Harmony Korine, Glorious Weirdo

When the filmmaker Harmony Korine was young, and interviewers would ask him about his past, he would tell stories. Some of these stories, in retrospect, were probably truer than others. In 1995, while promoting Kids, the controversial Larry Clark film for which Korine had written the screenplay as a 19-year-old living in his grandmother's apartment in Queens, Korine was invited onto the Late Show with David Letterman. Letterman, bemused at the tiny person in a giant suit who'd appeared in front of him, asked Korine how he had come to write Kids. “I just wanted to make a sequel to Caddyshack,” Korine told his host. “And I used to live by this guy and he was Hasidic Jewish and he always played with basketballs, and also his father was a dentist. But once, I was walking down the street and he said ‘You're a sinner!’ like that. So I just wrote it.” Later, Korine would be banned from the show, for pushing Meryl Streep backstage—or maybe it was for going through her purse. Like many things with Korine, the precise truth remains elusive.

As Korine's career went on, he did his best to live up to the fictions. He refused most work within the Hollywood system, except on his own abstruse scripts. Two of his homes in the '90s, in New York and Connecticut, burned down under mysterious circumstances. In the Connecticut fire, he lost most of the footage of what was to be his third feature as a director, after 1997's Gummo, a series of unrelated and often disturbing vignettes that took place in Ohio and were inspired by the neighborhoods he'd grown up in around Nashville, and 1999's Julien Donkey-Boy, about a schizophrenic boy and his unhinged family, the patriarch of which was played by the German director and Korine mentor Werner Herzog. The third film was called Fight Harm: It was going to consist entirely of real footage of Korine being beaten up in various violent confrontations that he initiated. Two of the cameramen on the project were Leonardo DiCaprio and the magician David Blaine. “At that time, I thought it would be the greatest comedy the world had ever seen,” Korine told me.

As the '90s ran out, Korine left New York for Europe, where he spent years in the grips of paranoia and drugs. (He also remembers, fondly, eating a McRib on the Rue de Rivoli.) He wouldn't make a film again for nearly a decade. When he did return, with 2007's Mister Lonely, a tender movie about a Michael Jackson impersonator, played by Diego Luna, living a solitary life in Paris, Korine told interviewers about the Malingerers. The Malingerers, he said, were a cult of fishermen living in Panama who had dedicated themselves to searching for a fish with golden scales. Korine claimed to have stayed with them for months before accusing their leader of living a lie, after which he absconded from the group. By that time he was sober, back in Nashville, and, after a stint mowing lawns and wondering if he had anything else to say, making films again. In 2009, he directed Trash Humpers, a disquieting, harshly lo-fi but genuinely heartfelt film about societal outcasts (played by, among others, Korine and his wife, Rachel) who fuck trash. And then, in 2012, he made Spring Breakers, a nonlinear, acid-dream crime story set in northern Florida starring two former Disney stars in string bikinis, which grossed almost $32 million and became not just a pop sensation but also Korine's most successful film since Kids. (“Spring Breakers, I saw,” Jimmy Buffett, one of Korine's many unlikely friends, told me. “I went: ‘Jesus Christ!’ ”)

