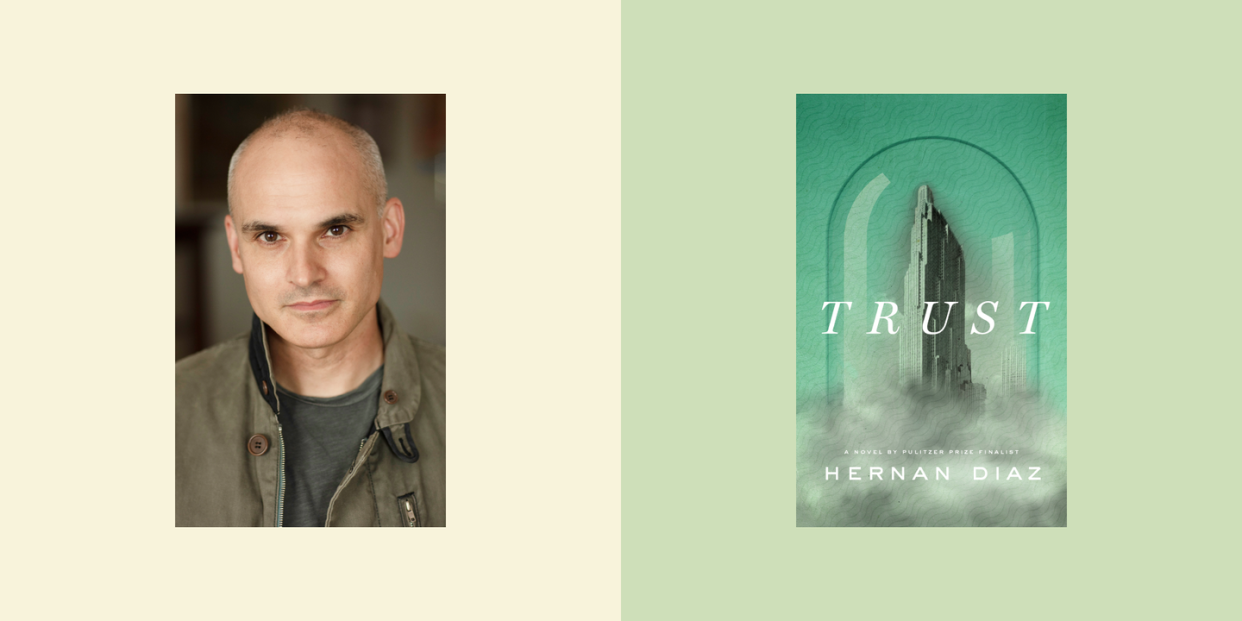

Hernan Diaz’s “Trust” Is a Literary Tour de Force

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

F. Scott Fitzgerald was dead wrong when he quipped that there are no second acts in American lives; as Hernan Diaz probes in Trust, his enthralling tour de force, there are at least four wildly disparate perspectives on the rich and infamous. He transports readers back to the Roaring Twenties and subsequent Depression, when our collective labors bore rotten fruit, seeding disparities that are still with us. He structures Trust around a childless, affluent Manhattan couple, Andrew and Mildred Bevel, in a quartet of narratives that open up like Matryoshka dolls: a novel, a partial memoir, a memoir of that memoir, and a journal. Each story talks to the others, and the conversation is both combative and revelatory. Free markets are never free, as he suggests; our desire to punish often trumps our generous impulses. As an American epic, Trust gives The Great Gatsby a run for its money.

Published in 2017, Diaz’s debut, In the Distance, was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize and the PEN/Faulkner Award. Trust fulfills that book’s promise, and then some. A finance titan in the early 20th century, Bevel has built spectacularly on fortunes amassed by his forebears. His biography is loosely re-created as fiction in Trust’s first act, “Bonds,” a thinly veiled novel written by one Harold Vanner, a hanger-on who chronicles the myth of Benjamin and Helen Rask, also a childless, affluent Manhattan couple: their opulent Fifth Avenue mansion, the shady deals that buoy them through the 1929 crash, and Helen’s fatal illness, which ends tragically in a Swiss sanatorium. Diaz’s ventriloquism here is stellar: As Venner, he channels Edith Wharton in an arch yet irresistible voice.

“And so it was that Helen, after each sleepless night spent talking to silent snooded nurses, was taken out into the garden with the first light and left alone on a chaise facing the mountains. She continued with her soliloquy while freeing herself from under the tightly tucked blankets. As the sun rose, however, her monologue declined into sporadic mutterings, which, in turn, melted in silence. For an hour or so, she would enjoy the bliss of impersonality—of becoming pure perception, of existing only as that which saw the mountaintop, heard the bell, smelled the air.”

