Hell in the SRO: A Veteran's True Story

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below."

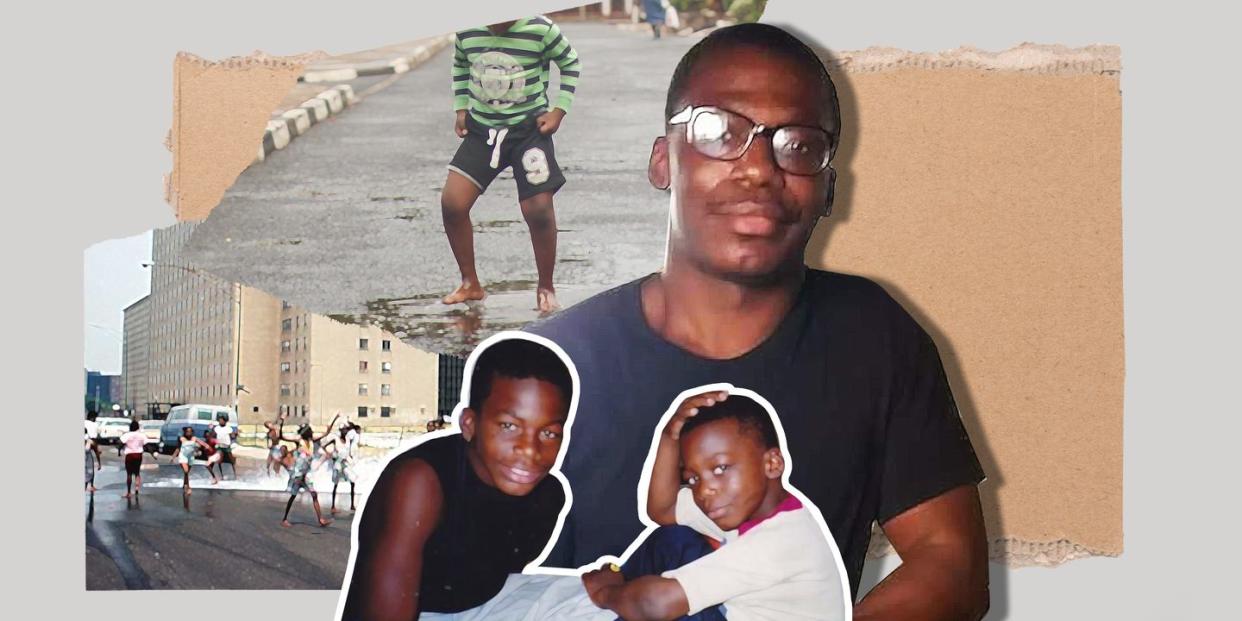

I had been unhoused for three years when the Department of Veterans Affairs finally offered me a “solution.” In the spring of 2011, they sent me to a Bronx-based single-room occupancy (SRO) where my room was the size of a prison cell. Within minutes of arriving, I knew I had to get out. Roaches skittered across the floor and walls. People struggling with all manner of addiction surrounded me, slumped over in corners, pounding their fists on the door of the resident dealer. When I stepped outside for fresh air, a white woman blew past me in a huff. She had angry, uncombed hair, a white residue plastered around her mouth, tattered shoes, and hands dirtier than a mechanic’s. In my periphery, a red Rascal mobility scooter hummed by. Its driver palmed a bottle of E&J Brandy, and his drawers slouched down around his ankles.

This was no place for a Navy veteran struggling with substance use and post-traumatic stress disorder. There, in a building teeming with addiction and violence, it dawned on me: The VA is not in the business of serving veterans like me. Those of us without housing, on the margins of society—we were the forgotten ones. I had spent the preceding winter on the streets of Brooklyn, a dangerous place to be a Black homeless veteran during the era of stop-and-frisk. I was regularly harassed by the police. Within my first month in the city, I saw cops slam at least 15 homeless vets to the ground. They’d turn vets’ pockets out at subway stations or in front of bodegas. They forced us to stand up if we sat down on the sidewalk. They called us bums and shouted threats like “I’ll bust you up if you don’t move.” I craved stability but had no support system, no mental health care, nothing to bridge the immeasurable gap. So I unraveled until the threads of my sanity came undone. I drank 40s to numb the pain. I struggled with frequent psychological breakdowns. Memories from that period still haunt me—sleeping outside in the bitter winter, hallucinating my dead mother’s head rising from a chair, and hyperventilating in a full-blown panic attack on the floor of a subway car. During this time, suicidal thoughts raced through my mind on a nightmarish loop. I almost didn’t survive it.

I was among the tens of thousands of veterans facing homelessness in America. While our numbers have declined by 50 percent since 2010, in recent years the numbers have edged up or stagnated at just under 40,000. Black veterans like me made up about a third of veterans without housing, even though we’re just 12 percent of this country’s total veterans. We fall through the cracks because the VA does little to educate us about the benefits we deserve, and when we do seek help, we’re ignored, insulted, forced through their dizzying bureaucracy, or offered subpar solutions. In my case, I was sent to a derelict SRO where I faced constant danger and could not build a stable life. I needed wraparound services that addressed the root causes of my situation. Instead I was given a Band-Aid. It would take me years to figure out the secret to getting the safe housing and other benefits I deserve.

