing with my own difficulties. Nawaz, who says she anchored hours of 2016 election coverage on no sleep after her second child was born, agrees that, sometimes, “compartmentalization is key.”

She tells InStyle, “You cannot let your emotions get in the way of the reporting. You just learn to hold it in and power through until you are in a place where you can process it. You figure out a way because you have to, because you cannot let it get in the way of the work.”

Jamie Yuccas, national correspondent for CBS News based on the West Coast, adds that focusing on the task at hand when you cover tragedy often allows you to minimize your own troubles. “At the Pulse nightclub shooting, it was like, ‘How can I be upset that I am getting divorced? All of these people now don’t have their loved ones coming home.’ My stuff doesn’t matter,” she says.

But whether journalist or therapist, exposing oneself to trauma after trauma can take its toll. “So much of our job is diving into the dark stuff,” Nawaz says. And compartmentalizing is even more difficult when you are not just a passive observer reporting on the facts but a person who is experiencing the same tragedy in real time. In therapy, we call it counter-transference, when, for example, a patient’s story reminds me of my own experience. In the news, it’s when you are living through part of the story you're having to tell. According to Nawaz, “Now we are all covering this pandemic as we are living through it, and I don't think it’s at all unreasonable to see it start to spill over into our work, to see people get emotional about the things that they are covering.”

RELATED: We Are All at Risk of Developing PTSD From the Coronavirus Pandemic

Not only is it reasonable for the emotional impact of these events to read onscreen, it would feel disingenuous and cold to viewers if newscasters were able to turn off that part of experiencing reality; it might even feel isolating to viewers who aren’t able to simply rise above the fear and sadness they feel right now. Yuccas, whose very first day of work as an intern at a TV news station in Minneapolis was September 11, 2001, tells InStyle, that tragedy "hit New York, and it changed the way of life for so many Americans, but this virus is everywhere, you can’t escape it.”

Nawaz landed her first job just a month before in August 2001, so her career was also born of that crisis. “Journalists are just like everyone else, we have spouses, and we have kids, and we have older parents we are worried about, and we have friends that we have lost in this pandemic,” she says. Seeing your loved ones suffer, or feel afraid, heightens the emotional reality of any story, Yuccas adds. “Of course that’s going to show up when you are interviewing someone.”

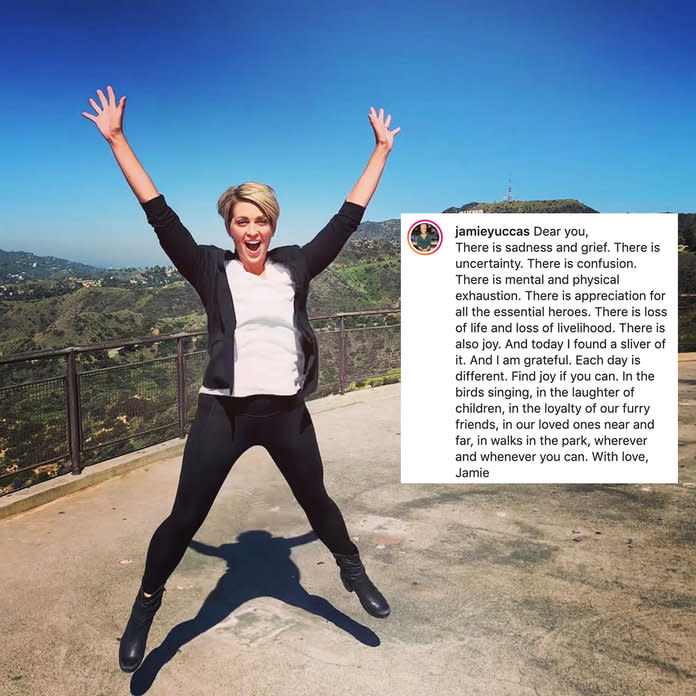

A post shared by Jamie Yuccas (@jamieyuccas) on Apr 16, 2020 at 9:47pm PDT

RELATED: Newscasters Are Doing Their Own Makeup for TV Since Glam Squads Aren't "Essential"

“Vulnerability takes strength — you have to be willing to put yourself out there. As much as you are trying to report the truth, you are trying to bring … your whole self to the job,” Nawaz says. For me, I want my anchors to be just like I want my own therapist: human, honest, feeling.

As we look toward the post-COVID-19 future, I can only hope that this pandemic will lead to a shift in what we want, expect, and even get from the news. I want to continue to see newscasters we can connect to as real. I want emotions to be seen as a strength, and for others to open up after the anchors set this new norm. Yuccas adds, “I think the silver lining to this will be when we get out of this that we are better about sharing and being kind and loving and supporting each other in whatever we are feeling. That is the hope right?” It certainly is one of mine.

Dr. Jessi Gold is an assistant professor of psychiatry at Washington University in St. Louis. Find her on Twitter at @DrJessiGold.