'Happiest Season' Isn't Perfect, But It's a Start

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The romantic comedy is a genre that has persevered and thrived on formula and escapism. Meet, Lose, Get is a sturdy structure that allows for endless improvisation without any risk of an unhappy ending. This is what we’re seeking when we watch such a film—a comfort as reliable as a favorite blanket. The only way to make a rom-com any more bound to convention is to put the word Christmas in front of it.

Happiest Season, Clea DuVall’s new addition to the holiday rom-com canon, is a classic of the form, abiding by its every time-honored tradition—except one. Our star-crossed lovers are two women: Abby (Kristen Stewart) and Harper (Mackenzie Davis). It may be hard to believe in 2020, but had this film enjoyed its intended pre-COVID theatrical release, it would have been the first big-budget queer Christmas rom-com from any major studio. I have literally waited my entire queer adult life for this moment. I was terrified the movie would suck.

It isn’t easy to surprise and delight an audience when they know exactly what to expect. So the fact that Happiest Season doesn’t suck in the least—that it’s genuinely funny, smart, and heartwarming—is that much more of a marvel.

And yet, I can already hear myself defending the film’s merits to the queer community—the very people I imagine DuVall had in mind when creating it. Because while Happiest Season is great fun, it’s also unabashedly mainstream and flagrantly apolitical. Can a film billed as queer in 2020 get away with that without drawing fire? I’m thinking not.

The unfortunate plight of anyone who makes commercial art for a fractured and marginalized community is that our creations are expected to somehow be all things to all people within that community. I’ve been grappling with this conundrum for some time. When I wrote my last novel, a queer romantic comedy, I made the conscious decision to opt for accessibility over radicalization. I felt that a celebratory queer love story about two women, one that’s free from tragedy, is in its own way radical. That the book would be a major release from a big publisher, intended for wide mainstream consumption, was part of its subversive magic. “Sure, I could write a way queerer story,” I told myself—one that more directly applies my background in gender and sexuality studies, and reflects my awareness of the complexities and intersectionality of gender, race, and class—but the challenge I’d set for myself was to reach an audience that had perhaps never before rooted for two women in love to achieve their happy ending.

With all these clear intentions, wouldn’t you know I’ve still had sleepless nights wondering if I should have pushed further, if I could have done more. That’s what happens when you’re a member of a marginalized community. That’s what it means to not be the default. If you’re in some way a marked identity, you feel responsible for upholding the mantle of that identity. You make the thing you want to make, and then you have to ask, what more could it have done?

There’s a lot that Happiest Season doesn’t do. It is, for the most part, a movie about rich white people and their rich white people problems. Harper’s father is running for mayor in Pennsylvania, but it is only implied, never directly stated, that he leans conservative and Republican. Harper’s sister Sloane is married to Eric, a Black man. Together, they have mixed-race twins—an interesting twist considering this family’s political and cultural inclinations toward the old-fashioned and their obsession with socially acceptable appearances. But the only parental misgivings offered up regarding Sloane and Eric is that they gave up their lucrative careers to start a gift basket business. The film’s gender and sexuality presentation is as vanilla as a White Christmas Frappuccino.

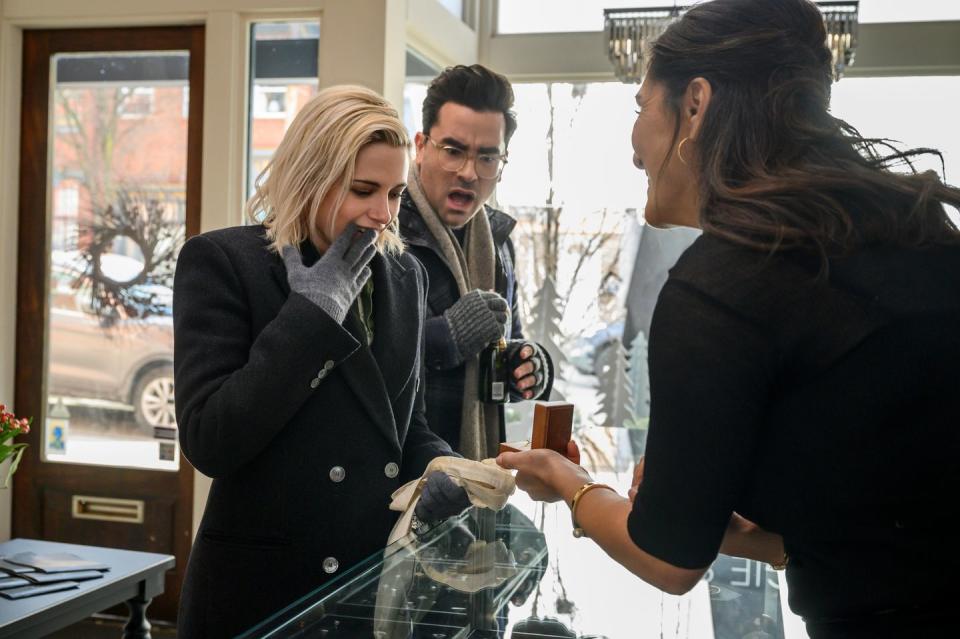

There’s no doubt in my mind, however, that all of this is by design. If you watch the film with an eye toward the subversive, you’ll find knowing winks throughout. Dan Levy’s John serves as a veritable one-man Greek chorus of feminist opposition to the otherwise “Gays: We’re just like straights” angle the main characters uphold.

When Abby tells John that she wants to propose to Harper, he asks why she would want to ruin their perfect relationship “by engaging in one of most archaic institutions in the history of the human race.” He goes on to say that by wanting to marry Harper, what Abby is actually doing is “tricking the woman you claim to love by trapping her in a box of heteronormativity and trying to make her your property.”

Later, John inquires more about Abby’s plan to propose. “I understand that this is very old-fashioned,” Abby says, “but I’m probably going to ask her dad for his blessing and propose on Christmas morning.”

John’s retort? “Way to stick it to the patriarchy. Really well done.”

You can’t tell me this line wouldn’t have gotten the biggest laugh in the theater. You also can’t convince me this entire scene isn’t DuVall’s cheeky way of reminding her audience that if called upon to give a critical analysis of her own film, she damn well could. It’s almost as if she could hear the haters coming for her before the movie even dropped.

It isn’t necessarily a bad thing that the loudest voices tend to be the most radical—in fact, I’d argue that it’s a good thing. But it can be a burden to hear those voices in the back of your mind when you’re trying to create something both artistic and popular, with socially conscious intentions as well as commercial viability.

If we judge DuVall’s direction as we would any straight white male director of note, the question we would be asking is, did she manifest her intentions with this film? The answer to that is a resounding yes.

Nearing Happiest Season’s resolution, Abby and John talk about their dissimilar coming-out experiences with their own parents. “Everybody’s story is different,” John says. “There’s your version, and my version, and everything in between.” The inference here is that no matter where the story of one’s own queerness falls on the spectrum—from catastrophic to fortunate—it’s valid.

Rich white girls have families to come out to also, and often those families are conservative and obsessed with retrograde appearances—even now in 2020. Beneath its glistening wrapping paper and shimmery bow, that’s what this movie is about. It was never intended to be anything else. But we can’t have a spectrum of this type of film if there’s only one of its kind. So who’s going to push the boundaries and make the next queer Christmas rom-com now that the path has been forged?

You Might Also Like