Hate Crime Laws Won’t Deliver Justice to AAPI Communities

Soon after the Atlanta massacre gained national attention, President Joe Biden called on Congress to swiftly pass the Covid-19 Hate Crimes Act, a bill introduced by congressional Democrats Representative Grace Meng and Senator Mazie Hirono. “While we do not yet know motive,” Biden said in a statement last Friday, “we condemn in the strongest possible terms the ongoing crisis of gender-based and anti-Asian violence that has long plagued our nation.” The bill would designate an official at the Department of Justice to review COVID-19-related hate crimes reported to law enforcement, establish an online database of these incidents, and expand public education campaigns to mitigate racially incendiary language around the pandemic. In other words, as all hate crime legislation does, it enhances the scope of the carceral state.

To the starving, rotten fruit is better than an empty plate. At least, that’s how I rationalize the current widespread demands for the U.S. justice system to recognize the massage parlor shootings—when a white man shot and killed eight people, six of them being Asian women—as a hate crime.

How else are we to understand their deaths? Though the Cherokee County Sheriff’s Office may peddle the killer’s claims that the murderous rampage was merely the culmination of a “bad day” and “that it was not racially motivated,” Asian-American and Pacific Islander communities know better. This is the kind of putrid rancor that has enabled a meteoric rise of incidents of assault or discrimination against us over the past year, especially as phrases like “kung flu” or “China virus” have transformed our daily lexicon into minefields that we now tiptoe through, afraid of what or who we may set off. This, too, is the same enmity that justifies the ongoing subjugation of our people at home and abroad, be it the racial fetishization of Asian women, the jarring wealth gap within AAPI communities, or the inescapable fearmongering of Western media against China. Whether or not the advent of new legislation establishes more accessible hate crime databases—statistics that fail to grasp the true magnitude of discriminatory violence since many who are harmed don’t necessarily report their experiences to law enforcement—we’re already deeply intimate with this brand of vitriol directed toward us.

Yet, countering our tragedies with hate crime laws is the task of the agents of a system buttressed by centuries of imperialist conquest and white supremacist ideology. For harmed communities righteously calling for justice and healing, the policymakers bearing the power to shape our day-to-day lives offer us hate crime laws or nothing: rotten fruit or an empty plate. But when we allow the mechanisms of this country’s carceral apparatus to define the contours not only of our grief but also of our restitution, we only become further ensnared in a system that never meant to include us to begin with. We lose the chance to imagine and build a truly equitable world—on our own terms.

The United States first recognized hate crimes with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1968, which established race, religion, and national origin as protected categories. The breadth of hate crime prosecution expanded to apply to gender, gender identity, and sexual orientation in 2009 after the horrific, high-profile murders of Matthew Shepard, a gay man, and James Byrd Jr., a Black man, led President Barack Obama to sign the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act. Still, hate crime statutes can vary dramatically state by state. Today, Arkansas, South Carolina, and Wyoming have no hate crime laws in the books.

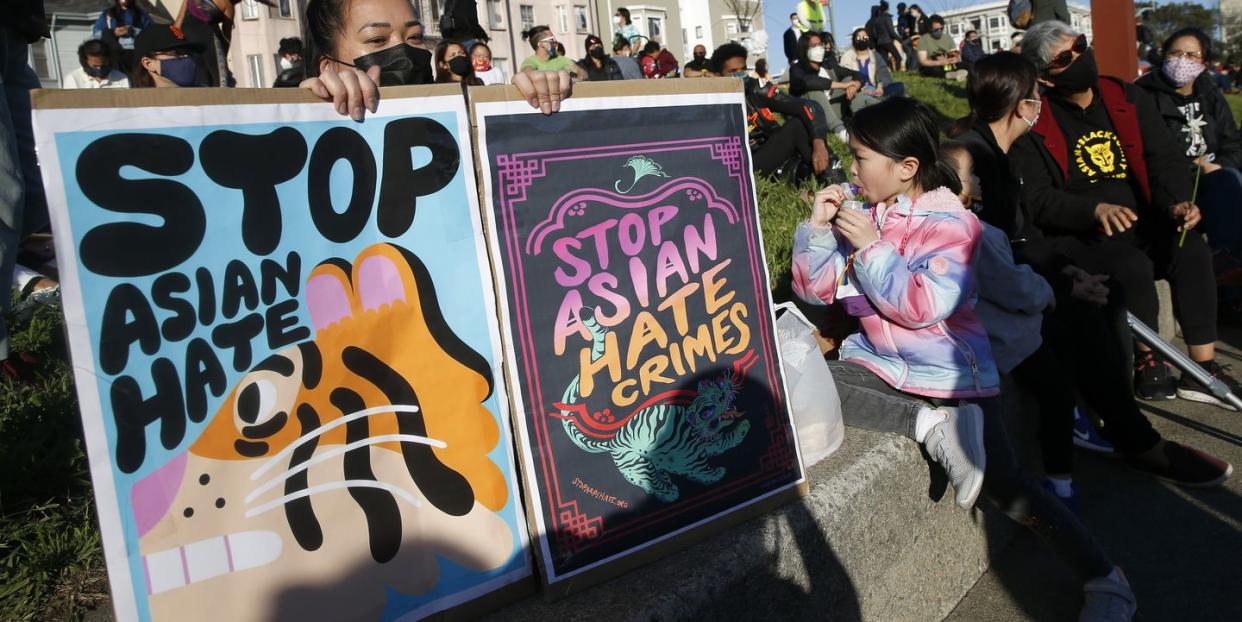

Interest in hate crime legislation within AAPI communities has unsurprisingly surged amid an uptick in anti-Asian violence since the outbreak of the pandemic. Last year, though the rate of hate crimes decreased overall, hate crimes targeting Asians rose by nearly 150 percent, according to the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino. And from about mid-March of last year to the end of February this year, Stop AAPI Hate found 3,795 self-reported hate incidents targeting Asians. We see this onslaught of cruelty manifesting especially against our elders: A 91-year-old Chinese man gets pushed to the ground in Oakland; a 61-year-old Filipino man gets slashed in face while riding the New York City subway; a 76-year-old Chinese woman is left bloodied and bruised after an attack on a crowded San Francisco street.

