Help! I Keep Developing Intense Crushes on the Women in My Adult Theater Troupe.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This special edition is part of our Guest Prudie series, where we ask smart, thoughtful people to step in as Prudie for the day and give you advice.

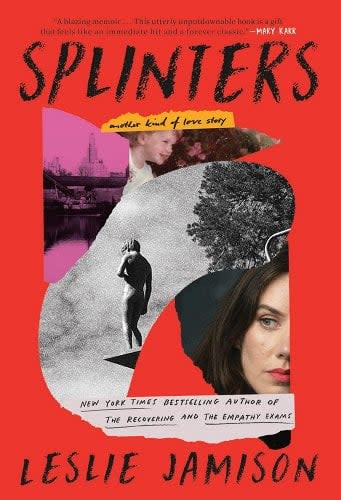

Today’s columnist is the bestselling author Leslie Jamison. She’s written New York Times bestsellers The Recovering and The Empathy Exams; the collection of essays Make It Scream, Make It Burn, a finalist for the PEN/Diamonstein-Spielvogel Award; and the novel The Gin Closet, a finalist for the Los Angeles Times Book Prize. She writes for numerous publications including The New Yorker, The Atlantic, the New York Times, Harper’s, and the New York Review of Books. Her latest memoir, Splinters: Another Kind of Love Story, hit shelves this week.

We asked Jamison to weigh in on intense crushes, competitive tennis, and stifling friendships:

Dear Prudence,

I (a married dad in my early 40s) have been part of an amateur theatrical troupe for the past decade that does a single annual performance. Last year, I developed a crush on a castmate, “Francesca”—an intense, hormones-out-of-control level crush, the likes of which I hadn’t experienced since my teen years. I didn’t act on this crush for many reasons: I didn’t want to cheat on my wife; Francesca offered no indication she felt the same way about me; and I didn’t want our troupe to get a reputation as one where married men hit on actresses. It caused me a lot of sleepless nights, but I held myself together through our final performance, said a friendly goodbye to Francesca, and never talked to her again. I told nobody, not even my closest friends.

Skip ahead to this year. Once again, I’ve developed an intense crush on a castmate, “Jeanne,” and once again, it’s causing me no end of internal turmoil. This time, I think there’s a small chance Jeanne’s interested in me, but the other barriers to making a move still apply. My marriage is in OK (not great) shape, which might be part of the issue, but my wife and I have always been faithful to each other. Why am I getting these crushes? How can I stop it? And what should I do to quell the emotional storm raging within me, at least until our performance is past?

—Flustered

Dear Flustered,

First of all, I like that you are writing to a stranger about this crush rather than acting on it, or just quietly hating yourself for it. I’m a great believer in daydreams as signal flares: not necessarily roadmaps, but information nonetheless—a sign of desire or curiosity, restlessness or estrangement. To be clear, I say this as a lifelong daydreamer, who has had so many crushes—in my teenage years, in adulthood, in marriage, post marriage—that I bring no judgment to my answer; only bone-marrow deep levels of resonance.

As the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips argues, “Any ideal, any preferred world, is a way of asking, what kind of world are we living in that makes this the solution … What would the symptom have to be for this to be the self-cure?” So, my question for you here is: What symptoms are these crushes trying to cure? This is not me saying: Why don’t you have an affair with Jeanne? I don’t think an affair is the cure. I think the crush is information. That’s the question I want to ask you, which is already a question you’re asking yourself: Why am I getting these crushes?

Looking at your letter, I was struck by the fact that so much of the focus is on the crushes—Francesca, Jeanne, the hormones, the highs, the question of reciprocity or not reciprocity, the teenage drama (and even escaping back to teenage feelings is itself a useful way out of the present, the humdrum emotional even-keel of middle-age). Then there’s this one tiny, telling parenthetical “(not great)” about your marriage, that actually feels like it might be the core of it all, the tiny knot of hair around which the larger, messier knot of hair has gathered and grown unmanageable. In a way, this is part of the design of a crush (and even an affair)—it focuses our attention elsewhere, away from the long-term familiar problem and toward something new and exotic, a dynamic that lets us feel different things and feel like an alternate version of ourselves.

What is the nature of the “not great” that is trying—I think—to break out of those parentheses and be seen more clearly? Is it just that being in a long-term relationship with kids can feel monotonous and claustrophobic and domestic and confining, even in the best scenarios? Or are the crushes, in a sense, ways of turning away from deeper issues in your relationship? That you’re not communicating that well; that you’ve lost some kind of important emotional closeness amidst the forced proximity of shared childcare and domesticity? Whether you find yourself identifying with these characterizations or not, I think your question isn’t about the crushes, it’s about the marriage.

So what if you return to the familiar problem that the novelty of these crushes offer an emotional escape from: Look more closely at your marriage, its tensions and its distances, but also what’s still good about it—don’t just build up the case against it, let yourself pay attention to what still feels connective or enlivening, whether that’s reality TV after the kids go to bed, a sense of humor you can’t share with anyone else, an urge to tell your partner hard things before you share them with anyone else… The marriage is absolutely where you need to be focusing your energy, not the crushes themselves.

