Having Polio As a Child Prepared Me to Survive the Covid Pandemic

A virus with no cure or vaccine, quarantining, not being able to see a single member of my family...I’m deeply saddened by the Covid pandemic, like everyone else. And sometimes, thinking about it makes me go drifting back to the loneliest period of my life.

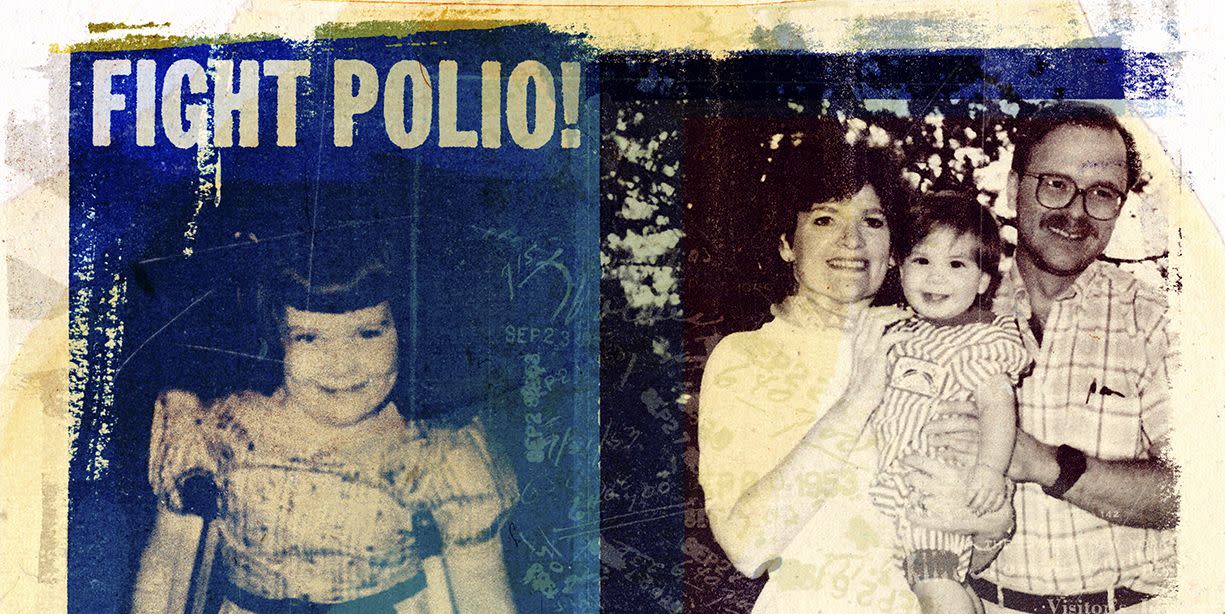

The first time I heard the word polio was over my shoulder. Parents at the time were terrified—they had seen March of Dimes posters of children in leg braces, newspaper pictures of rows of patients in iron lungs. But my mother maintained a low-key, “don’t scare the inmates” response to fear-inspiring events, at least among me and my brothers. Then one day when I was 5 years old, I was playing in our driveway with the neighborhood kids, and I suddenly felt ice-cold. As I was struggling up the front steps, a girl behind me said to my mother, “Mrs. Tully, she could have polio; my uncle does.”

That was September 15, 1953—as an Irish Catholic girl, I always recall that I got polio on the feast of Our Lady of Sorrows. Within three days, my muscle pain turned into paralysis; I lost the ability to get up. My parents took me to the hospital for a spinal tap, the only way to diagnose polio back then. When they knew I had it, the doctors put me in an isolation room. My folks were allowed to visit for only 15 minutes twice a day and had to stay at the door the entire time. The toys they brought me had to be burned for fear of infection. When I see pictures of people waving at their loved ones through nursing-home windows now, I remember how terrible that was.

I lay in that bed for ten days. I couldn’t move anything but my head. When my fever finally broke, I was taken to St. Charles, a little Catholic hospital not too far from our home in Brooklyn that was run by nuns—the Daughters of Wisdom. The 17 of us in the girls’ ward lived in an alternate universe, with a schoolroom set up for kids in beds and wheelchairs.

I’ll never forget the loneliness of that time, or the pain. Polio makes your muscles contract and paralyze; I had to lie there while the physical therapists tried to stretch them out again. After three months of excruciating physical therapy, a doctor said to my mother, “Good news—her toe is moving.” Mom’s reaction was, “You can do better than that.” She always made me feel that I could do whatever I wanted. After a while I walked with back and leg braces and crutches, and used a wheelchair for distance.

After two years in the hospital, I got to go home. While I thought I’d keep getting better and end up like everybody else, eventually the doctors told me my condition would never improve. That was the hardest thing to hear. Luckily, our local school got an elevator, so I was able to attend, starting in seventh grade. Trying to fit in gave me something to focus on—from then on, my goal was to live as normally as I could.

When I was 24, I moved to Seattle, away from the close-knit family I relied on, and built my own life working with troubled teens, then in sex education related to disabilities. I met a gorgeous guy at an Alfred Hitchcock festival when he offered to push my wheelchair up the hill. We got married and adopted a son I’m crazy about.

Once I got post-polio syndrome, I had to use a wheelchair permanently, plus a vent to help me breathe. Then I concentrated on being a mom. The doctors told me I shouldn’t expect to live past 30, so I’m grateful that I’ve extended my sell-by date by four decades. And that we got a vaccine, even if it came too late for me.

I love being alive; I feel there are still things I can do. Not all of those girls who were in St. Charles with me made it. I remember them, and I try to justify the fact that I got to keep going.

For more stories like this, sign up for our newsletter.

You Might Also Like