When, in our bereavement, the government offers hate crime legislation as the only means of achieving safety and of recognizing our pain, it’s natural that we may find ourselves in a position to be seduced. After all, don’t hate crime laws, at the very least, legitimize our grief and deem our lives worthy of protection and safeguarding? The truth is that these tragedies, the unnecessary loss of life, the perpetually violent pursuit of our people and oppressed peoples everywhere, can never be synthesized under an inherently oppressive system.

To the layman, hate crime laws (or any kind of ostensibly justice-oriented policy) would be designed to prevent such attacks from even happening, but this isn’t so. Instead, hate crime laws merely enhance punishment for perpetrators, piling on additional years of incarceration or changing the classification of a misdemeanor to a felony. Time and time again, the evidence shows that the threat of incarceration doesn’t deter harm from occurring.

Hate crime laws rarely even work. Since the burden is on the prosecutor to provide proof of someone’s motive, there are few hate crime prosecutions and even fewer convictions. In Texas, for instance, ProPublica found that, out of the 981 cases reported to law enforcement from 2010 to 2015, only five cases resulted in convictions. Many people at the center of hate violence also don’t report these incidents to the police due to language barriers, immigration status, or just general distrust of law enforcement. This, as well as the fact that the federal government doesn’t require every state to report its hate crime statistics, likely contributes to a vast undercount that muddies the national data.

But this inefficiency doesn’t signify that we need improved, well-oiled legislative machines that can better equip the carceral system to prosecute, convict, and incarcerate perpetrators. Rather, abolition points to how the very act of disappearing people into the vacuum of the prison industrial complex doesn’t foment justice in the first place. For some perpetrators of violence and harm—who undoubtedly must face accountability—prison acts as an incubator to extreme alt-right radicalization, further stoking white supremacist ideology or interracial antagonisms. Expanding the scope of the carceral state (which includes policing, surveillance, and incarceration) also disproportionately affects marginalized communities—the exact people these laws are purported to protect. In 2019, for example, though Black people made up about 13 percent of the U.S. population, they were accused of nearly 24 percent of hate crimes by law enforcement, reported The Marshall Project. By comparison, white people, who make up about 60 percent of the population, were accused of less than 53 percent of hate crimes.

It’s not just that hate crime legislation fails to deter violence or rehabilitate a perpetrator once violence is committed; it’s that prison, and the entire institution that bolsters it, is wholly incapable of meeting either of those standards. When laws focus on punishment rather than reparation, it obscures what is a systemic issue into an individual one. In this way, hate crime laws are successful only in that they deflect attention away from the true culprit: a capitalist empire that favors profit over life, that was built on and continues to perpetuate white supremacist dogma, that bloats the budgets for prisons and militarization while starving communities and public infrastructure.

“One question that we abolitionists ask ourselves is, What are the conditions under which it is more likely that people will resort to using violence and harm to solve problems?” said Ruth Wilson Gilmore, the iconic prison abolitionist and educator, on Intercepted. “What can we do about it so that there is less harm?”

If what we want is to end anti-Asian racism—indeed, all forms of racism—then we cannot expect hate crime laws to deliver us there. The kind of insidious hatred that drove the Atlanta shooter to claim eight lives thrives in tandem with the historical, state-sanctioned violence against our people, whether in the United States or in our ancestral homelands. The two cannot be solved as separate entities, and a true liberation project requires that we undertake the hard work of acknowledging that, however daunting or overwhelming it may seem.

More than just divesting from police and prisons, we achieve safety and justice when we invest in each other. From this vantage point, abolition intersects all other issues; organizing for housing, health care, and environmental justice naturally complements the work of ending jail expansion, defunding police budgets, and closing ICE detention centers. As targeted attacks against the AAPI community make national headlines, people on the ground are also already working on building models of care and wellness that don’t require increased criminalization. Groups like Red Canary Song, CAAAV, and the Asian Pacific Environmental Network are plowing ahead in grassroots organizing for working-class and migrant Asians. In Oakland, California, volunteers are accompanying people in Chinatown while they run errands. And for the families of the slain victims in Atlanta, nearly all of their GoFundMes have exceeded their goals by tens thousands of dollars.

We can hold the agents of white supremacy accountable, too, without perpetuating the power of the inherently racist, anti-Black, and corrupt carceral state. Kay Whitlock, a prison abolitionist and LGBTQ+ advocate, writes for Truthout, “The concept of ‘consequences’ must have teeth and be tied directly to organizing efforts to build broad-based community support for standing up to all forms of white supremacist violence.” This can look like national or local public campaigns seeking to expose white supremacists, draining them of their financial resources or removing them from the powerful offices they may occupy.

Abolition challenges us to look beyond the carceral state for the means of our liberation. It is an active, exhausting pursuit, one that requires us to sometimes defend our non-carceral positions from the naysayers and skeptics while simultaneously grieving for our communities. But it’s this grief that drives me, that demands we don’t settle for platitudes and bread crumbs that do little else than continue to feed the insatiable hole at the center of the prison industrial complex. Under abolition, we need not choose between what is rotten or what is empty. There’s more than enough for each of us, should we all—together—be willing to seize it.

You Might Also Like