How Hemingway Quarantined (Hint: It Was with his Wife, his Mistress, his Son and the Nanny)

Last week, a letter supposedly written by F. Scott Fitzgerald—quarantined due to the Spanish Flu in 1920—made the social media rounds. In it, Fitzgerald states that he and Zelda had fully stocked their bar, and called Hemingway a flu “denier” who refused to wash his hands. This letter went viral.

The only problem? It was not written by Fitzgerald; its true author is Nick Farriella, who had written it as a parody for McSweeney’s earlier this month. However, for those of you who crave an actual Lost Generation quarantine story, you’re in luck. Please allow me to entertain you with the true story of how Ernest Hemingway was once quarantined not only with his wife and sick toddler, but also his mistress. He actually took quite nicely to it.

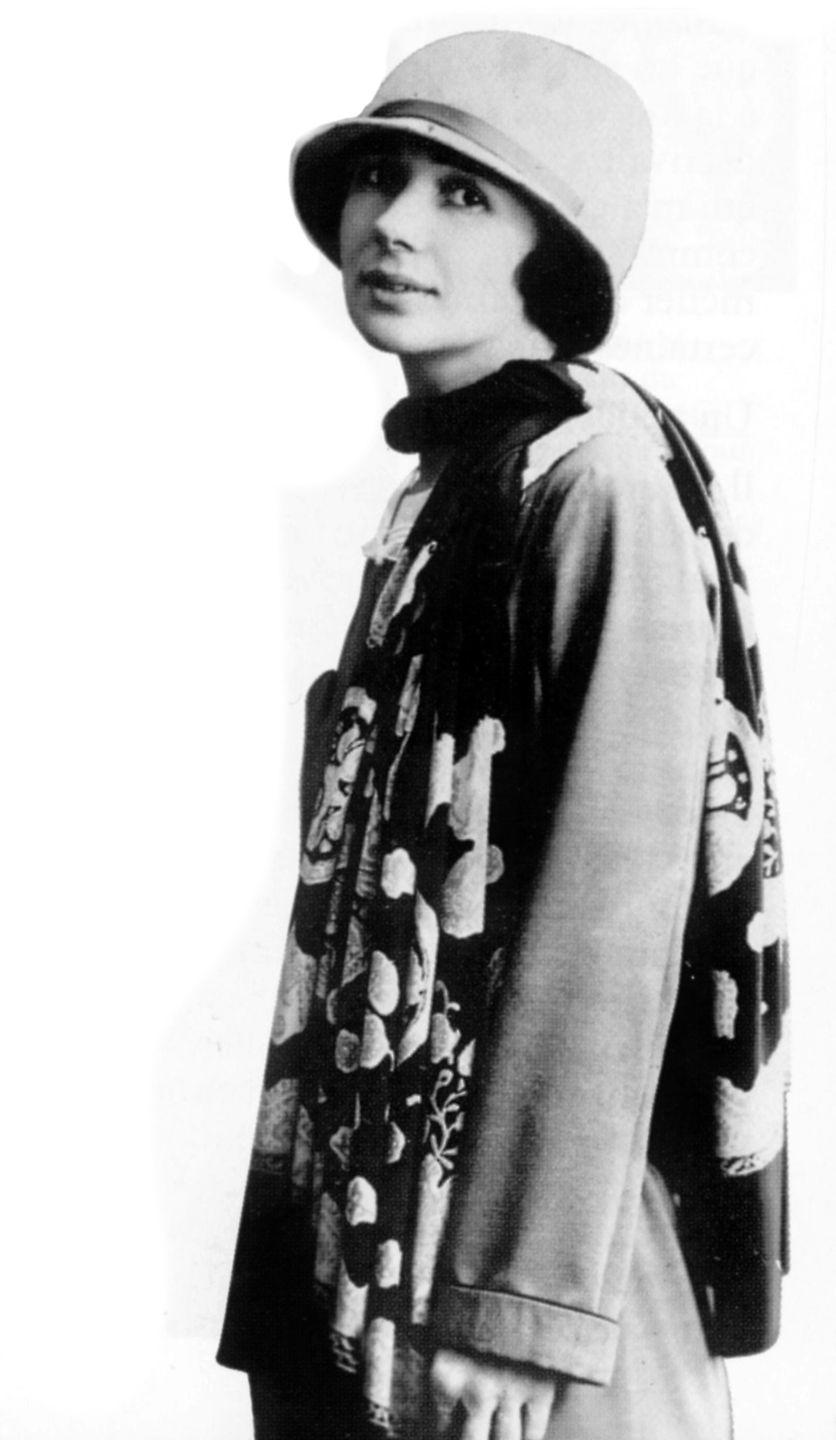

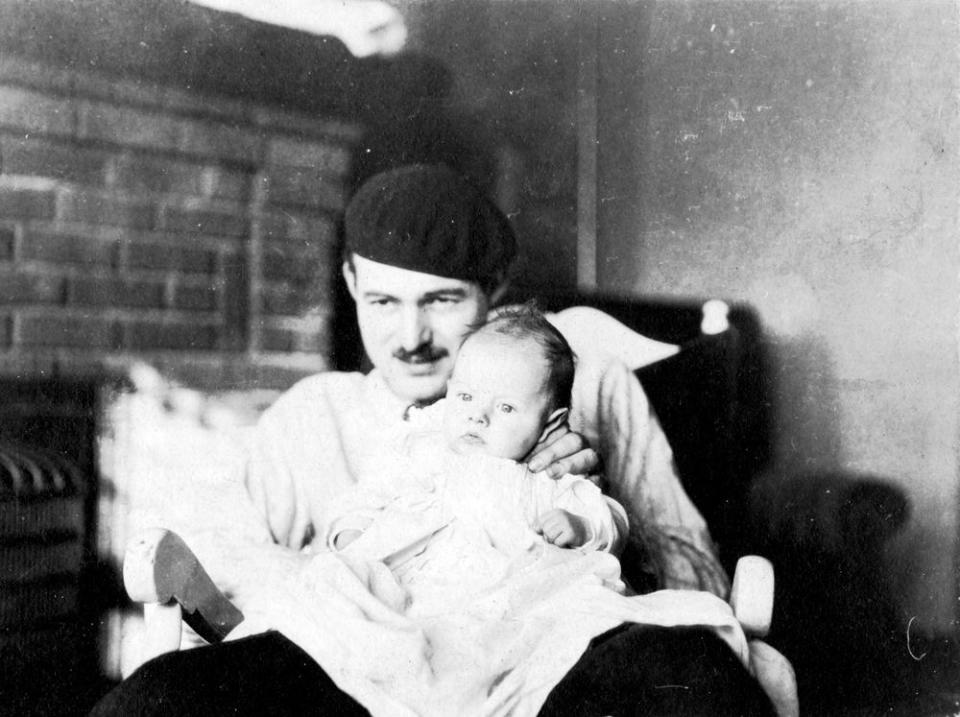

In the summer of 1926, Hemingway was still married to his first wife, Hadley Hemingway, and they had a three-year-old son Jack, whom they called Bumby. Hemingway and Hadley had arrived in Paris a few years earlier so Hemingway could pursue his dream of becoming a world-famous, groundbreaking writer. That summer he was on the brink of a breakthrough, accumulating the lifestyle trappings he felt a celebrity author must have—including a fashionable mistress, Pauline Pfeiffer.

Whereas Hadley was church-mouse–poor, Pauline was an heiress; while Hadley was homely and docile, Pauline was a sleek Vogue editor with a commanding personality. When Hadley had, just weeks earlier, learned of the affair and confronted Hemingway about it, he had grown furious and told her that she was the true offender. He raged that everything would have been just fine if she hadn’t dragged the situation into the open.

The couple decided to carry on, but it became clear that Hemingway had no intention of giving up Pauline; nor did his mistress intend to bow out. Rather, she made herself omnipresent. It was just going to take Hadley a while to get used to her new normal.

Hemingway went on to Madrid to attend the bullfights, and Hadley took Bumby to Cap d’Antibes to stay with their wealthy friends Sara and Gerald Murphy in the now-legendary Villa America. The home was a Riviera paradise, perched on top of terraced lawns and orchards above the Mediterranean.