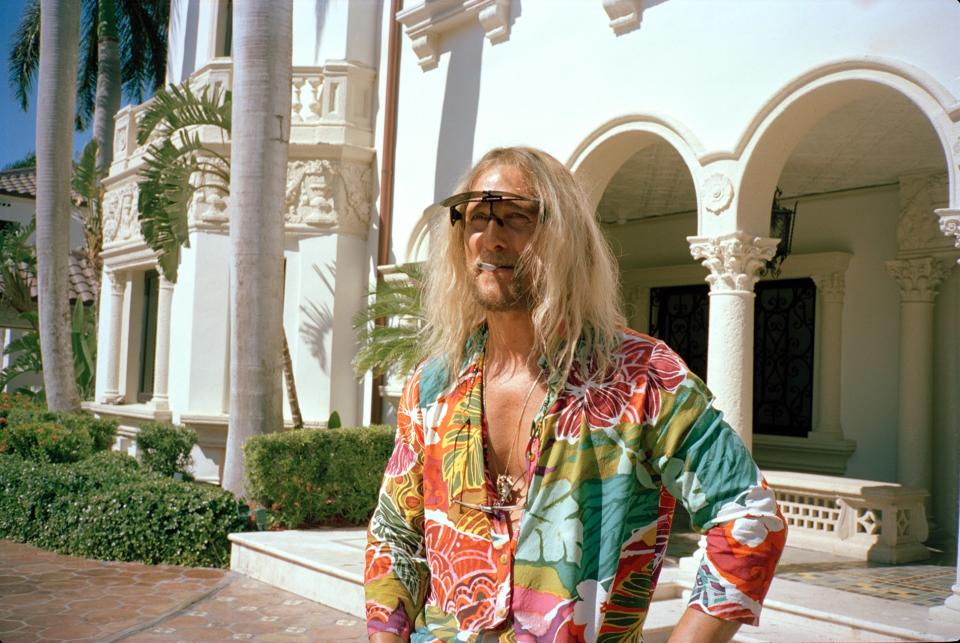

Korine's new film, The Beach Bum, stars Matthew McConaughey as a poet named Moondog—a guy not unlike McConaughey's Dazed and Confused character, if that character had moved to Key West and discovered acid, typewriters, and the freeing powers of matching short sets patterned from top to bottom in flames. The film is less a linear narrative than a character study, an extended hang with an extraordinary man. In an e-mail, McConaughey told me, “Moondog's a verb. A folk poet. A character in a Bob Dylan song dancing through life's pleasure and pain knowing every interaction is another ‘note’ in the tune of his life. His bliss of being high, hammered and freshly fucked, he'd rather shoot the lock than use the key. Not interested in the truth, he is inconsiderately ruthless in his quest for transcendence.”

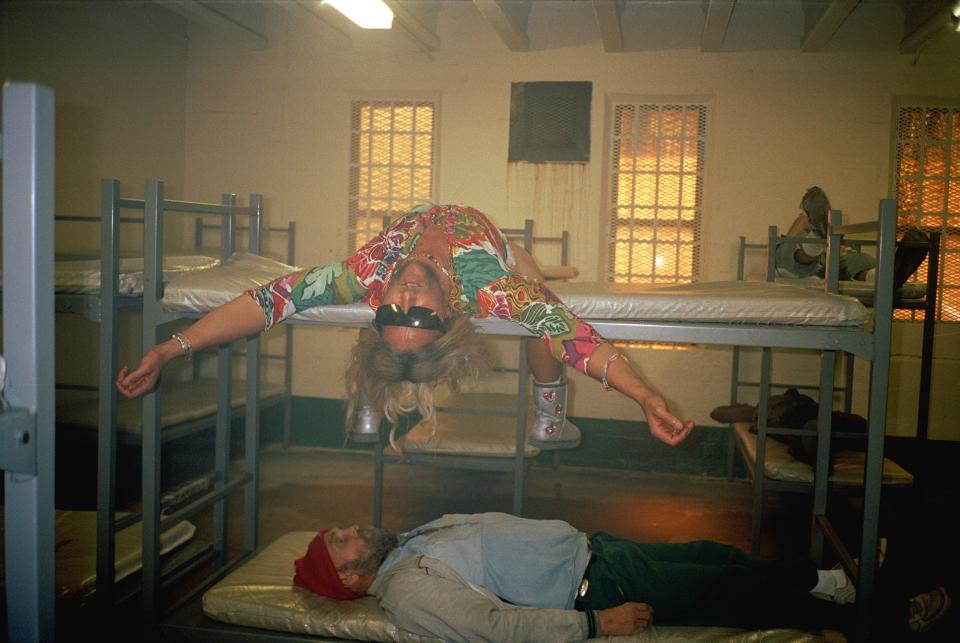

Moondog lives life among topless women, fishermen, and empty cans of PBR, often on the deck of a boat called Well Hung. Isla Fisher plays Moondog's rich Miami wife, who is having an affair with a drug runner and weed enthusiast, played by Snoop Dogg. There is an interlude with a selectively bearded Zac Efron, who loves vaping, Jesus, and sinning, and another with a boat captain and dolphin lover named Captain Whack, played by the comedian Martin Lawrence. It's maybe the most revealing and personal film Korine has ever made about art and life and how they relate: Moondog, like Korine, lives a life that aspires, in its wildness and freedom, to art; the art itself is just something he does occasionally, although very well, along the way.

