What Happens if the 2020 Election Is Contested? It Wouldn't Be the First Time.

The 2020 United States presidential election is shaping up to be one of the messiest and most unusual political contests in modern memory—with shouting-match debates, historic turnout for early voting, and a Supreme Court confirmation just eight days before the election. No one can say for sure when the country will have a clear winner and, more important, what will happen if either one of the candidates does not accept the results.

Fortunately, history can offer some guidance about how events may shake out in the coming days. The country has seen several disputed presidential elections, some of which ended up being decided on the floor of the House of Representatives while others went to the highest court in the land.

Here's everything you need to know about the strange history of contested—and contentious—elections in the United States

The election of 1800 ended in a tie and the House had to vote 36 times to decide it.

In the election of 1800, Thomas Jefferson and Aaron Burr each received 73 electoral votes. In the event of a tie in the Electoral College, the Constitution leaves it to the House of Representatives to decide. Each state delegation gets a single vote in a so-called “contingent election.” When this voting commenced in February 1801, there were sixteen states, each with one vote, and an absolute majority of nine was required to win. But neither Jefferson nor Burr could eke out a clear victory—the House members voted an astonishing 35 times over a week, unable to declare a winner.

Finally, on the 36th ballot, Jefferson won 10 states and became president. Ironically, Constitutional rules at the time dictated that Burr, as the runner-up, would become vice president. This admittedly messy system led to the ratification of the 12th Amendment in 1804, which states that electors must cast two separate votes: one for President and the other for Vice President.

But, it's important to note that if there is an Electoral College tie this year, it will go to the House for a vote—that constitutional provision hasn't changed.

There was another Electoral College upset in 1824.