This is the story of that journey.

The VA has a sordid history of denying benefits to a range of veterans. Millions of Black veterans of World War II were refused access to the education and housing benefits of the GI Bill, inhibiting their ability to build intergenerational wealth, while their white counterparts flourished by comparison. Today, things aren’t much better. Black veterans face more rejection and receive significantly lower benefits, according to a preliminary analysis by Yale Law School of VA data. Black veterans face higher rates of homelessness and poverty, according to the Black Veterans Project. Meanwhile, female veterans comprise the fastest-growing demographic of unsheltered veterans. Many are victims of military sexual trauma, a major risk factor for homelessness, according to the VA. But they too don’t receive the benefits they are due, often because they face mistreatment and harassment within the VA health system. The VA also actively denies benefits to veterans who did not receive an honorable or general discharge, not recognizing that many veterans charged with misconduct—like substance abuse—act out because of the trauma they experienced in the military. On top of all of this, the VA fails to recognize that housing insecurity compounds veteran trauma, stripping us of the executive functioning needed to traverse the massive administrative labyrinth we are forced into when seeking stable housing.

My upbringing did not prepare me to navigate such complex bureaucracies. I was raised by a mother who abused me. I was kept out of school until I was 11 years old. For my entire youth I only knew the violent landscape of Chicago’s housing projects. At 18 I tried to climb out of poverty by joining the Navy. My cheeks still had their baby fat when we set sail across the globe; I had no idea of the fresh trauma that awaited me. A number of my fellow sailors committed suicide after returning home. I stuck to the Navy for four years, aiding operations as an information technology specialist, fully bought into the military’s mythology that such skills would guarantee me a job in civilian life and that if I faltered, I could always lean on the VA. Instead, my roughly 50 job applications led to zero job offers. Without a stable income or mental health support, my life careened off course. I lost my apartment, my job, and my car. I tried going back to school, but a school administrator told me I didn’t qualify for the GI Bill. (I’d find out years later that this wasn’t true.) I bounced around the American South, and when I could no longer take the racism, I made the decision to go to New York for work and because a friend said he had a spare room for me. Unbeknownst to me, this was a limited-time offer. I was out on the streets weeks later when I “became a burden.”

That was January 2011, when “snowmageddon” entered the city’s lexicon. I worried about stepping on an untested square foot of snow, then plummeting to my death because it was actually an open manhole. The only items protecting me from the freezing weather were my black Levi’s jeans, a thin black jacket that held up like rice paper in a rainstorm, and white Converse shoes, stuffed with plastic bags, because that’s the only footwear I owned. In a shelter, other homeless veterans suggested I get help from the VA. After the snow thawed, they placed me in the SRO.

I tried to white-knuckle my way through living there, but stress from the frequent shootings and stabbings inside the building and around the neighborhood became unbearable within months. When the neighboring McDonald’s and check-cashing shop got shot up, it sent me over the edge. I met with my VA case manager and asked him to move me someplace safer. He made it clear that he had many other clients just like me, all of whom were in SROs. It could be worse. He didn’t have to say it, but I could read between the lines: I was just a number. But I didn’t give up. I began visiting the VA two to four times a month to ask for better housing, my requests increasingly desperate. Invariably, the receptionists spoke down to me in rude, combative tones. And my case manager repeated the same line every time: The VA was “working on it.” But nothing changed.

The one thing that did change with each visit: the interior design. The VA frequently took on projects to beautify the VA hospital in Kips Bay. A gigantic piano. Eight-foot-tall paintings and ceiling-to-floor murals of American flags, of veterans dressed in their finest military attire. Recently they’d added a wooden stage, I suppose to make announcements. Overhead screens read off the names of people in line waiting for meds. One time, after another frustrating exchange with a receptionist who refused to help me, I grew enraged. “You know what I see around here?” My voice grew louder with each word. My fists were clenched so tight my nails broke skin. “The lobby looks like a damn museum!”

It was all so beautiful but for what? The VA is chronically understaffed. The bureaucracy is maddening and time-consuming. To veterans facing chronic pain, life-altering injuries, and mental health crises, renovations are meaningless. We’d rather have a dated building if that means we get the care we need.

It wasn’t until the fall of 2012 that I learned the secret to cutting through the VA’s red tape. I was still living in the Bronx, where the daily chaos continued to push me to the brink. I was also working a minimum-wage custodial job at the Bronx VA, alongside other homeless or semi-homeless veterans. We scrubbed toilets, mopped floors, and heaved massive bags of garbage into dumpsters. One day, while eating in the cafeteria and complaining about how the work exacerbated our chronic pain from military service, we realized that we were all struggling to access our VA benefits.

“I been tryna get a upgrade on benefits for like five years,” said a lanky young veteran with close-cropped hair. “They told me ain’t enough proof that my condition is worse. I’m just tired of this stuff ’cuz I still got nightmares every night. Watched this one dude get his head knocked clean off from a IED.” His eyes were misty.