In one scene, a nosy, inquisitive journalist visits Moondog in Florida to ask the poet about his past: Are the stories true? Did Moondog really do all the wild, reckless things he was rumored to have done? Korine and I were standing on a second-floor deck in Miami talking one afternoon when I told him I couldn't help but feel like we were re-enacting scenes from The Beach Bum. That, in some ways, I wondered if he'd written it in anticipation of this moment, here in the February sun, and all the moments like it before that Korine's endured in real life. (For instance: “I know his deep background, too,” Buffett said. “I don't want to get into that. But let's just say, when his dad was—uh, I was probably the background music to a few people in the pot business before legalization was around.” What did that mean?!)

“Yeah,” Korine said. “Well, a lot of people were always like, ‘Oh, he's making up everything.’ But mostly it's true.” He paused here for a very long time.

“Listen: The film, and the life, is a cosmic America, you know what I'm saying? And so the movie—that's what it is, it's a cosmic America. It's an energy that kind of travels through.”

You mean through your work, or his?

“Well, I'm saying—Moondog, he's tapped into a cosmic America, you know? Uh, and the way that I grew up, and the things that…”

He trailed off, then burst into exasperated laughter.

“What are you gonna do?” Korine said, shrugging.

Witness Matthew McConaughey at His Sun-Baked, Kitten-Cuddling Best

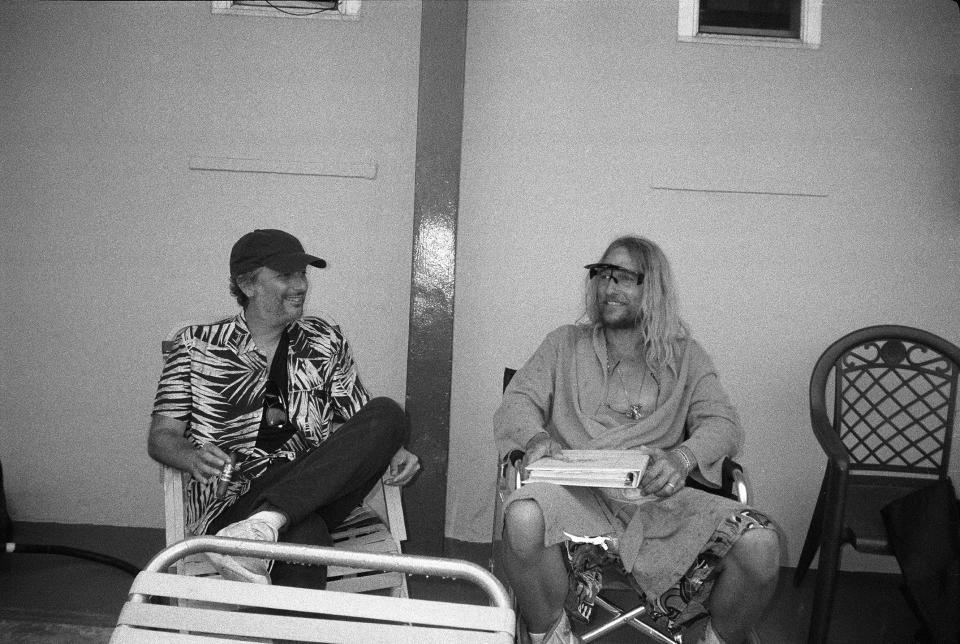

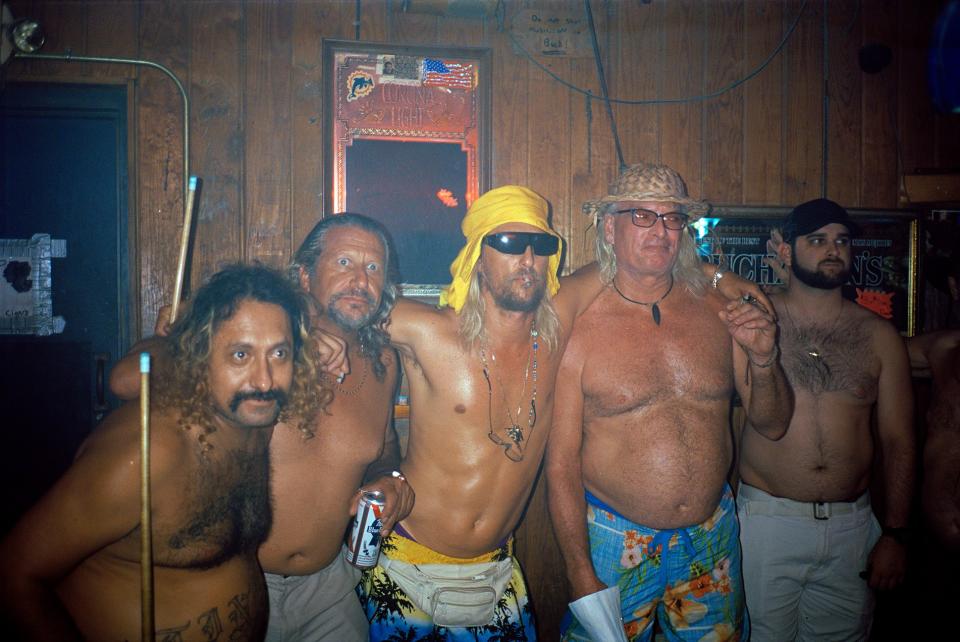

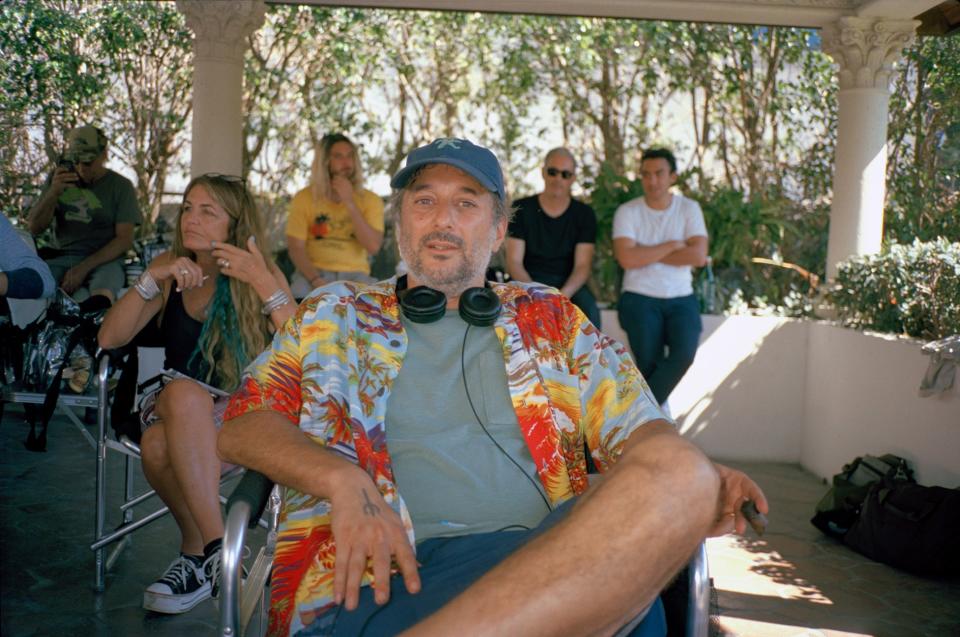

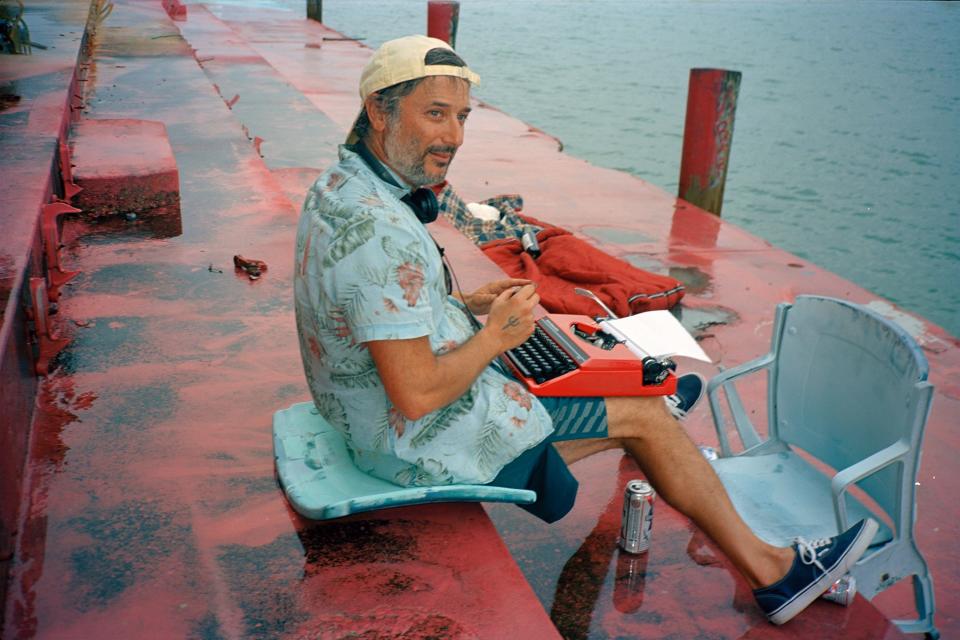