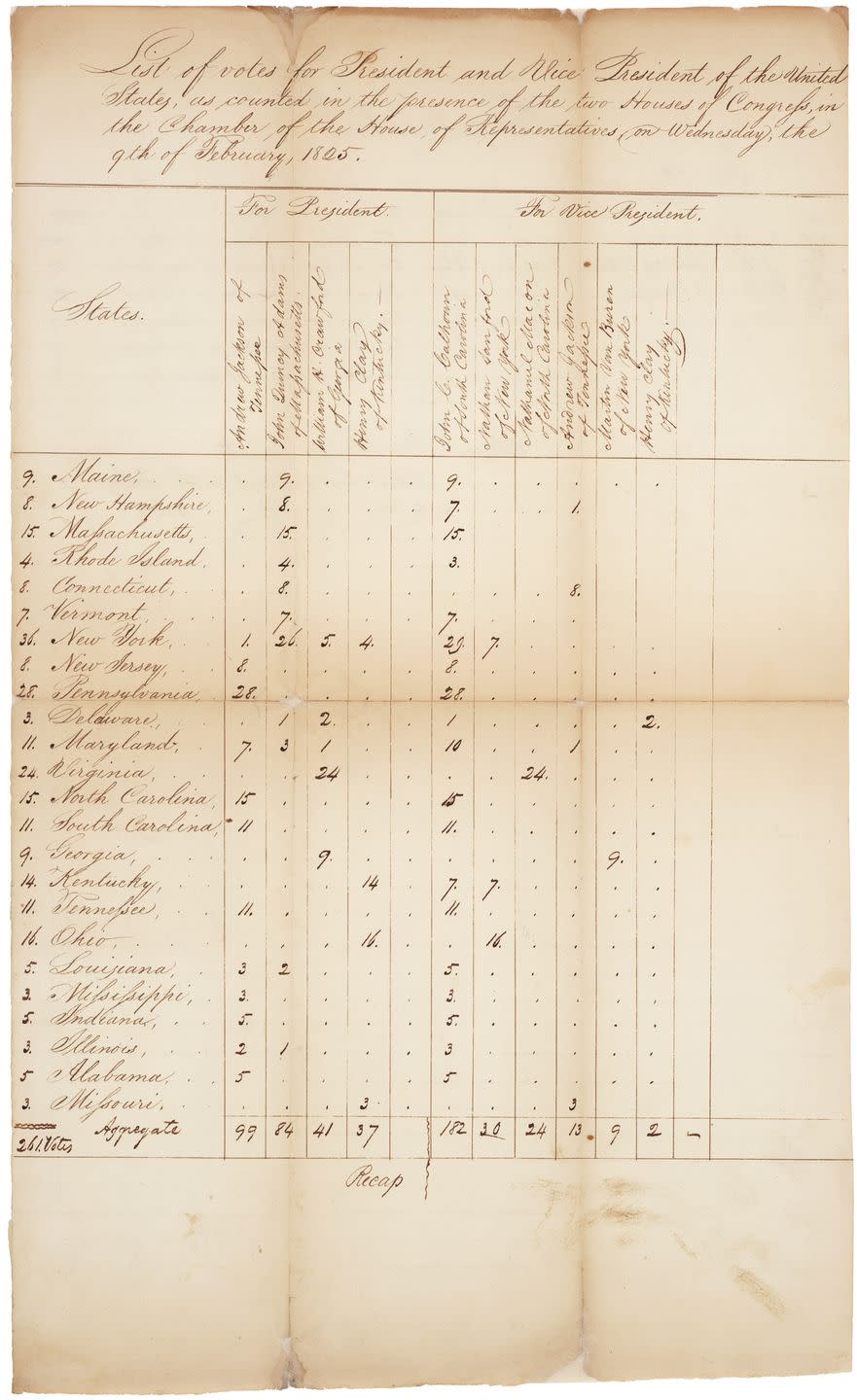

In 1824, Andrew Jackson won the most votes in the Electoral College—as well as the popular vote—in a race with three other presidential candidates (the others were Henry Clay, John Quincy Adams, and William H. Crawford). But Jackson did not receive the majority of 131 electoral votes required to win.

When the vote went to the House, Clay (the Speaker of the House) threw his support to Adams, who emerged victorious in a stunning upset. Jackson (who won the presidency four years later) was furious, believing he should have been the winner and that Clay tampered with the election by supporting Adams.

This was the last time a presidential election went to the House for an up-and-down vote.

The 1876 election was the most contentious in U.S. history.

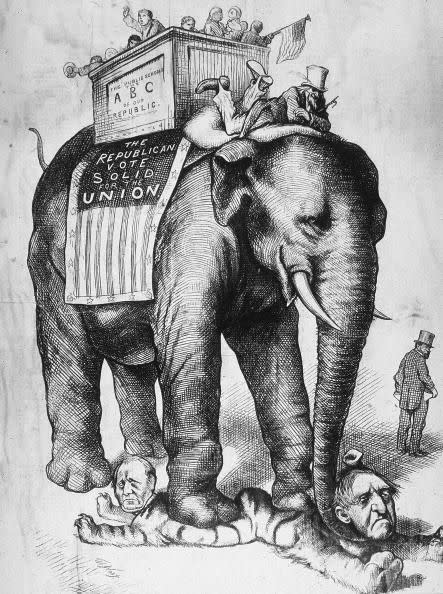

By most accounts, the most controversial presidential election in the U.S. was the 1876 matchup between Republican Rutherford B. Hayes and Democrat Samuel J. Tilden. Although the contest was held a decade after the end of the Civil War and Reconstruction was well underway, the country was still divided by the conflict.

Back then, the demographics of the two major political parties were geographically "flipped" from how we perceive them today: the Republicans were popular mostly in the North in former Union states and among Black voters in the South, while the Democrats were powerful among white voters in the South.

Historians have noted that both Democrats and Republicans committed election fraud, but there was also widespread violence against Black voters in the South and voter intimidation by Democrats.

In the end, Tilden, the Democrat, won the popular vote. Republicans challenged the results in three Southern states—Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina—which had submitted two different sets of returns, showing a different winner, to the Electoral College. Oregon also submitted two sets of returns.

In January 1877, Congress established a bipartisan commission comprising 15 members of Congress (seven Democrats, seven Republicans, and one independent) and the Supreme Court to decide how to allocate the disputed Electoral College returns. There were accusations of chicanery on both sides, but ultimately, in what became known as "The Compromise of 1877," Democrats decided to allow Hayes to become President in exchange for the removal of federal troops from the South and an end to Reconstruction.