Bumby had a cough when he arrived from Paris; it worsened when he and Hadley arrived in Cap d’Antibes. Watching the little boy play with their three children on the beach, the Murphys grew anxious and summoned their doctor, who came to Villa America to examine Bumby. His diagnosis: whooping cough, a highly contagious respiratory illness that induces violent, uncontrollable coughing fits.

On medical orders, the Murphys immediately exiled Hadley and Bumby from Villa America. Luckily, F. Scott Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda—who were also summering in Antibes—had a lease on a small house nearby and offered it as a quarantine shelter to them. Gerald Murphy wrote to Hemingway in Madrid, trying to put a good face on the situation: Hadley would probably be far happier not having to listen to the shrieks of so many kids, he contended, and Bumby was under the care of a superlative English doctor and eating fresh vegetables from the garden. Hemingway was not to worry; everything was under control.

Bumby’s nanny hustled down from Paris to the Riviera where she, Hadley, and Bumby settled into an isolated sickroom routine. The Murphys and Fitzgeralds kept “a grand distance from us poisonous ones,” Hadley reported to Hemingway, although both families sent them provisions. Loneliness and uncertainty tormented Hadley, although a walk into town and a shot of whisky helped alleviate her unhappiness and stress.

Soon, however, company arrived that made Hadley long for solitude again. “Pfeiffer is stopping off here Wednesday,” Hadley informed Hemingway in a letter.

Hadley later stated that she was bemused by Pfeiffer’s sudden appearance, even claiming to one biographer that Hemingway had likely implored Pfeiffer—who’d had whooping cough as a child and was immune—to go to Hadley and help alleviate the family’s isolation. But in reality, on May 21, Hadley wrote Hemingway and told him that she’d invited Pfeiffer “to stop off here if she wants,” adding that it would be a “swell joke on tout le monde if you and Fife and I spent the summer [together]” on the Riviera. She appeared to be making light of the tricky romantic situation. In any case, Pfeiffer moved into the house.

Soon Hemingway joined them, setting the stage for what must have been one of the odder and more claustrophobic households in literary history. The idea of sharing a two-bedroom house with his mistress, an angry wife, a contagious, sick toddler, and a hovering nanny might have brought a lesser man to his knees, but Hemingway later described the setting as “a splendid place to write.”

The Murphys and the Fitzgeralds did what they could to keep up the morale at the Hemingway-Pfeiffer homestead. In the early evenings at cocktail hour, they would park their cars on the road in front of the house have a drink by the fence lining the small front yard. Hemingway, Hadley, and Pfeiffer held up their end of the party from the veranda.

They were indeed social distancing pioneers, and it gave the Fitzgeralds and Murphys front-row seats to the drama of the Hemingways’ unconventional new arrangement—their “domestic difficulties,” as Zelda put it. At the end of each evening, the group mounted their empty bottles upside down on the fence spikes. By the time the Hemingways and Pfeiffer left a few weeks later, these trophies ran the entire length of the fence.

The quarantine worked: Bumby healed, and apparently no one else fell ill. After a few weeks, the trio moved their headquarters to a nearby hotel, where they stashed Bumby and his nanny in a little house on the grounds to continue his convalescence.

Pfeiffer remained ubiquitous—“everything was done a trois,” Hadley later recalled. Even now that they were all out of strict quarantine, Pfeiffer even crawled into the Hemingways’ bed in the morning to share their breakfast. Hadley also later recalled that Pauline insisted on giving her a diving lesson that almost killed her.

After Pfeiffer went back to Paris, she peppered the Hemingways with letters, including one that brazenly stated, “I am going to get everything I want.”

Not surprisingly, the Hemingway marriage did not last the summer. They had survived whooping cough and quarantine, but the onslaught of Miss Pauline Pfeiffer proved fatal.

This story was partly adapted from Lesley Blume’s book Everybody Behaves Badly: The True Story Behind Hemingway’s Masterpiece The Sun Also Rises. Her next book, Fallout: The Hiroshima Cover-up and the Reporter Who Revealed It to the World, will be released summer 2020.

You Might Also Like