In these behind-the-scenes photos by photographer Sam Hayes from the set of Harmony Korine’s new film, The Beach Bum.

Witness Matthew McConaughey at His Sun-Baked, Kitten-Cuddling Best

![“Nobody had any problems with [the photos]. It was like, everybody was just doing their thing. It was for real. It all felt very natural, you know?”](https://s.yimg.com/ny/api/res/1.2/l3AAzFRnnsZdGt6C0niqSg--/YXBwaWQ9aGlnaGxhbmRlcjt3PTk2MDtoPTY0Nw--/https://media.zenfs.com/en/gq_402/2d187974cd279996fb75dac772398294)

Korine's studio is in Miami's Design District, on the second floor of a shopping mall. On the day I visited, he was wearing a baseball hat with a nautical emblem on it, a striped button-down shirt, and baseball cleats with metal spikes that echoed on the mall tile. Few people have ever looked so obviously mischievous. “This is so I don't wear out the bottoms of my shoes,” he said, shuffling loudly along. It was impossible to tell how sincere this explanation was.

The studio itself is a wide, carpeted room with two walls of windows, which Korine had blacked out last year in order to edit The Beach Bum. Now sunlight shone in on a series of paintings Korine had made for an upcoming exhibition at the Gagosian Gallery in New York. They were beautiful in the way that most of the images Korine has made as an adult are beautiful: shimmering with color, streaked with yellows and blues. One painting depicted his wife, Rachel, and newborn son, Hank. Another depicted what looked like his kitchen. On many of them, crude ghosts, sleeping or skateboarding or just observing, had been painted on top of otherwise domestic scenes.

“I like places that are undefinable. The history is only like 100 years here, so it’s really just inventing itself.”

