Henderson began compacting its trash 75 years ago

Garbage is a smelly subject most people would rather not think about.

But if someone didn’t think about it – and others with strong backs follow through on that thinking – we’d soon be up to our hips in our own waste. Not a pleasant thought.

Up until 1903 local government paid little attention to garbage, except to take action when the main disposal system − better known as hogs − began breaking down fences and rooting through gardens. Other popular ways to get rid of trash included throwing it down the riverbank or an old well. Portions of the riverfront were spotted with dumps up until the 1970s.

By the spring of 1902, however, the Henderson City Council started thinking about finding a better way. An ordinance wasn’t passed until Sept. 2 and didn’t go into effect until Jan. 1, 1903. It required residents to dispose of garbage in receptacles that an able-bodied man could handle and put them in an easily accessible place.

The city scavenger took responsibility for collection and disposal. Yes, that was the actual name of the contracted position. The city hired about a half-dozen of them between 1903 and 1919 but none of them made a success of it.

Part of the problem was getting city residents to comply with the ordinance requiring easily accessible garbage cans.

“I wouldn’t have one-third of the work to do if that is done,” James R. Hall complained at the beginning of 1911.

W.H. Soaper was the city’s last scavenger, and he complained of the same problem. On Jan. 7, 1919, he submitted his resignation to the city council, which decided contracted trash collection was prompting too many complaints and should be done directly by the street department.

The council was unanimous in making the change and put up $6,500 to buy two GMC trucks “of the latest design with automatic hoist,” according to The Gleaner of Jan. 8, 1919.

A decade later, however, the city’s scavenger operation had devolved to three men with mule-drawn carts, according to a May 4, 1930, Gleaner article that unapologetically used the “N” word in its headline. The article supposedly was a conversation between two unnamed citizens in front of the post office.

“If these colored men, Sam Fisher, Will Cleveland and Julius McBride, were not efficient and particular about their work … the sanitation we harp about so much would be shot all to pieces…

“Take these colored fellows, their long-eared friends and their carts out of commission and you would soon have such an odor in the air” that the entire town would be up in arms.

The city of Henderson was unable to purchase trucks for the operation until World War II ended, at which time it bought several. By the beginning of 1948 the scavenger department had 10 trucks and employed 30 men. But that was soon to change.

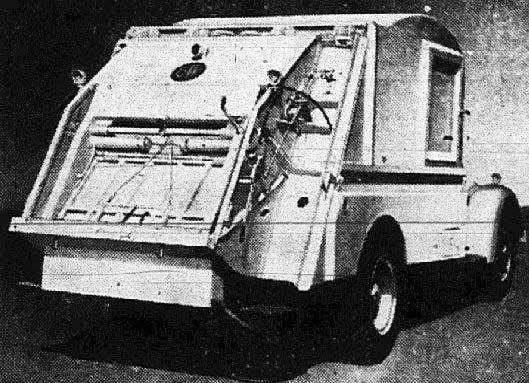

The Henderson City Commission’s minutes of June 1, 1948, show the city agreed to buy three 2-ton Chevrolet trucks equipped with Garwood Loadpacker compaction units. Argabrite Chevrolet’s bid was $17,279 – but that wasn’t what the city paid.

The Gleaner didn’t get around to publicizing the change in garbage collection until July 4. “These loadpacker units will be more efficient, they will not leak, and garbage will not be blown from them into the streets,” said Commissioner of Public Safety T.C. “Crit” Hollowell. “Each machine will be operated by three men. This will allow us to release 11 men from the scavenger department.”

The city was divided into three districts; the first truck began operating Aug. 31, the second on Sept. 1 and the third on Sept. 3.

“If the people of Henderson will cooperate with the scavenger department, we can collect garbage three times a week instead of once a week or in some cases once in two weeks,” Hollowell said.

The city commission minutes of Sept. 7 authorized the sale of eight of the 10 old trucks. It also provided for the labor savings realized by decreasing the workforce from 20 to nine be paid to Argabrite Chevrolet as the money accumulated. The annual savings were expected to be $10,000 to $12,000. The total amount to be paid to Argabrite was $18,054.

