Can Hepatitis B Cause Kidney Disease?

Medically reviewed by Matthew Wosnitzer, MD

Medical experts widely accept that one of the most misleading disease nomenclatures out there is for hepatitis B and hepatitis C-related liver disease. The titles are somewhat insufficient to describe these diseases, since the term "hepatitis" implies inflammation of the liver. This gives the impression that the only organ affected in hepatitis B or C is the liver, which is misleading—both of these diseases see an involvement of organs other than the liver, and are therefore bona fide systemic (and not local) disease states.

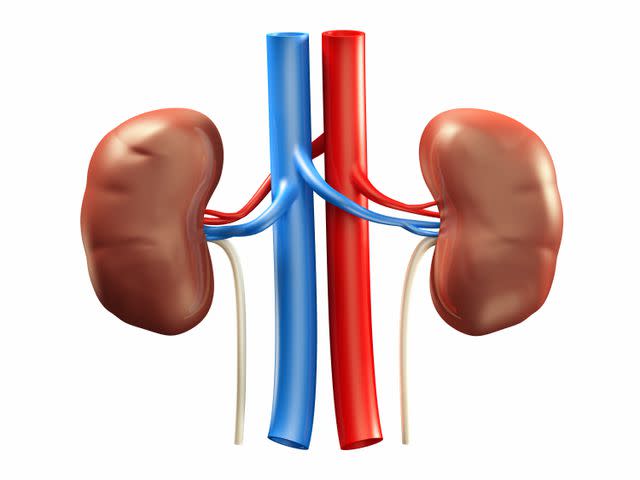

The kidney is one such organ that hepatitis viruses affect both directly and indirectly. Hepatitis viruses are not the only infectious agents that can affect the kidney. However, their role in kidney disease is important to note given the relatively higher prevalence of these viral infections. Let's discuss some details regarding hepatitis B virus-related kidney disease.

How Common Is the Association of Kidney Disease With Hepatitis B?

Kidney disease due to hepatitis B virus infection is seen far more frequently in people infected with the virus either during infancy or childhood. These patients are more likely to become "carriers" and carry a higher risk of kidney disease.

Why a Liver Virus Would Damage the Kidney

Damage to the kidney from hepatitis B virus is not usually a result of direct infection. In fact, the immune system's abnormal reaction to certain parts of the virus may play a larger role in disease causation.

These viral components will typically get attacked by your antibodies in an attempt to fight the infection. Once this happens, the antibodies will bind with the virus, and the resultant debris will get deposited in the kidney. It can then set off an inflammatory reaction, which could cause kidney damage. Hence, rather than the virus directly affecting the kidney, it is your body's response to it that determines the nature and extent of kidney injury.

Types of Kidney Disease Induced by Hepatitis B Virus Infections

Depending on how the kidney reacts to the virus and the inflammation cascade noted above, different kidney disease states can result. Here is a quick overview.

Polyarteritis Nodosa (PAN)

Let's break this name into smaller, digestible parts. The term "poly" implies multiple, and "arteritis" refers to inflammation of the arteries/blood vessels. The latter is often referred to as vasculitis as well. Since every organ in the body has blood vessels (and the kidney has a rich vasculature), polyarteritis nodosa (PAN) is a severe inflammation of the blood vessels (in this case, the kidneys' arteries), which affects the small and medium-sized blood vessels of the organ.

The appearance of PAN inflammation is very typical. It is one of the earlier kidney disease states that can be triggered by hepatitis B infection. It tends to affect middle-aged and older adults. The affected patient will typically complain of nonspecific symptoms such as weakness, fatigue, and joint pains. However, certain skin lesions can be noted as well. Tests for kidney function will show abnormalities but will not necessarily confirm the disease, and a kidney biopsy will usually be necessary.

Membranoproliferative Glomerulonephritis (MPGN)

This mouthful-of-a-disease term refers to an excess of inflammatory cells and certain kinds of tissue (basement membrane, in this case) in the kidney. Again, this is an inflammatory reaction rather than direct viral infection. If you have hepatitis B virus infection and start to see blood in the urine, this is something that needs to be considered. Obviously, the presence of blood in the urine will not be enough to confirm the diagnosis even if you have hepatitis B virus infection. Hence, further tests, including a kidney biopsy, would be necessary.

Membranous Nephropathy

A change in a part of the kidney filter (called the glomerular basement membrane) leads to this. The affected patients will begin to spill out an abnormally high amount of protein in the urine. As a patient, you may not be aware of the presence of protein in the urine unless it's extremely high (in which case, you could expect to see foam or suds in the urine). Blood is a rarer finding in the urine in this case but could be seen as well. Again, blood and urine tests for kidney function will show abnormalities, but to confirm the disease, a kidney biopsy will be required.