Korine has always been a compulsive maker of things: zines, paintings, drawings, films, photographs, poems, myths, books, screenplays. When he was younger, Korine said, “I had so many ideas and images, I didn't know how to control them. All day, it was just coming to me.” Back then he couldn't sleep more than a few hours a night. Now, at 46, Korine has a little more control over his own creativity, he said. But his studio is still dense with the products of his overflowing mind: Cohiba cigar boxes painted in bright colors, scrawled with Korine's child-like writing. “People always make fake cigars. I wanted to make my own fakes,” he said. He showed me a bound manuscript that he said was a book of poems that he wrote entirely on his iPhone, using the Tom Hanks typewriter app. The manuscript's title was Destiny's Aborted Child.

Korine led me back out of his studio, through the empty mall, to an unfinished outdoor balcony on the building's second floor. From the concrete at our feet, he picked up a mostly smoked nub of a discarded cigar off the ground and lit it. We blinked in the sun. Korine and his family moved down to Miami from Nashville six or seven years ago. “I can relax here,” he said, gesturing around. “I also just really like the way it looks and feels. That's mostly what drew me to it in the first place: the redness of the sky, palm trees, salt water, the breeze, the iguanas, flamingos, the extreme wealth, the extreme hood—all smacked up against each other. I like places that are undefinable. The history is only like 100 years here, so it's really just inventing itself. I could never live in Europe or somewhere like that, because the history is so foreboding.”

