Want to understand the Enlightenment? Avoid this book

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Given the chance to do some touring in a time machine, I would head straight for the 17th century. Oh, for the chance to attend the first performance of King Lear, view the latest painting by Rembrandt with the oil freshly glistening on the canvas, discuss politics with Hobbes and God with Spinoza … You know that you could relate to these people, because, for all the strangeness of the times they lived in, they helped to form the mental world we all now take for granted.

Paul Strathern obviously believes this too. Several of his previous popular histories have been about Renaissance Italy (the Medici, the Borgias, and so on). But his new book moves forward from there to take in the whole of European culture from Cervantes to Dryden, from Descartes to Newton. And not just culture: commerce is included, and voyages of exploration, and wars and politics as well.

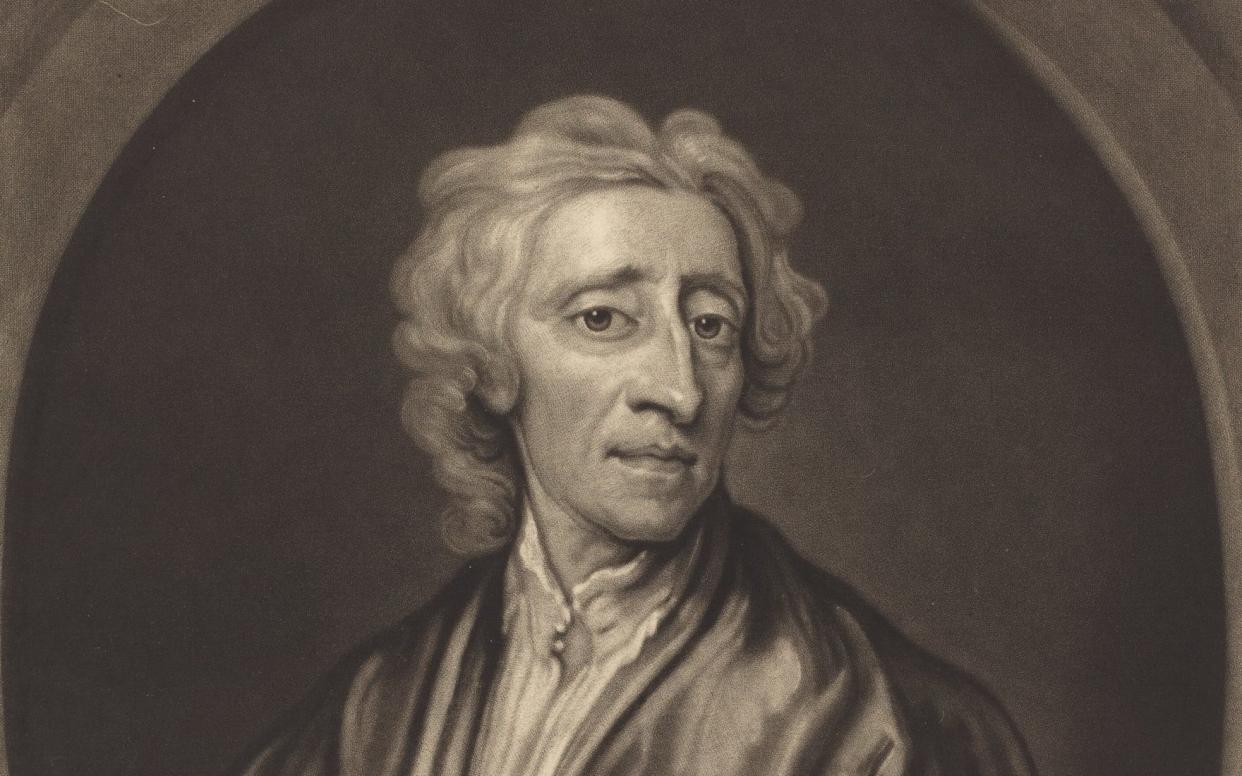

Naturally, to do all this in a book of a few hundred pages requires much corner-cutting and liberty-taking. Mostly we jump from one pen-portrait to another, with mini-lives of well-known figures such as Caravaggio, Rubens, Milton, Locke and Leibniz, plus a few less-known ones, including the Mexican writer and nun Juana de la Cruz and the German intellectual and entrepreneur Johann Becher.

Is there an overall argument that binds this assortment of human stories into a coherent whole? Yes and no. Yes, because Strathern structures the whole book around the concept of “the Age of Reason”, a description of this period which many historians are now reluctant to use. Strathern’s argument in Dark Brilliance is that the onward march of Reason was accompanied by a lot of Unreason (religious prejudice, slavery, violence, etc), and that we have to consider the deep connections between the two.

But no, because he does little to demonstrate those connections, so that his approach largely amounts to “on the one hand this, and on the other hand a bit of that”. It is a well-known cliché of guidebooks that they can describe any city as “a city of contrasts”; the same principle has just been applied to a century of European civilisation here. Nor does it help that Strathern’s idea of “unreason” is very hard to grasp: on one page it is applied both to the philosophy of John Locke, because he believed that knowledge began with sense-perception, and to the Glorious Revolution of 1688 (which strengthened parliamentary democracy), apparently because it involved inviting foreign rulers to replace the king.

I wish I could say that readers can still benefit from the mass of interesting details this book supplies. But here we come up against another problem, which is that too many of the details are unreliable. When writing about philosophers, Strathern depends most of all on Bertrand Russell’s History of Western Philosophy – a fine work in its day, but that day was in the 1940s. The main problem, however, is not with points of interpretation; it is with elementary matters of fact.

For the little-known German polymath Becher, for example, there is a good modern biography by Pamela Smith; Strathern has apparently not read it, and many of the things he says about Becher are wrong. For the well-known Thomas Hobbes, there are more sources of information than John Aubrey (the 17th-century author of Brief Lives), Russell and a couple of encyclopaedia articles. It is not true that he lived abroad from 1630 until 1637, did no scientific experiments, or is buried close to Chatsworth (rather than Hardwick Hall).

The Thirty Years’ War did not extend throughout Europe, and did not begin with France fighting against Protestant states. The Jews were not expelled from Spain in the late 16th century. It is bizarre to say that Cromwell was hostile to dissenters from the Church of England, that he wanted to establish a “fully functioning and comprehensive religious state”, and that his reason for contacting rabbis in Amsterdam was to ask them how to achieve that.

Naples and Milan were not “city-states”; the former was a kingdom and the latter a duchy. Trinity was not “the most Puritan college in Cambridge”. And no, Mortlake did not get its name from a waterlogged burial pit for plague victims in 1665. Residents of SW14 may be relieved to know that it was called “Mortelage” in the Domesday Book.

I can even derive that last detail from Wikipedia, which is another source cited quite often by Strathern. Alas, on too many of these issues, readers would do better to stick to that source, and cut out the middle-man.

Noel Malcolm’s latest book is Forbidden Desire in Early Modern Europe: Male-Male Sexual Relations, 1400-1750. Dark Brilliance: The Age of Reason from Descartes to Peter the Great is published by Atlantic at £25. To order your copy for £19.99, call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph Books