Wordplay is Trust’s currency: The title refers not only to financial trusts but also the trust we place in each other, the contract between reader and author. As Vanner writes of Rask, “He created a trust meant exclusively for the working man. A small amount, the few hundred dollars in a modest savings account, was enough to get started.… A schoolteacher or farmer could then settle her or his debt in comfortable monthly payments.” But the social bonds in “Bonds” fray like a tattered rug. Just before the crash, Rask, sensing catastrophe, opts to make a buck at the expense of those at the bottom of the economic ladder: “He even divested from all his trusts, including the one he had designed for the working man.”

In Trust’s second section, Bevel speaks for himself. Incensed by the publication of “Bonds” in 1938, following the death of his beloved Mildred, he’s determined to set the record straight. “My Life” is an incomplete memoir, but it defiantly affirms the WASP aristocracy as Bevel recalls the past generations of his family—their genius for business, their Hudson Valley estates and European sojourns. He leaves gaps in each chapter, where Diaz romps playfully, allowing the reader to glimpse another story nestled among white space. The Wall Street tycoon may bristle at an arriviste like Vanner, but each wave of the super-rich seeks to displace the established order, as Bevel’s note to himself indicates: “More details on transaction and personal meaning of taking over Vanderbilt house.”

Bevel casts himself in the best possible light, but Diaz gleefully exposes him as a priggish narcissist, a Jazz Age Koch brother. The entry titled “Apprenticeship” is left blank—he likes to present himself as a hard-working self-made man, a prodigy, when in fact he's inherited his fortune . He jots down terse fragments as placeholders in his manuscript: “Panic as an opportunity for forging new relationships” and “Short, dignified account of Mildred’s rapid deterioration.” Sometimes he breaks off mid-sentence.

Trust’s tricks propel the novel’s third section, told by Ida Partenza, an elderly literary journalist who, in her own memoir, reflects on the genesis of her career, when Bevel hired her as a secretary to shape his manuscript. She’s kept the secrets of her employment through the decades. In the 1980s, she learns that Andrew and Mildred’s personal papers have been archived in their former Upper East Side mansion, now a Frick-like museum. Her curiosity gets the better of her: Do their narratives differ from hers? Today Brooklyn’s Carroll Gardens neighborhood may be a gentrified, sought-after address, but in 1938 it was a working-class Italian enclave, bustling with bars and butcher shops, sailors and typesetters, like Ida’s immigrant father, a Marxist who shakes his fist at the Manhattan skyline across the East River. Her visit to the Bevel museum ushers us back into an America mired in economic woes, with World War II on the horizon.

During her time with Bevel, rendered in flashback, Ida marvels at the financier’s arrogance and self-delusion: “It was also of great importance to him to show the many ways in which his investments had always accompanied and indeed promoted the country’s growth.… While geared toward profit, his actions had invariably had the nation’s best interest at heart. Business was a form of patriotism.” Although Ida is from the wrong borough, Bevel respects her talent and candor. The mysteries mount as she recounts her boss’s lies; he’s borrowed a few details from her life to flesh out his own. For her, the act of memory is a vendetta.

In Diaz’s accomplished hands we circle ever closer to the black hole at the core of Trust. Mildred’s journal, “Futures,” squeezes the gravity from what’s come before, a dizzying crescendo and the novel’s most intimate section. Mildred doesn’t have a future, but she’s very keen on recording the past and present. Bevel is capable of tenderness, as when he organizes a surprise picnic for his spouse—“overstaffed + overfurnished,” she notes wryly. “He was uncomfortable. Kept looking at the sun filtering through the twiggery as if affronted by it. Smacking non-existent bugs on his face. But kindly looked after me.”

Which narrator do we trust? One or more, all, none?

Diaz owes debts to a range of influences, from Woolf and Wharton to thinkers such as Marx and Milton Friedman. Trust is a glorious novel about empires and erasures, husbands and wives, staggering fortunes and unspeakable misery. It’s also a window onto Diaz’s method. Ida recalls the detective fiction she adored in her youth, by Agatha Christie and Dorothy Sayers: “These women showed me I did not have to conform to the stereotypical notions of the feminine world.… They showed me that there was no reward in being reliable or obedient: The reader’s expectations and demands were there to be intentionally confounded and subverted.”

He spins a larger parable, then, plumbing sex and power, causation and complicity. Mostly, though, Trust is a literary page-turner, with a wealth of puns and elegant prose, fun as hell to read. Or as Mildred writes in her journal, “a song played in reverse and on its head.”

You Might Also Like