In Miami, he said, he could smoke cigars, ride his bike on the boardwalk, go fishing in the Keys, visit the dog track. His kids could go outside. He could spend most of his time painting and enjoying an unobserved life. For money, he directed music videos and commercials—one or two a year, for companies that he didn't find it humiliating to work for. He shot a Gucci campaign last month, he told me. Like Moondog in The Beach Bum, Korine seems to make the work he's best known for only when he's compelled to. “I'm not super prolific,” Korine said. “I think this is only the sixth movie I've made. I never really understood the directors who have, like, ten projects lined up. I don't really trust those types of people. How do you map it all out like that? I can't trust you. How do you know what you're gonna be like tomorrow?”

Shortly after Korine made Spring Breakers and then moved to Miami, he tried to make a violent gangster movie called The Trap. “It was kind of a revenge film that took place here,” he said. But he couldn't get the schedules of the actors he wanted—at various times, both Jamie Foxx and Benicio Del Toro were attached to the project—to line up; by the time he could, he'd moved on. “I was feeling differently again. I wanted to laugh.” The Beach Bum, based loosely on a set of characters he was hanging out with in the Keys, was the result. He wrote it swiftly, and then, as he did with Spring Breakers, Korine cast a mix of well-known actors—Jonah Hill, McConaughey, Efron, Lawrence, Fisher—and real-life Florida denizens. “I like when they meet in the middle,” Korine said. “Like when all the secondary characters, and all the locations, all the color, the sky, everything, it affects the main roles in a way. It's almost like a chemical reaction.” And then there are cameos from people like Buffett, who felt the alchemy, too, just walking on the set. “I got to write a song with Snoop Dogg, so that's pretty cool,” Buffett told me.

As a young filmmaker, Korine often talked about how bored he was with conventional Hollywood films. “I didn't want to waste time, like 30 minutes, getting to the good part,” he told me. “I wanted every single thing to be the good part.” He said he wanted the scenes in his own films to feel like they fell from the sky. He still feels that way. “Even in The Beach Bum, I probably cut out 30 or 40 minutes of scenes that I liked. They were good. But I wanted it to only be pure joy, where you can just watch a scene and laugh. That's why I loved Cheech and Chong so much. Because you could just stop and start anywhere, and they're always funny.”

Korine's definition of humor is not the same as most people's. In The Beach Bum, which is cheerful and even wholesome by the standards of Korine's often harsh past work, Moondog and Efron's character tip over a guy's wheelchair and rob him, among other dubiously moral acts. Korine's films, since the very beginning, have been full of people behaving badly in front of an appreciative camera—a world of id, without a superego in sight. Moondog, he said, “lives for the second. There's no self-censor. He's just a sensualist. Whatever feels good, he just acts on it. So he does good, and he does bad.” In Korine's work, those two qualities have often been inseparable. “The essence of comedy is maybe tragedy,” he said. When Korine was growing up, vaudevillians were his heroes. “Guy slips on a banana peel, smacks himself in the head. W. C. Fields falls down some steps. Buster Keaton robs the bank teller. It's a comedy. It's a heightened reality. It's not really real, in a way.”

Korine was so impatient when he was a young filmmaker that his movies would be full of scenes that only distantly related to one another, so powerful was his urge to always see something new or exciting. He's not much more patient now, but he is more interested in narrative and plot than he used to be, so he now films his movies three or four times—he'll shoot the same scene over and over, in different locations. “There's something like 300 locations in the film,” he said. “You almost don't even notice it because they go by so quickly. So, like, the first part of our conversation is here. The next part is in the studio, but it's really all just one scene.” That way, when Korine's boredom kicks in, he can just cut to the same conversation in a different locale. “His methods are about transcending reality,” McConaughey said. “The movie itself feels a little stoned,” Korine said happily. “Not that the visuals are trying to replicate drugs in any way; it's more of just the way smoke kind of goes through—with the edit, with the structure of the film, I wanted it to feel like weed smoke wafting.”

He paused suddenly, out on the concrete deck. “Do you like empanadas?”

I said yes.

“You should try this one,” he said. He pointed to a white box, with a black rubber glove pooled on top of it, which had been resting on the floor since before we got out here. It had been at our feet the whole time, sitting in the dust and the sun.

“I know some Cuban guys, they leave them out here for me,” Korine said. “They put a black glove on the box so people know they're mine.”

He lifted the box off the ground and handed it to me.