I don’t think crushes are always a sign of something terribly wrong with the primary relationship. Sometimes our minds just wander in fantasy, freeing themselves from routine and familiarity by imagining other lives. Honestly, I think that’s part of being alive, imagining other ways to be alive—and it’s certainly not necessarily pathological (though it can sometimes feel shameful—as if we’re being unfaithful to our lives just by thinking about other ones). But in this case, it also seems like you are aware that there’s something else.

Practically, I’d suggest a few things: If the crush on Jeanne feels so intense and overwhelming, I’d put up some boundaries. Don’t seek out pockets of time alone with her or find excuses to chat or text. Make sure there are other people around when you talk. No need to do anything overblown or extreme, just keep the guard rails on. And really—and this is the most important part of my advice—redirect your attention from the crush back to your marriage. What can you do to investigate and change the “not great” here? Maybe that looks like getting a sitter one night a week and going on more dates? Figuring out pockets in the week when you can have more sex? Setting up a weekly time to start talking about what you’re each feeling, in your lives and with each other? Trying to regularly carve out a half hour at the end of the day to really catch up about your days? Going to couples therapy to start talking more intentionally about your dynamic and how it might be deepened, enlivened, resuscitated? (I know couples therapy gets a bad rap, but in my experience, it can actually be quite useful and clarifying.) Every marriage is a foreign country, so I’m not going to be able to say what might bring more closeness or connection in yours, but that’s the question you should be asking yourself.

Dear Prudence,

We are a (co-ed) group of elderly friends who have a regular doubles tennis game. One of our members is incredibly hard on himself—curses, throws his racquet, and desperately wants to win. He never seems to be enjoying himself, and as a result, the rest of us get frustrated with him as well. The thing is, his anger is exclusively internally directed. He never criticizes anyone else, he’s warm to everyone, asks after the grandkids, thanks everyone for playing, etc. We’ve tried to gently say, “Harold, it’s just a game!” but he shrugs it off. If he were a jerk to everyone, we might feel OK about kicking him out of the game, but he’s a nice guy, he’s just really driven. But we’re all having a lousy time playing with him. How do we handle this?

—Getting Tired of the Game

Dear Getting Tired of the Game,

What a great question! I appreciate the ways you are both honest about your frustration and also resisting the impulse to vilify Harold—appreciating that he never really directs his anger anywhere but himself, and strives to be a good friend in other ways. (Also, I’d like to get a T-shirt that says, “Harold, it’s just a game!” I feel I could use reminding of this, too.)

My advice is simple: Talk to him about it. Maybe you already have. I really think this is the only way. You can say whatever feels right, but I’d say something like, “Harold, we love playing with you. We love these games. But your frustration levels make it stressful for the rest of us. We see that you are trying not to direct your frustration at other people, but it still makes it…pretty impossible to enjoy playing with you. Is there a way you can shift your energy when you play? Or else perhaps find partners who can match your energy with their own McEnroe-style outbursts?” Maybe there’s a way he could channel this frustration into something more practical like…lessons? As someone who occasionally plays tennis and does get very frustrated when I play badly (which is always, because I’m not very good) I can say that it was actually quite useful when my partner told me, look, if you get into a bad mood every time we play, it won’t be fun for either of us. That was useful directness for me—I worked on trying to get less reactive, and enjoyed playing a lot more. (My partner also notes that he sometimes lets me win without telling me.)

I’m also aware that the simplest advice—about verbalizing something that might be difficult for someone else to hear—is often the hardest to follow; but I’m thinking of something an old recovery sponsor once told me—that I felt like I had to work out the answer to everything in my head before I spoke it aloud; when really I needed to do more to share the work of problem-solving with other people, bring them into the problems earlier, so they could help me solve them. So I say: Bring Harold into this dilemma. By speaking to him directly, you give him the chance to help you figure it out.

Dear Prudence,

I’m tired of my friends. In the past couple of years, I’ve noticed that more often than not, I can’t think of one person who is refueling or fun to be around or speak to. I dread phone calls because I know that I’ll be subjected to an hour or more of sad-sack monologuing. “Keeping up” with my friends by text feels like a chore. I know that life is hard and tragic, but I feel like all I do is try to come up with creative ways to phrase the same, “I’m so sorry, that sucks so much” refrain 10 different times throughout the day.

