In “Hearts of Our People,” Indigenous Women Reclaim Space Through Art

Art has served as an outlet for indigenous women to carry on their traditional crafts and stories for centuries. They’ve continued to create even while contending with legacies of unimaginable oppression, like the residential and boarding schools many were forced into throughout the 19th century in the United States, in which colonizers attempted to wipe out their culture and assimilate them into a white, Christian way of life.

Today, their works are heavily referenced in mainstream fashion and design, and often without acknowledgment; indigenous women artists are frequently victims of cultural appropriation. It seems undoubtedly related to this erasure that there has yet to be a major retrospective in a major museum devoted to exploring these women—until now.

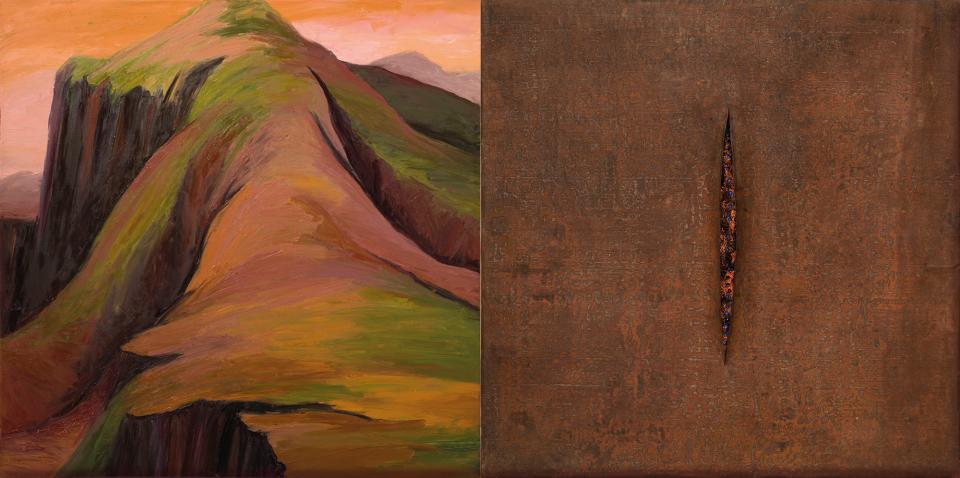

Through August 18, the Minneapolis Institute of Art (MIA) is presenting “Hearts of Our People: Native Women Artists,” the first major showcase to provide visibility to the indigenous women, both from Canada and the United States, who have repeatedly been ignored in the mainstream art world. Curated by Teri Greeves and Jill Ahlberg Yohe, it features 117 different objects, all made by native women, that span more than 1,000 years, including paintings, sculptures, garments, and more. The artists themselves also range in tribe and location.

"Hearts of our People: Native Women Artists" Exhibit Photos

The project has been a long time coming for curators Yohe and Greeves. The pair have been working on this project for more than four years, and during the acquisition process, the duo worked with an advisory board of 21 different native artists and scholars to ensure that the final selection represented the right mix of region, medium, and tribe.“Neither one of us could speak with authority on all these other nations,” said Greeves, while Yohe added, “To tell a story that’s as rich as this, we can’t tell that story. The board helped us make sure that we were comprehensive in scope.” To accomplish their goal, the curators split the exhibit into three themes: legacy, relationship, and power.

Inside, the works manage to do these big ideas justice. Power, for example, comes roaring at you at high speed: A totally customized El Camino, made by the mixed-media artist Rose B. Simpson, a Santa Clara Pueblo, opens the show. With her work, Maria, she presents herself as a petrolhead—something viewed as a very masculine hobby—then gives it a native woman’s twist, outfitting the car with decals inspired by the lines found in Pueblo ceramics, which are often made and mastered by women.

In another room, a large-scale painting, titled The Wisdom of the Universe, by Métis artist Christi Belcourt—painted in a dotted style, to give her canvas the appearance of being beaded—explores the relationship between indigenous people and nature. Animals, plants, and water hold a sacred place in indigenous life, and Belcourt specifically refers to 21st-century climate change, only painting species that are on Canada’s endangered list. It’s an extremely beautiful piece with an ugly message at its core.

Meanwhile, Legacy is a theme that runs through just about every piece in the show. A standout sample is the collaboration jewelry, titled Adornment: Iconic Perceptions, by Kiowa jeweler Keri Ataumbi and Shoshone-Bannock and Luiseño artist Jamie Okuma, both profiled for Vogue here. On a glimmering cocktail ring and necklace, Okuma beaded portraits of Pocahontas, based on historical illustrations of her in the 17th and 18th century; Ataumbi then set Okuma’s beading with precious metal, pearls, and stones. They are fabulous pieces of fashion that reimagine a historical figure who has long been misunderstood and stereotyped.

In general, the fashion pieces show just how much indigenous art has evolved, and they cut through any myth of its homogeneity. An Anishinaabe jingle dress and beaded headband from the 1900s evokes the flapper-style silhouettes that dominated the time period, showing that a traditional garment can even reflect the current trends of the day. Another piece by Okuma, a hand-beaded pair of Christian Louboutin platforms, combines traditional craft with an ultramodern flourish.

One can’t help but notice the timing of a show like “Hearts of Our People.” Women’s rights are increasingly under attack in America; controversial, draconian laws, for example, threaten to overture Roe v. Wade. Revisiting traumas specific to indigenous women and connecting to their struggles through solidarity—that’s something Greeves believes this show can provide.

“This exhibit was supposed to open in 2016, when Hillary [Clinton] was supposed to be president. Then the election happened,” Greeves said. “I realized, Everything happens for a reason. This kind of showing of native women’s effect on American art, making that declaration now and making a stand on women’s power, is actually healing medicine for this moment. This is happening when it’s supposed to be happening.”

Originally Appeared on Vogue