“Three a my mans kilt themselves last year waitin’ on benefits,” said another brother, Tyler, who looked like he could have been in high school. His voice was gritty but smooth—cold butter on dry toast. “We all served in Iraq. Took shrapnel. All of us in mad pain.” Tyler took a long drag on his cig, smoking it all the way to the brown of the butt.

We could all relate to the unbearable pain he described—the kind of knife-twisting agony that won’t let up. It’s fucking hell. We all knew fellow service members who killed themselves just to end their suffering. The VA has acknowledged vets commit suicide more often when they are in pain, yet they routinely under-treat or entirely fail to treat us. When I tried to see a doctor for my chronic back and knee pain, they made me wait over a month to see a doctor who simply gave me aspirin, which I already had. I needed stronger pain medication paired with physical therapy, but the VA’s history stood in my way. Opioid manufacturers have a history of having the VA promote and distribute opioids, which led to overmedication and veteran overdoses. Since mid-2012 the VA has been ordering a drastic cutback of opioids for chronic-pain patients, in order to fix the problem they created—ironically, creating more addicts who turn to harder drugs when they cannot get doc-prescribed solutions.

For veterans like me and my VA Bronx colleagues, dealing with the VA felt endlessly frustrating and futile. We were all homeless or barely housed in dangerous SROs where we had little chance of attaining stability. When we did advocate for ourselves—like I had multiple times a month—we were met with casual indifference. Glancing at each of my brothers at that table, I could see in their eyes the same exhausted despair that I saw every time I looked in the mirror. The table grew quiet. That’s when an older veteran cut in. His name was Henry, and according to him, we were doing it all wrong.

“Look here, young buck,” he said, leaning in conspiratorially. “You can’t just go in there lookin’ good. They ain’t gonna give you anything if you look like you’re okay.” He went on to explain that in order to compel the VA to help us, we had to get their attention. We had to be loud. We had to look frighteningly disheveled, like we were on the brink of killing ourselves.

“Took me 19 years ’fore I got my benefits,” he continued. “I was in Vietnam, talkin’ to myself most days. I go into the benefits office witout shavin’ and smellin’ like I took a shower in garbage—they gave me back pay the end o’ da monf. They don’t wanna give you yo’ benefits, young blood. You gotta make them.”

I thought back to all the times I harnessed my most calm, measured voice when making requests at the VA and how that simply led nowhere. Henry was right. I had been doing it wrong. His words seemed to switch on a light bulb. I felt empowered, like he just handed me a secret weapon.

The next week, I showed up to the VA, unwashed, unshaven, unashamed. I had become depressed, so it wasn’t a stretch for me to do these things. I was beginning to feel like a guy on his last day of work—I was going to take everyone down with me. The thought of killing myself had been on constant loop—in my mind, I committed suicide about ten times a day.

“I need help…now!” I screamed the words as if my life were being threatened. “I’m homicidal and suicidal, and I’m tired of ya’ll not paying attention!” I’d already reached the point of tears. The SRO had been getting more violent and drug infested. I couldn’t take it any longer.

Immediately, a VA representative greeted me. “Mr. Miller,” he said tenderly. “I think we can find someone to help you.” After about three hours speaking to psychologists, counselors, and administrators, something magical happened. It worked. Squeaky wheels were successfully oiled. Within a few days of that visit, the VA set up an appointment with an official at the VA’s office in Lower Manhattan. His face was caring and his voice gentle. A far cry from anything I’d experienced up to that point. He helped me fill out an application to receive the Post-9/11 GI Bill with a stipend for college, and within a couple months, I’d get that money and be in college. That money was enough to pay for my new apartment and full-time tuition at the New School. I soon found a fellow vet who was looking for a roommate. He was a little quirky, but so was I. I’d end up living in a duplex in Brooklyn for the next three years, forever saying goodbye to homelessness.

Even a decade later, I’m shocked by the extreme measures I had to take to force the VA to treat me with respect and give me what I was due. Afterward, life still had its challenges, but my safe housing and education gave me the foundation I needed to finally build my life on solid ground. I’ve established my career as a writer with bylines in The New York Times, Wired, and many others, dedicated to bringing attention to the VA’s misdeeds. I’ve saved money, made friends, and received treatment for my addiction and mental health struggles. This is what is possible with housing security. This is what is possible when you’re not living in a constant shudder of fear.

In the Bronx SRO, I went to bed each night to the chorus of sirens, gunshots, and people banging on the door of the drug dealer across the hall. Today, I live on my own in a clean studio apartment on a beautiful tree-lined street in the Upper East Side. The neighborhood is safe. Across the street is a park with a playground and running path. We have restaurants of every cuisine and—my favorite—a bodega where the workers know me by name.

Now I fall asleep to a different routine. Nighttime brings a hush over the streets. As I pull my curtains shut, I see light reflect off the East River and the buildings around me go dark. I run my fingers through the silky fur of my tabby, Claire, before she burrows into her cat tower. Then I lie down in the soft quiet and drift off to sleep.

This story was supported by the journalism nonprofit the Economic Hardship Reporting Project.

You Might Also Like