I’m known among my friends as a kind/loyal person and a good listener, and honestly, that’s starting to bother me. I’m also funny, acerbic, and smart and have lots of opinions on pop culture, literature, and current events—but they all fall to the wayside so I can “comfort” people over and over again about their bad relationships, depression, anxiety, chronic health issues, etc. I understand that many of these people are genuinely suffering, and I feel guilty for feeling this way behind the empathetic listening ear I present. I also get that it’s easier to update people on the “big issues” when your friends are long-distance (most of my friends are out of state). I moved to a new city two years ago and have tried relentlessly to go out and meet people, but the most I’ve succeeded in doing is collecting a handful of “activity partners” that I’m not particularly close to. Is there anyone out there who is having a good, or even just OK time? Will I ever get to talk about books or reality TV or that one weird Atlantic hot take, or am I doomed to a life of being a bottomless, trauma receptacle? For context, I have chronic fatigue and my own mental health issues. I’ve heard that “compassion fatigue” isn’t real, but this doesn’t feel sustainable. How can I keep my friends and my sanity without losing even more spoons than I already have?

—Surrounded By Eeyores

Dear Surrounded by Eeyores,

You will get to talk about books and reality TV and that one weird (well, many weird) Atlantic hot takes! I want this for you! I believe in this for you! I also believe in talking about friendship dynamics in more robust and complex ways—the kind of conversational energy we often reserve for romantic relationships—so I appreciate your question, and the chance to dig into this unsatisfying friendship micro-climate you find yourself inside of.

To me, it sounds like there are a couple of different issues at play: your dynamic in these long-term, long-distance friendships; and the question of how to make new, meaningful local friendships. Maybe these two questions are both influenced by the chronic fatigue and mental health issues you mention briefly—and, without knowing fully what you mean, I can say that in my own experience, depression has a way of coloring everything (a shrink once asked me: “Do you feel like you see everything through shit-colored glasses?” and the framing resonated). So of course I also think it’s worth doing the work of figuring out how mental health struggles are inflecting how you perceive all the relationships in your life, but I sense you already bring quite a bit of self-awareness to that work, so I’ll stick to a few thoughts on the long-term friendships and how you might shift some of these dynamics.

There’s something so powerful that can happen in any long-term close relationship: Both people get quite entrenched in their roles, often without even quite realizing it, until one (or both) people start to feel the grooves of their roles as overly small rooms without enough oxygen or wiggle-room. Here’s a story that I think connects to yours. (Spoiler alert: In this story, I play the role of one of your friends, talking endlessly about my problems until I unknowingly shut a long-term friendship into a too-small room.) Shortly after my separation, I felt one of my oldest and best friends pulling away from our dynamic—and when I finally asked her about it, she articulated that she felt a bit exhausted by our relationship. I was always going through some kind of dramatic transition (breaking up, getting sober, eloping in Vegas, getting divorced) and she was always listening to me talk about my Big Feelings about going through that dramatic transformation. The groove of that had become tiring. I can’t tell you how useful it was for me to hear this from her—because we both brought good intentions to the relationship, and both of us wanted the best possible friendship with each other. I focused more on directing our conversations toward her; and—more broadly—allowing our time with each other to feel more capacious and expansive: not just long conversations but also shows, museums, walks, concerts. Letting the world in. Opening the windows.

From what you’re saying, it seems like some of your friendship grooves have become stifling to you—that you’ve become the one who listens, who consoles, who receives the venting of others. How do you open the windows of these rooms, grant these friendships more oxygen, grant yourself the chance to occupy a different role—to be the one sharing about your own struggles, for starters, but also the chance to steer the conversations toward more enlivening terrain. I think it’s a valuable and necessary part of friendship to talk about what’s emotionally or logistically difficult (or just intense) in both peoples’ lives, but I think ideally this is reciprocal, and I also think it’s important for a relationship to have some tonal range, to contain multitudes, and I certainly think both people should get to advocate for the tones and topics and textures they want the relationship to contain.

Pragmatically, my advice for you is two-fold: First of all, as implied by all of the above, I’d suggest you talk to your friends about your dissatisfactions. You can be direct without being cruel. Just stick to what you’re feeling—that you’re always the one listening, that it can feel one-sided and overly dominated by venting and negativity. But pair this with a discussion of what you want more of: Do you want more space to talk about your own life? Do you want more space to talk about third points (books, TV, hot takes)? Maybe you could even set up something like a two- or three-person book club, or article club (I’ve done both) where you read something and then talk about it together. This sounds cheesy but is actually amazing—a way to structure the kind of outward-looking conversations it sounds like you want more of. Whether or not this sounds appealing, I think direct conversation with your friends about these friendships is the only way forward.

My second piece of advice is basically: triage. You might want to do some thinking about which relationships feel strongest—most worth investing this energy of renovation into—and which ones don’t feel like such promising candidates for this intentionality. That way, you can really focus your energy on the relationships that mean the most to you, and try to get those relationships into a more satisfying version of themselves.

But more than anything: Let your friends become part of this process of renovation—my guess is that they cherish you and absolutely don’t want you to feel this way, and want to be the best friends to you they can be. By getting honest with them about how you feel about the friendships, you give them the chance to join you in the work of transforming them.

My husband has always been very healthy, but he is now well into his 50s and is starting to develop issues. The problem is that he refuses to treat his health seriously. He doesn’t even have a general doctor, has had none of the milestone checks he should have had at his age, and will see somebody only if I make it harder not to, which I am reluctant to do.