Within a week of full implementation of the new system, however, complaints started coming in, according to the Sept. 10 Gleaner. Hollowell said that was because the downsized garbage crew was still getting used to the new system – as were the citizens of Henderson.

“Certainly (citizens) have had enough notice,” county health officer Dr. Logan M. Weaver said. “We’ve had notices in the newspaper and passed out handbills but still the scavenger department is finding garbage not in containers and in places not easy to get to.”

Weaver made more pointed remarks in a letter to the editor that appeared Sept. 26. “The proper collection and disposition of garbage … is not being done to the satisfaction of anyone.”

He estimated Henderson collected from approximately 4,400 addresses, yet “more than 50 percent of our population is not yet complying with the city garbage ordinance by not putting their garbage in regulation tight-covered cans, and their trash in suitable containers easily accessible to the scavengers.”

Mayor Robert B. Posey noted in The Gleaner of Nov. 11 “he had received numerous complaints of inadequate service.” Hollowell said he hoped to have the situation corrected by the end of the week. It was not to be, however.

A letter to the editor appeared Dec. 4 over the signature of Ima Waitin. That perhaps was a relative − or even the same person − as Ima Watchin, which was a pseudonym often used by Gleaner publisher Leigh Harris.

“I have seen a white, ghostlike monster every three weeks. They say it is a garbage truck… I am wondering if we citizens might expect this thing to get our garbage and relieve us of the weekly trip to the city dump?”Complaints continued through at least mid-1949, when a letter to the editor from N.E. Brown appeared in the June 19 Gleaner.

“The garbage in our neighborhood hasn’t been emptied for two weeks. All of us have good, covered garbage cans, but that doesn’t keep out ants or odors, both of which are awful... Help with our garbage!!”

Garbage collection was funded by property taxes at that time, but the city began having financial problems in 1952. Stories in The Gleaner in February and June proposed imposing a weekly 20-cent collection fee for the first time.

"We've been getting things free so long around here that we want the city to pay for everything," said Commissioner George L. Pearce. "It can't last much longer."

It lasted until May 8, 1968, however, when a monthly $1.50 garbage fee was approved on final reading. It was levied with the water bills. The monthly fee for residential pickup is currently $20.

The city began distributing 96-gallon wheeled bins this year in July and after a month grace period began requiring all residents to use them − which has prompted some complaints. A similar proposal in October 1978 was killed by a spirited public outcry, according to articles in The Gleaner.

100 YEARS AGO

The Hockenburg System Inc. was getting ready to send two men to Henderson to begin laying the financial underpinnings for what opened as the Soaper Hotel in December 1924, according to The Gleaner of Sept. 9, 1923.

The hotel was built by local subscription of stock, which avoided the issuance of bonds. It is named for Richard Henderson Soaper because he bought the largest portion of stock.

50 YEARS AGO

Henderson County’s green box system of rural garbage collection was fully implemented the first week of September 1973, according to The Gleaner of Sept. 1. It was one of Kentucky’s first rural garbage disposal systems and was paid for with the county’s first allocation of federal revenue sharing funds.

About 20 of the county’s 50 boxes had already been placed in Magisterial Districts 2 and 3 and District 1 was to get its share before Sept. 8.

Green boxes proved to be a constant headache for county authorities, however. In early January 2004 Henderson Fiscal Court passed a pair of ordinances abolishing them and setting up a system of franchised private haulers. The last of them were gone by March 15, 2004.

25 YEARS AGO

More than 100 people turned out to speak with consultants the city of Henderson had hired to plan redevelopment of the riverfront, The Gleaner of Sept. 10, 1998, reported.

“The spectrum goes from ‘Do absolutely nothing’ to commercializing every square foot of the riverfront,” said Walt Dear, chairman of the Riverfront Improvement Committee. Compromises would be found, however, he said. “We think we can learn from each other.”

Readers of The Gleaner can reach Frank Boyett at YesNews42@yahoo.com, on the social media platform formerly known as Twitter at @BoyettFrank and on Threads at @frankalanks.

This article originally appeared on Evansville Courier & Press: Henderson began compacting its trash 75 years ago