You Haven't Met the Real Chasten Buttigieg Yet

Midway through our phone conversation, Chasten Buttigieg pauses to duck out of view. A stranger has come to his door to get a glimpse of him, his Twitter-famous dogs, or his husband Pete, a former presidential candidate. Does this happen often? "It's a tourist destination," Buttigieg quips wearily.

I haven't read the terms and conditions of Hinge, the dating app where Chasten and Pete met, but I'm fairly certain they don't say anything about rocketing to national fame and having your home descended upon by looky-loos like it's a stop on a Civil War walking tour. But that's, essentially, what happened: Chasten and Pete went on a first date that ended with literal fireworks; they married; Pete ran for president, and soon thereafter, Chasten's perpetually cheery and approachable online and IRL presence made him a campaign bright spot. It also exposed him to a level of scrutiny and criticism of his politics, his relationship, and his place in the queer community that, again, is probably not one of Hinge's selling points.

"I felt a lot of people were asking me to behave in very different ways," he says, reflecting on the campaign. "The only thing I could do was be myself, because at the end of the day, if people liked it, then at least I was being myself. If people had a problem, if they hated it, well, at least you hate me. It’s not like you hate the character I’m pretending to be."

In his new memoir I Have Something to Tell You, Buttigieg opens up about being adored and reviled online and his true motivations. He also offers a glimpse into the day-to-day side of his very public relationship, which in quarantine has involved a lot fewer public rallies and a lot more long dinners and little love notes left around their South Bend, Indiana home. "Sometimes the partnership that I love the most is checking in with one another," he says. "I'm carrying a lot of anxiety. [Pete's] really good at being there. It doesn't mean he has the answers, but it's really nice to have somebody you can lean on."

Buttigieg speaks with ELLE.com about growing into politics, the shifting dynamics of his marriage, and responding to his critics.

In the book, you recount the time your dad tested your self-sufficiency by leaving you alone in the forest and watching from across the river. Later, your self-sufficiency becomes a lifeline for you, from sleeping in your car to working multiple jobs in Chicago to navigating a complicated and unique role in the campaign. The thing about self-sufficiency, though, is that it has to come from the self. How do you keep your tank filled if you have to keep relying on your own skills to get you through these new and scary experiences?

For a long part of my life, I thought the phrase “It gets better” was bullshit. Like I wrote about, there were a lot of times I stared at the gun safe and never did anything about it. I truly wanted to know better. When I started teaching, I knew that in order to see better, I had to be part of what would make better. And at some point there is a realization: It's never going to be what I wanted it to be, but I can do something about making sure it is for the next person.

I always felt it was important for me to assert myself in a way that built other people up, even though for a long period of my life, I was breaking on the inside. I found purpose and serenity in trying to help other people.

You write with stark vulnerability about the relationship dynamics of your marriage. I'm thinking in particular about the moment you had to reveal your student loan debt to Pete. You write, "What did I have to offer him in return?" One of the things that was hard for me growing up was not having other gay or queer long-term relationships in the public eye to give me a model. What models do you use for making and building a healthy relationship?

That makes me think about all the queer authors and outlets who wrote about us as being straight men without women and traitors to the movement and performing queerness like we were just a heteronormative couple. Everything I have grown up knowing is heteronormative. People ask us these questions: "Why did you get down on one knee?" and "Why did he propose?" It's like, "I have grown up in a heteronormative society. It's not that I said these are the things I wanted. I think these are the things we expected."

And then people wrote about us as if we were trying to be straight. I was never trying to be anything. I have seen an extremely healthy and successful relationship with my parents. I have seen a very loving, stable, committed, dedicated—if not overly dedicated—family unit in my larger family, and I know what partnership looks like through the good and the bad. But that's all modeled by straight people. I approached this partnership through the lessons I have learned throughout my life [and] not trying to make it anything other than healthy and loving.