Moondog, in The Beach Bum, is an “artist of life,” as Korine described him to me. His talent—in the movie, he wins a great prize for his work—is incidental, even counterproductive, to living that life. “He's not genius in the sense of Mozart or Francis Bacon in that he's tortured by this fire,” Korine said. “He's the opposite. It's like a hassle. You know what I mean? It's a burden. It's like a guy who's born seven foot three. He knows how easy it is to dunk a basketball. Everyone just wants to see him dunk. But he doesn't really want to dunk.”

Korine, of course, could've been describing himself. “Harmony, like Moondog, is ruthless,” McConaughey said. “He demands that the world entertain him. His appetite for destruction makes him a birther of creations. He's inconsiderate, fair-weather, a great liar, will never promise anything, is non-possessive and has no affiliations. He needs controversy. To him, a boring person is a sinner. He needs the world to feed him and he wants to eat. He wants amusement, and will seek out less and less demanding people to be around so to get it. He obviously has the discipline to create art but I'll bet the idea of discipline enrages him.”

When Kids came out, in 1995, Korine was 22, and suddenly famous. But what he did with that fame—the surrealist Letterman appearances, the rejection of the Hollywood agencies and studios that offered him money and opportunities, the constant building of his own weird mythology—became its own art project. “All I really ever wanted is the same thing I want right now, which is just to be able to make the work away from everything,” Korine told me. “And put it out there, then go back and get to enjoy life. I mean, that really is success. I never really craved that other kind that the people seem to be obsessed with. Like now, everyone just photographs everything they eat, and every step, and it just boggles my mind. Because I remember, like, when you're young, you're kind of just sleeping on rooftops and dancing in the shadows. You might forget to call your parents for a week or two at a time. But it's the most beautiful thing, you know? Someone's always like, ‘What movie are you watching?’ ‘What series do you watch?’ I don't watch any of them, but I'll watch the sunset.”

Much of the substance of those days in Korine's life is lost now, by design. “Listen, I feel like I lived a lot of different lives,” Korine said, after I asked a few too many questions about his past. “If I look back on things, I feel like, ‘Wow, that was a lifetime ago.’ Like, another person. But the same person. You know what I mean? It's all a simulation.” He giggled. “At some point, you're like, ‘Is this all real?’ It's like the Berenstein Bears. You know, that whole thing with the bears. The Berenstein Bears never existed.”

Every time he said “Berenstein,” he said it like this: Beren-STEIN.

“There's no such thing as the Berenstein Bears. If you go back now and you look, the books are called the Beren-STAIN Bears. When I first learned that, I was like, ‘How can that be?’ Check your phone.”

I believe you.

“Because nobody's ever heard of the Beren-STAIN Bears. If it was Berenstain, you would know, because the word “stain” would stick in your mind. So why is it now, all of a sudden, Berenstain? There's no record, there's no record ever, of Beren-STEIN. Don't you think there could be a glitch in time or something? I remember the Berenstein Bears. But Berenstein Bears never existed. It was the Beren-STAIN Bears. And once you accept that, how could that not deeply fuck you up?”

Help me understand how that connects to you.

“What I'm trying to say is, it could just be all a simulation.”

Korine started tap-dancing, loudly, in his baseball cleats. He held up his phone, to show me the spelling.

“Berenstain Bears. STAIN.”

So your point is basically that certain facts survive, and they're half true, and that's okay?

“No, I think they're almost all true. But then again, I don't know. It's more like a glitch. Like a glitch in time.”

But these things in your life we're talking about, some of them really happened!

He laughed. “That's true,” he said. But even he can be hazy on the details. There is an independent movie theater next to his studio, here on the second floor of the mall—Korine is good friends with the owner. Last year, the theater screened a print of Gummo. Korine showed up to watch, he said, “because I hadn't seen it in 15 years. And then somewhere in the middle of the movie, I'd forgotten the structure. I thought the projectionist put the reels on wrong. And then he was like, ‘No. This is the way you made it.’ ”

Recently, he told me, he'd also re-discovered a clip from his lost film, Fight Harm. A few months ago, at a film festival in Key West, he'd even shown an audience some of it: a short sequence of him wandering New York at the end of the past century, assaulting random passersby. “I didn't show the whole thing, but I put it up on my phone”—in part just to prove it really existed.

But you lost most of that footage, right?

“Yeah, our house burned down.”

And that's the Connecticut one or the New York one?

“Uh, Connecticut.”

How do you have not one but two fires happen to you?