Hepatorenal Syndrome

An extreme form of kidney disease that results from preexisting liver disease is something called hepatorenal syndrome. However, this condition is not necessarily specific to hepatitis B-related liver disease and can be seen in many kinds of advanced liver disease states in which the kidneys are affected.

Diagnosis

If you have hepatitis B virus infection and are worried that your kidneys could be affected, you can get tested.

Obviously, the first step is to make sure that you do have hepatitis B virus infection, for which there is a different battery of tests that don't necessarily need a kidney biopsy. If you come from an area that is known to have high rates of hepatitis B virus infection (endemic area), or have risk factors for hepatitis B virus infection (such as sharing needles for IV drug abuse or having unprotected sex with multiple sexual partners), certain telltale blood tests that look for different "parts" of the hepatitis B virus should be able to confirm infection.

Testing is also done for the antibodies that the body makes against the hepatitis B virus. Examples of these tests include anti-HBc and anti-HBs. However, these tests might not always be able to differentiate between active infection (where the virus is quickly replicating), or a carrier state (where, while you do have the infection, the virus is essentially dormant). To confirm that, testing for the hepatitis B virus DNA is recommended.

Because the two viruses happen to share certain risk factors, concurrent testing for hepatitis C virus infection might not be a bad idea.

The next step is to confirm the presence of kidney disease with urine or blood tests, such as:

Dipstick urine test: This is a rapid test that looks for albumin, a protein produced by your liver. Abnormal levels could indicate the possibility of kidney disease, but more testing is needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (UACR): This urine test compares your albumin levels to your creatinine levels. Creatinine is a waste product normally present in your urine. An abnormal test result could point to kidney disease.

Serum creatinine: This is a blood test that looks for the amount of creatinine in your blood. If your levels are too high, it could mean your kidneys are not functioning normally.

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR): This test measures how efficiently your kidneys are removing waste products and extra fluid from your blood.

Blood urea nitrogen (BUN): This test measures the urea nitrogen levels in your blood. Too much of this waste product in your blood could mean your kidneys aren't working as well as they should.

Finally, your physician will need to put two and two together. After the above two steps have been done, you still need to prove causality. Hence, a kidney biopsy will be necessary to confirm that kidney disease is indeed a result of hepatitis B virus, as well as the specific type of kidney disease. It is also because just having hepatitis B virus infection along with kidney disease doesn't necessarily prove that the infection is leading to kidney damage. One could have hepatitis B virus infection and have blood protein in the urine for an entirely different reason (think a diabetic patient with a kidney stone).

Confirmation of final diagnosis and its cause has a huge impact on treatment plan as well. The disease states described above (PAN, MPGN, etc.) can be seen in people who do not have any hepatitis B virus infection. How we treat these kidney disease states in those situations will be entirely different from how they are treated when caused by hepatitis B virus.

In fact, many treatments (like cyclophosphamide or steroids) that are used for the treatment of non-hepatitis B-related MPGN or membranous nephropathy could do more harm than good if given to a patient with hepatitis B virus. It is because these treatments are designed to suppress the immune system, which is something the body needs to fight against hepatitis B infection. Treatment with immunosuppressants in this situation could backfire and cause an increase in viral replication. Therefore, proving the cause is essential.

Treatment

Treat the cause—that is essentially the crux of treatment. Unfortunately, no major randomized trials are available to guide treatment for kidney disease that happens because of hepatitis B virus infection. Whatever data we have from smaller observational studies support the use of antiviral therapy directed against hepatitis B infection as the linchpin of the treatment.

Antiviral Therapy

This includes medications like interferon alpha (which suppresses multiplication of hepatitis B virus and "modulates" the immune response to the infection), and other agents such as lamivudine or entecavir (these medications inhibit multiplication of the virus as well). There are finer nuances to treatment as far as the choice of agent used (further dependent on other factors like age, whether the patient has cirrhosis or not, the extent of the kidney damage, etc.). Which medication is chosen will also determine how long treatment can be continued. These discussions should be something that your physician will discuss with you before initiating treatment.

Immunosuppressive Agents

These include medications like steroids or other cytotoxic medications such as cyclophosphamide. While these might be used in the "garden-variety" kidney disease states of MPGN or membranous nephropathy, their use typically is not recommended when these disease entities are caused by hepatitis B virus (given the risk of flaring up the infection). However, this is not a "blanket ban." There are specific indications when these agents might still need to be considered even in the setting of hepatitis B virus. One such exception is a severe kind of inflammation that affects the kidneys' filter (called rapidly progressive glomerulonephritis). In that situation, immunosuppressive medications are usually combined with something called plasmapheresis (a process of cleansing the blood of antibodies).

Read the original article on Verywell Health.