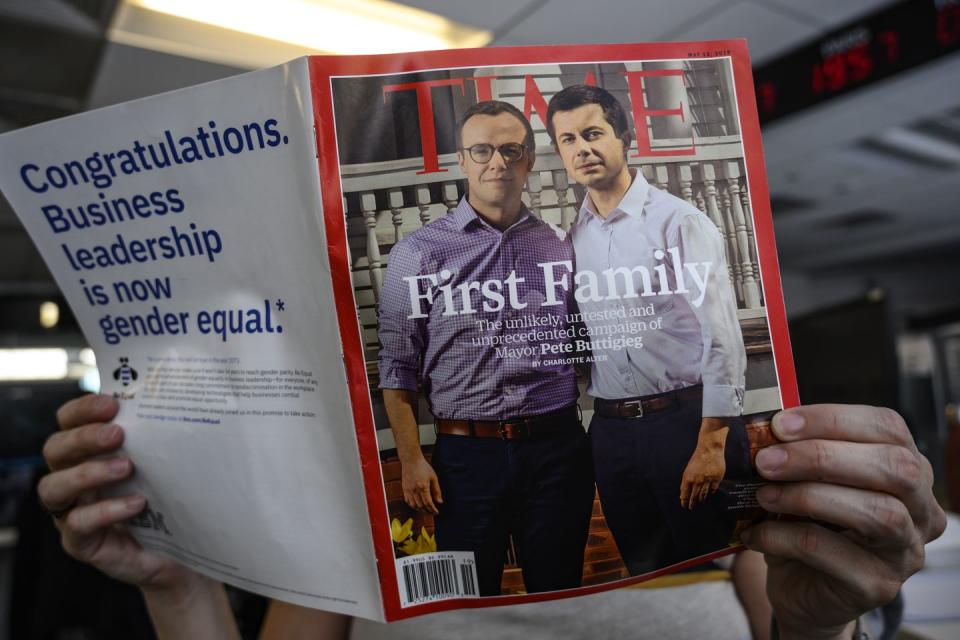

It's funny you raise that question, what gay couples did I feel modeled a successful relationship. I can't think of any. But then it was thrust on us. I remember the critical theory and feedback on that Time magazine cover was like, "We're just like straight men and chinos."

One, had I known I was going to be on the cover, I maybe would have worn something else. But two, why? What are we doing? How is it helpful? How is it constructive? If you think I'm not performing my identity in a certain way, what does it say about other people's identity? Do they have to perform in a certain way to be deserving of dignity and respect and love from our community?

I wonder how much of it is also the fact that you are cisgender white men. There's competing levels of privilege you have to negotiate, so people were putting all these intersecting identities on top of you. A lot of the critique may be more about whiteness and a certain income level than about gayness. Does that resonate in any way?

It does actually. And I felt like perhaps some criticisms were proffered unfairly when they weren't listening to the things we were saying out on the trail. The ways in which Pete talked about whiteness and how the work falls on white people, and the way he was talking about racism being a public health crisis in this country. I don't want to go down that rabbit hole of how he was portrayed and what happened in the campaign, but I also felt a lot of the criticisms about our queerness and our identity weren't actually rooted in our queerness. They were rooted in other criticisms of the campaign, or they were an easy way to nflict pain or strike the campaign.

In the book, you talk about the presence of Confederate flags in Michigan. "I was swimming in a sea of whiteness and I didn't even know I was wet." As a Black person, I'm interested in how white people learn about whiteness and what they do with that information. You've lived this dichotomy of being in a sea of whiteness that's uncommented on, but also being a queer person and living through this identity that is constantly commented on. How do you navigate those different levels of power and privilege?

When I was growing up, I was learning very rapidly [that] if you were not a straight white man then you were therefore different and weaker and less than. When it came to race and sexuality, I had a lot of input coming in from people in my worldview. I should say some people, not a lot of people, talked about queer people and people of color really negatively. It really wasn't until I went to college, surrounded by more ignorant young white people, that I was able to start having those conversations—but only if people were willing to have them.

[University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire, Buttigieg's alma mater] is still predominantly white, and so I had more queer theory than race theory in college. Then I moved to Milwaukee, where I had the first advisors, people who were helping me navigate education in the classroom, where I was having legitimate, concrete conversations about race, especially as it related to the classroom, like poverty, red-lining, school districts.

Obviously, I'm really sensitive to how much space I'm taking up in this conversation. I don't know how I'm the most critical voice on the topic, but I wanted to be really honest: "Oh, I grew up in a pretty racist structure and I had to unlearn that." It took me awhile to become an adult. And I think a lot of white people just don't want to believe they were ever part of the problem.

One aspect of your college awakening was playing Louis in Angels in America. Can you talk about that experience?

I took this class, it was depictions of gays in America, depictions of gays in media. And I started reading queer drama. I was like, "Hold on. You mean to tell me..." I didn't even know that queer authors existed. That is what I thought growing up in Northern Michigan. And then the university did Angels in America. It was eye-opening. It was really moving because the semester before we read The Normal Heart. It was one of the first times I had actually been able to study and examine the AIDS epidemic and learn a whole different side of our community.

There's this part at the beginning of Angels in America: Perestroika where the oldest living Bolshevik says, "The great question before us is, are we doomed?" I think about that so much. I've been thinking about it recently with the pandemic and the collapse of different political systems. But I also feel like art has a unique ability to show us that we are not alone, and to pose really scary questions and offer hope at the same time. As both a teacher and a theater artist and now a writer, have you been able to keep making those kinds of discoveries and finding those challenges?

That what I hope people get out of the book, those big questions and vulnerabilities. That's why I wrote the book the way I did, because I hope other people actually see themselves in it and then see somebody in this world navigating it in a very different way than most people they're used to seeing in that political world. I want to keep having those authentic conversations with people, especially in the political world, because we have to. People are giving up and we have to restore that trust in our institutions and the people who represent us.