“The Berenstain Bears, dude. What are you asking me?”

I'm trying to figure out how you were living, that it became possible for a fire to burn down not one but two places that you resided in.

“What do you want to know? Listen. I don't know. To be honest with you, I had another house fire, in Nashville.”

Do you ever ask yourself, “Why does this keep happening?”

“Listen. I have this thing where electronics always break when I touch them. I've had it since I was a kid. If I touch, like, a television remote control a couple of times, it breaks. If I use a blender, it just frizzes out. I mean, the last one, in Nashville, we weren't even there. I wasn't even in the state. And, uh, a bolt of lightning struck, uh, struck a power cord that went into the basement. And the house burned.”

Burned down or just burned?

“Uh, partial.”

Partial.

“Yeah.”

Is this story true?

“One hundred percent.”

You understand why I have to ask?

“No, I don't.”

I feel like you do.

“Why?”

Because there was a time in your life where you'd tell someone like me, “I joined a tribe in Panama.”

“Yeah. But why isn't that true? The Malingerers, yeah. But that was definitely—I would almost guarantee that they're still there.” Korine grinned and threw his cigar end back down onto the deck. “Maybe under a different name, though.”

“I love when the culture takes something, and flips it, and makes it their own.”

Abruptly, he headed for the door to go inside again. “Do you like Sinbad?” he asked. He said he'd been watching the comic's specials at the theater here, next to his studio. Korine walked in and asked his friend if he could cue up one of the Sinbad routines for us. The theater was dark and neon, a warren of different rooms filled with flickering screens. After a couple of moments, the projectionist put it on in the main theater—the room filled with the blaring sound and sight of Sinbad impersonating James Brown, from Sinbad's 1996 Summer Jam music-and-comedy special. Korine slid across the floor at the front of the theater in his cleats and started dancing. He picked up a giant stuffed owl off a couch and shook it rhythmically at the screen. “He's so good!” Korine yelled, over the noise. “Sinbad's so good!”

At some point, Korine realized his wallet was missing. Also his house keys. He called his wife. “She doesn't have it,” he said, hanging up. He didn't seem particularly bothered. When Korine was younger, he said, he was often angry, or frustrated—he felt the urgency of hollowing out a space for himself that didn't yet exist. “I was trying to create my own world at the time, or define what I was trying to do,” he said. Now, he said, “I feel okay.” His movies, strange and idiosyncratic as they have been over the years, have sunk deep into the fabric of pop culture—sometimes, by design, as with Spring Breakers, a film he made “to infiltrate this kind of layer of pop,” as he told me, and sometimes by accident. In 2017, he watched with great amusement as the then 21-year-old rapper Tekashi 6ix9ine had a hit single called “Gummo,” inspired by the movie Korine wrote and directed when 6ix9ine was one year old. “Now if you type ‘Gummo’ into the computer, it comes up as his song,” Korine said. “But that's great. I love when the culture takes something, and flips it, and makes it their own.”

The Beach Bum—dense with Hollywood stars, dreamy in Korine's increasingly charismatic style, and funny in unexpected and surprising ways—feels likely to become another pop touchstone. Korine's dreams and nightmares are as idiosyncratic as ever, but they are supercharged by the presence of actors like McConaughey and Lawrence, pop totems in their own right. Korine said he felt simultaneously happy about the prospect of audiences discovering and delving into The Beach Bum—“definitely you want the movies to affect the culture in some way”—and a little disconnected from it: “If you're like, ‘What do you want to do next?’ I really just want to wake up. Every day I wake up and I'm just happy. I walk out and there's palm trees outside. It's so nice. I'm just like, ‘Thank you!’ ”

He changed out of his cleats, into regular blue Vans, to walk me out. He asked if I wanted to take any books with me from his studio. From a shelf, he pulled the catalog from a 2017 career retrospective he'd had at the Centre Pompidou, in Paris. That had felt good, he said, to see everything he'd ever made in one place—not just the movies but the zines and the paintings and the photographs, all there together. “It's just that it's all about everything,” he said. “It's about the films. It's about the writings, about the work. It's an accumulation. And then at the same time, like…whatever. What does it matter? Like…what?”

Zach Baron is GQ's staff writer.

PRODUCTION CREDITS:

Photographs by Bruce Gilden

Grooming by Daniel Pazos at Creative Management