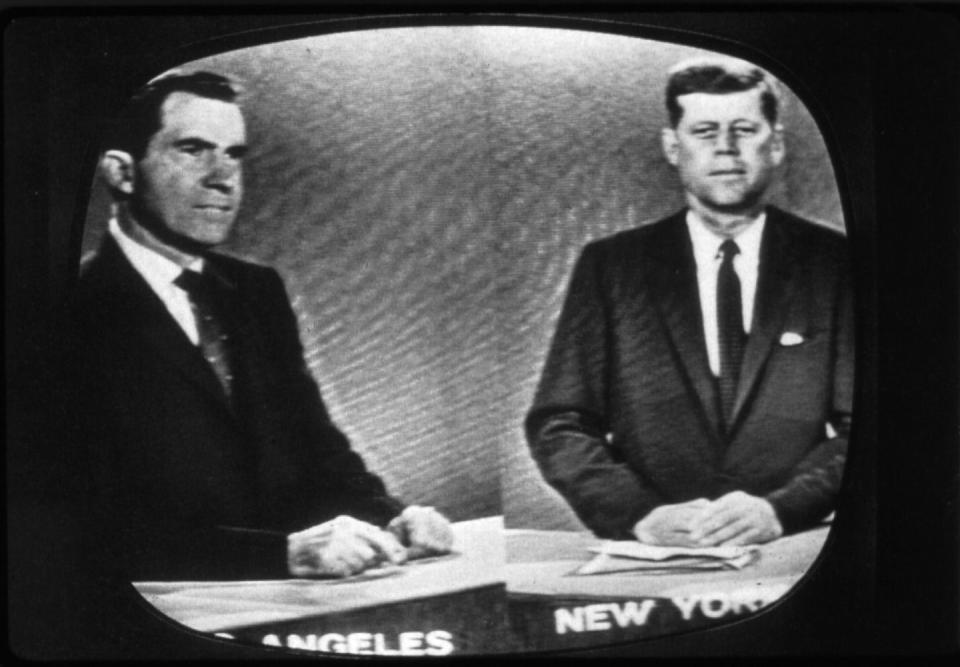

Kennedy's 1960 victory over Nixon is often called the "stolen election."

The 1960 election, which featured the first televised debates, was incredibly close. Nixon, the sitting Vice President, lost the popular vote to Kennedy, then a Massachusetts senator, by 113,000 votes of the 68 million cast—a minuscule margin of 0.2%. While Kennedy captured a seemingly commanding 303 Electoral College votes compared to Nixon's 219, even those numbers were a bit misleading. California, for example, was originally called for Kennedy, but Nixon ended up with the state's 32 electoral votes on November 17 after absentee ballots were tallied. That such a crucial state was so close shows the down-to-the-wire nature of the race.

But there were also accusations that the Kennedy camp had engaged in election tampering. In Illinois, he won by just 8,800 votes, mostly clustered in Chicago, which was run by Mayor Richard J. Daley. The "Democratic Machine" in Chicago was long suspected of interfering in elections, though nothing was ever proven.

And in Texas, home of Kennedy's running mate, Lyndon Johnson—who had been caught up in the "Box 13" scandal in his 1948 U.S. Senate race, when 200 votes for him mysteriously appeared—Kennedy won by only 46,000 votes. Together, Illinois and Texas had 51 electoral votes, and flipping them from Kennedy to Nixon would have handed Nixon the election.

Nixon publicly conceded defeat early in the morning after the election. While Nixon always claimed he had no part in it, his campaign did challenge the results in various ways, with recounts and court cases in Illinois, Texas, and even other states. (Many historians dispute Nixon's "country above party" message, suggesting he surely would have authorized the efforts to challenge Kennedy's win.) The challenges did not succeed and by mid-December, Nixon reportedly privately told friends, "we won, but they stole it from us.”

Who can forget the infamous "hanging chads" of 2000?

The 2000 election between George W. Bush and Al Gore became one of the most memorable—and unusual— in modern history when it all came to down to so-called "hanging chads" and a mere 537 votes in Florida.

On election night, Gore had captured the popular vote, but the results were too close to call in Florida. (Some networks initially called the state, with 25 electoral votes, for Gore, then retracted and called it for Bush.) At one point, Gore called Bush to concede—then in an extraordinary move, called back in a matter of hours to retract his concession.

The next day, it emerged that Bush had won Florida by such a close margin that state law required a recount. Star lawyers from both campaigns descended upon the Sunshine State in what became a month-long series of legal battles. In some counties, there was a dilemma surrounding punch-card ballots where the voter had only succeeded in detaching a portion of the perforated paper, the so-called "hanging chads." Election officials spent days hand-counting ballots, examining the chads to determine the voter's intention.

Ultimately, the fight went all the way to the Supreme Court in the decision Bush v. Gore, which ended the recount. In the end, Bush won Florida by 537 votes, a margin of 0.009%, and this put him over the top to clench victory with 271 Electoral College votes.

We don't know what will happen this year, but contested results are almost a given.

In an election year unlike any other, it's almost certain that one or both candidates will challenge some results in court or that votes—whether mail-in or in-person—will need to be recounted. The country may not even know the results for days, as states have different rules about when mail-in ballots can be opened and counted—some states, like Pennsylvania, do not allow them to be read until election day, November 3, while other states, like Florida, are already processing ballots.

Both Trump’s and Biden’s campaigns have lined up armies of lawyers—and have already gone to court over mail-in ballot deadlines and other voting issues caused by the Covid-19 pandemic.

If there is a tie in the Electoral College, the election will be taken to the House of Representatives for a "contingent election," as happened in 1800 and 1824.

If there are court battles at the state level, they will almost definitely wind their way through the federal appeals process. Given the long shadow of the 2000 court decision, and Amy Coney Barrett's 11th-hour ascension to replace the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, there are plenty of questions about what would happen should issues around this election appear before the Supreme Court.

You Might Also Like