You've lived a very public couple of years, but writing a book is a different kind of relationship with the public. Does it feel like a different kind of vulnerability for you?

I think I was successful on the campaign trail because I was just myself: The more I was vulnerable, the more I opened up, the more I talked about things that scared me even though they shaped me. I felt like people saw themselves reflected in the campaign, and young queer people at LGBTQ centers or homeless shelters would be like, "This is what I experienced. This is what I went through. This is what I navigated."

I felt like people believed in the campaign more because they could see themselves reflected in it. I feel like politics is so often a veneer of polish and mystery, and you're not supposed to be vulnerable, you're not supposed to talk about the hard stuff. For a long time, I didn't consider myself political, although, I guess, now I technically am. But I just wanted people to feel like they were actually getting to know the real me.

Do you think there's room for nuance and vulnerability in our political system?

People are done with the bullshit. "How do I truly believe you're going to Washington and fighting for my best interests? I don't even know who you are. How do I know that you understand what it's like to be a suicidal teenager, running away from his family, trying to navigate college?" That's why I didn't even look or listen to politicians when I was that age. I figured they didn't care about me. I think a lot of people are giving up, and if you really want to reclaim this trust in our institutions, then you better start talking to people about things they really want to talk about, or connecting with them in a way that makes them feel seen and heard. For me, on the campaign trail, it was like, “Life's been pretty sticky, and confusing, and muddy, and heartbreaking, and here we are. This is the person I am today and I'm not going to lie about some 'pulled myself up by the bootstrap' story. Here's how politics happened to me.”

There are portions of your book that reminded me of Michelle Obama's book, Becoming. There's an anecdote she tells about the night of the Marriage Equality ruling, and people are gathered outside the White House. She has to try to sneak out in order to see them. It feels like we sometimes make people in public political positions remove themselves from being a part of real life. Is that true? Or is it more that you have to hold some of yourself closer to the vest?

I think both are true, but I do believe in politics we separate the person from the politician. So often on the campaign trail, I felt like when people were being really nasty, it was like, "I don't know if this person would ever say that to my face." Or if they would say it on a debate stage, or if they would say it in front of a reporter. But they're very comfortable saying it on Twitter. That's the scary part about social media, we remove the humanity from these people, and politicians start to become figures for what they represent.

I wonder about Twitter as a lens through which you navigated self-expression while also also avoiding becoming too enmeshed in fan culture.

Sometimes if I don't go on Twitter for a day or two and get on there, I'm like, "Why did I come back here?" It can be so nasty. But then I come back because I want to add to the good, and I love following people who are funny and inspiring and who are doing the work, and who would teach me things and inspire me to be a better person, or sharing things I need to know. Then I get worried when I see people tearing each other apart: for what?

I would meet people—sometimes it would be alarming and not necessarily off-putting, it was just so new—and they had my face on their t-shirts and they knew so much about me and I knew nothing about them. It was like, "Oh, they will never actually get to know the real me." On the campaign trail I was like, "Even though I feel like I'm not pretending to be anybody else, many people are getting to know me simply by what's written about me or by what I post."

It seems like it's such a losing proposition. Part of me wonders now, why not go wander the woods in Chappaqua? Why continue to be in public life?

Because it matters. There are many times on the campaign where I was like, "You know what, I'm out. If this is the way people are going to talk about me, if I'm going to get threats, if people are going to show up on my parents' doorstep, if this is what it takes." You're constantly under the microscope, it's extremely invasive, and it's hard on a relationship. People want to dig.

But then you would go out there and sit at this LGBTQ center and talk with 20 teenagers, and the hope in their eyes was like, "Oh my God, this is the gas to get me through this day." When you use that platform for good and you see the good that can come from it, it's very rewarding. I think [Pete] understood well the sacrifices required when you want to go into public service. For me it was like, sometimes I just wanted to go home. Sometimes I did. Especially when it started getting really nasty and people would show up and knock on your car window and flip you off and spit at you, even people from our own party, from a different candidate, it's just like, "What are we doing?" It takes a lot of discipline, but if you can focus on the better—and truthfully, this is not my political answer—the benefits I see from using the platform for good get me through the other moments.

That's beautiful. It's so funny: I'm like, "Hmm, I believe you."

Even as a teacher, you never get immediate feedback, especially when you're teaching seventh grade. They all honestly hate you. And then they grow up to be fine adults. On the campaign trail, an older gay couple, maybe in their 60s, came up to us on the rope line, drove hours from their hometown because they didn't want anyone to see them at a Pete event. So they went to a different state to go to a Pete event because they couldn't be out because they lived in this little town where everybody knew everybody.

You meet these people and they would just tell you these most heartwarming things. You're like, "Oh my God, I'm doing that simply by existing. I can put up with some of the other things that make it really hard, because sometimes, the good is, like, so good."

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity and length.

You Might Also Like